Coronavirus Victoria: ‘Confronting’ scenes at locked-down public housing towers in Melbourne

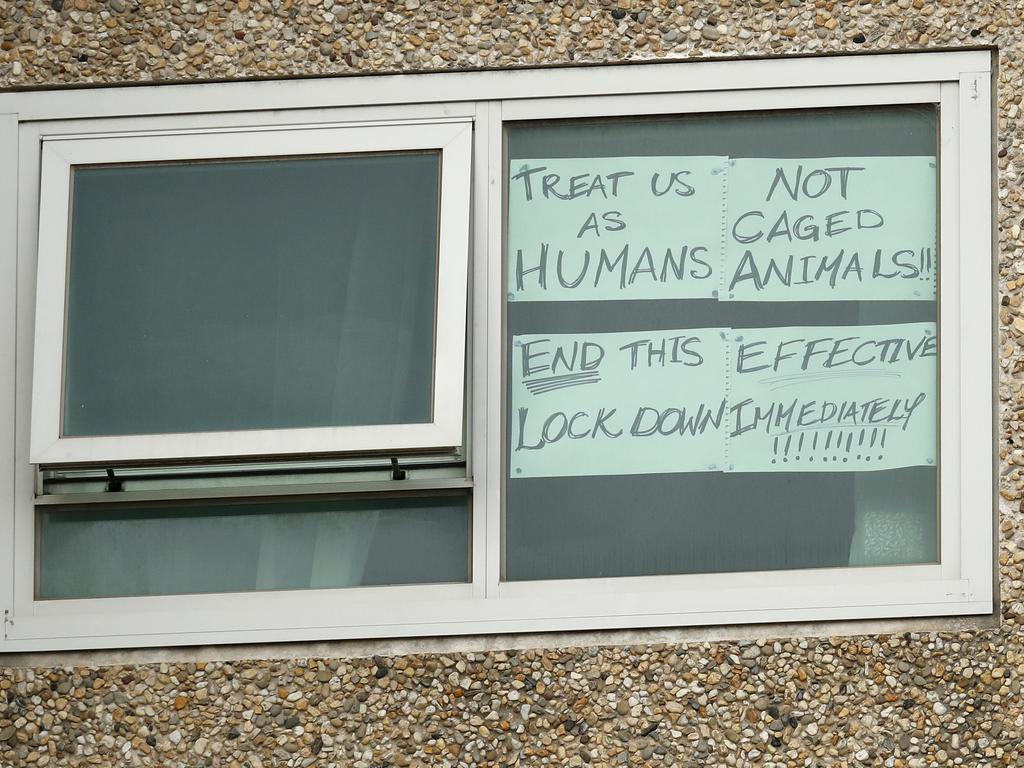

The public health response to COVID-19 outbreaks in Melbourne housing estates looks more like a “crime scene”, and it wouldn’t happen in rich suburbs.

The lockdown of several public housing towers in Melbourne looks more like a devastating crime scene than a public health emergency, a community services leader has said.

On Saturday afternoon, an immediate “hard lockdown” was imposed on nine estates that confined thousands of people to their homes for at least five days in response to a surge in coronavirus cases.

There was no warning, the situation was poorly communicated and a heavy police presence – and absence of health authorities on site – has sparked fear and confusion.

“I was there yesterday and I have to say, it’s very unsettling,” Emma King, chief executive officer of the Victorian Council of Social Services, told news.com.au.

“There’s a very strong police and protective services presence, not just at the estate but in surrounding streets. In a way that’s not normal. It’s pretty confronting.”

The towers house some of Melbourne’s most vulnerable people, comprising struggling families, the elderly, ill and disabled, and migrants.

“This is a public health issue, but it doesn’t look like it,” Ms King said.

“No-one has done anything wrong on the estate, but it looks like a crime scene. The police presence is very strong. I expected a much stronger public health presence on site.”

RELATED: Follow the latest coronavirus updates

Just before speaking to news.com.au on Tuesday morning, Ms King was in a briefing with various community groups to discuss how they can fill the urgent gaps left by the government.

While she understood the need for health authorities to act, she’s baffled why the lockdown was instituted without any notice.

Reports have emerged that residents weren’t told they were being locked inside for the week.

“There are issues with people not having food because they had no notice, then being delivered packages of food with items that have expired, or food that isn’t appropriate – people might be vegetarian, and that sort of thing,” Ms King said.

“One resident was telling us that there was a public broadcast at 10.30pm telling people to come down and get dinner. People had been told not to step foot out of their apartment.”

RELATED: Fears authorities have ‘lost control’ of COVID-19 in Victoria

The apparent double-standards at play in this situation are also “confronting”, she said.

“There are some pretty flash high-rise blocks down the road and I doubt they would go into lockdown (if there was an outbreak). I don’t think it’d be handled in this way.”

Ms King said she lives in an area not far from the estate, in an area that’s currently subjected to a localised lockdown.

But it might as well be a world away by comparison.

“The double standard strikes me quite strongly. We had six hours to go out and get groceries. I can go out for a walk for exercise. We’re told we’re all in this together but it doesn’t feel like it.

“These people are at particular risk already and they’re now locked down in a way that others in the postcode are not.

“I don’t doubt for a second that the intent here is to stop people for dying. The way it’s being managed though … it’s surreal.”

RELATED: Locked-down tower residents denied food packages

There’s mounting evidence that some basic needs haven’t been met and it’s causing fear, uncertainty and tension.

“We’ve heard from people who need care but can’t get it. We’ve heard from people who are carers for others but can’t provide it,” Ms King said.

“There are kids with autism who need to be able to go outside for sensory relief, who benefit from routine, who don’t have that.”

One resident at a tower in Flemington said the immediate lockdown wasn’t communicated and the first she knew of it was hours later, when a group of 20 police officers greeted her at the building’s entrance as she tried to go out.

By Tuesday morning, her household, comprising her, her mother and her two brothers, hadn’t been visited by health or community service authorities.

They were told that someone would come to test them on Monday morning but that never happened.

“The real question is, why were the police not briefed before they were sent in? Because all the police I spoke to when I tried to ask them questions told me they also didn’t know anything, that they were as confused as I was,” she told The Guardian.

Ms King is hopeful that Tuesday will represent a turning point in the response at the affected public housing towers.

“Some community health providers will door knock the estate today, with nurses on site. Testing will occur today. I understand Royal Melbourne Hospital will be on site.

“There will be conversations about what people need and how they’re going generally. It’s a welcome and significant shift in the right direction.

“I think it’s a shame this didn’t happen from the very outset though.”

At the same time, a new case of coronavirus detected in another housing estate in a different suburb now has Ms King worried.

“I really hope that there are lessons learnt from this situation that won’t be repeated,” she said.

And when the COVID-19 crisis is all said and done, Ms King hopes the government will take action on this stark illustration of the public housing crisis that’s plaguing Victoria.

“When you’ve got 100,000 people on a waiting list, that’s more than enough people to fill the MCG, that shows the desperate need for a greater investment in public housing.

“We’re so far behind the national average, to the point where we need at least 6000 new properties a year, every year, for the next decade, just to catch up.”