Writing for Raksmey: A story of Cambodia

NOT every morning, but far too often in her time with Cambodian refugees, Australian nun Joan Healy heard the sound of shelling.

NOT every morning, but far too often in her time on the Thai border camps, Australian nun Joan Healy heard the sound of shelling.

Thousands of people who were seeking refuge from the Khmer Rouge were again in danger.

Some had seen family members killed in front of them. Some had been injured by landmines. All were fearful of their lives.

It was 1989, and the horror of war was all too familiar to the locals.

In 1975 Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge who declared it Year Zero.

Also known as the Communist Party of Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge held the entire population of between seven and eight million people captive. They abolished private ownership and currency, they closed markets and schools and emptied towns.

Purges of “guilty” people were carried out, and in the years following around two million people were killed.

In 1978 the Vietnamese “liberated” the country from Pol Pot, but the Khmer Rouge kept up guerilla warfare from the jungle. Millions who had been held captive by Pol Pot walked the roads looking for food and freedom.

Many searched for lost family members, and many more looked for safety by escaping to camps set up on the Thai border of Cambodia. These camps weren’t safe from the Khmer Rouge, with regular shelling, and community “buildings” burned to the ground.

Sister Joan Healy is an Australian Jesuit nun. In 1989 she moved to one of these camps, known as “Site 2”, and worked with people who had survived the atrocities of war.

An extract of her book, Writing for Raskmey, is below:

The shelling has stopped, the danger has passed, we have permission to return to the camp. The mood of the Cambodians here has changed from fear to mourning. The monks are moving from house to house chanting the traditional chants for the dead. A great many KPNLF soldiers, including many conscripts new and untrained on the battlefield, have died. It seems that the chanting will never stop: it is so loud, so incessant, that conversation is impossible.

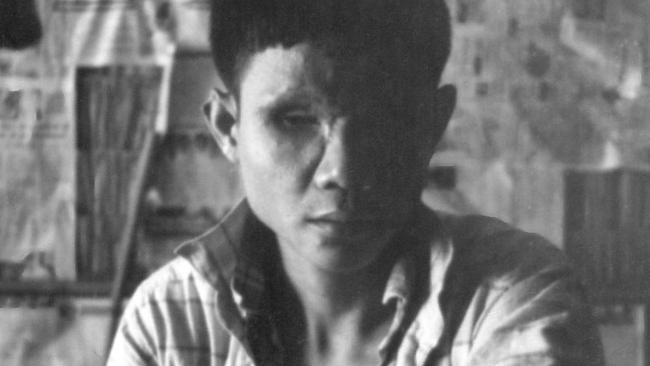

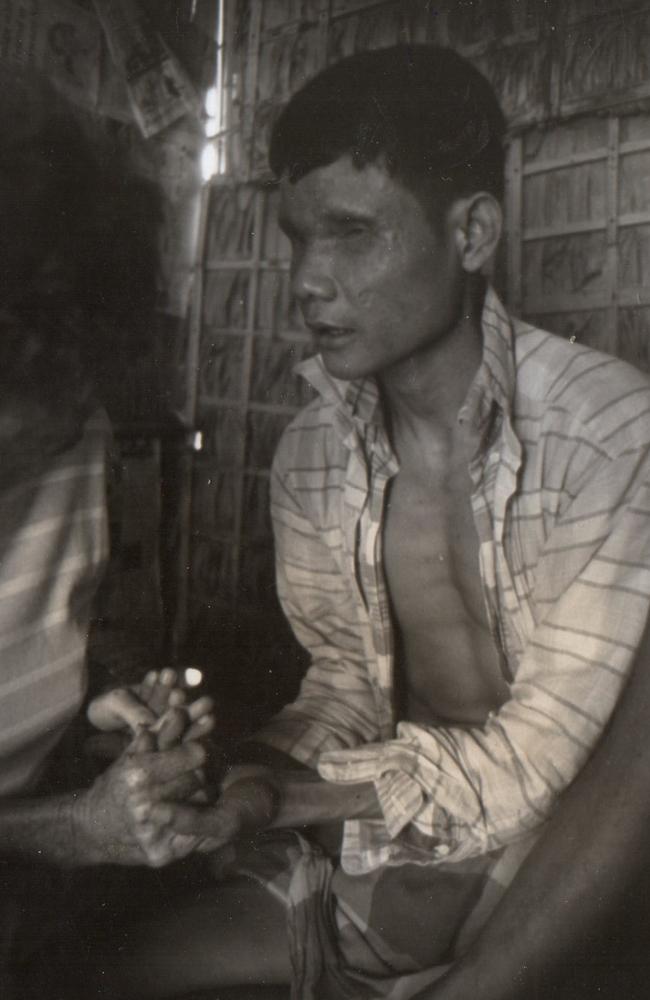

Phaly asks me to sit with a young soldier, Keing, who has been brought to the Centre crazed with anguish. Keing sits on a piece of blue plastic in a darkened corner where a single thread of light comes through a slit in the bamboo wall. His eyelids close across empty sockets. Everything is darkness for him. He is wearing a check flannelette shirt unbuttoned, and underpants. His head is bowed, his shoulders hunched. His bare right leg is flat on the ground in lotus position. His left knee is raised to his chest; he hugs his arms around it so that one hand grasps his ankle. I notice that his fingers are long and tapered, musician’s hands, perhaps, in a different life.

I hear his story. Keing’s father and mother, brother and sisters died in Khmer Rouge times. He honoured his army commander in place of the father he had lost. He did not hesitate when the commander asked him to crawl ahead through a field. A landmine exploded, his limbs were intact but his face and eyes bore the brunt of the flying fragments. In the battlefield tent-clinic the medics removed his eyes. Day after day he waits for the commander. The commander does not come.

Tears flow down Keing’s face from the tear ducts at the edge of his empty eye sockets, he believes that his eyes could have been saved. After many weeks he will feel my face and lips and eyes.

This time I am more sensitive in what I write back to Australia:

Keing, a young man just recently blinded in the war, has become a friend. In his grief he was particularly alone as he has no family members alive ‘after Pol Pot.’ He is strong, handsome, gentle and intelligent but his eye sockets are hollow and empty. One by one I have met his friends and begun to know their capacity to help Keing and to help me … They are loving, challenging, open about their own feelings of anguish as tears stream from Keing’s empty eyes.

In truth it is anguish for anybody to be close to Keing. We look for some way to soften his terrible grief. He is alert to the sound of music. I bring a cassette player and many batteries from Ta Phraya. He listens.

When the shelling around the border ceases, a small village just inside Cambodia is flattened by an attack from the Phnom Penh troops. It is not the usual attack. It is a hail of heavy rockets coming from a Russian multiple-missile launcher, many kilometres distant. Missiles follow each other second by second. This deluge makes a distinctive screaming sound. The weapon is not precisely accurate over the distance. It is designed to terrify the neighbourhood. Ammunition of such sophistication has not been heard in these parts before. Forty people are confirmed dead, though many more are not accounted for.

Two hundred surviving villagers flee to Site 2 for refuge. They are, of course, illegal immigrants here. They are stripped of all their possessions as the bribe for ‘permission to cross’ and are provided with a little rice and water as they huddle miserably in the same pagoda where monks chant day and night lamenting the dead soldiers.

One night a recently married soldier, traumatised by what he has seen and perhaps by what he has done, comes home to the camp, puts his two arms around his wife and pulls the pin on a hand grenade. They both die instantly.

Nee calls me aside. ‘This is hard for you,’ he says. ‘We have been here for nine years already. You get used to it.’

Writing for Raksmey: A Story of Cambodia by Joan Healy is published by Monash University Publishing and will be launched this Sunday, November 13.