‘Region on the brink’: Map exposes China’s ‘menacing’ true mission in South China Sea

Something strange is happening in the South China Sea, and despite Beijing’s promises, it has dire consequences for the region and beyond.

President Putin may have become the unwitting meat in a South China Sea sandwich.

His cash-strapped oil company is drilling there for Vietnam. But Beijing’s getting pushy.

Chinese Coast Guard vessels have been harassing the Russian-owned oil rig near Vanguard Bank, part of the South China Sea just off the coast of Vietnam.

It’s been there since June.

It’s been contracted by Hanoi.

Now it could be the first significant test of the “bromance” between President Putin and Chairman Xi.

Vietnamese Foreign Minister Pham Binh Minh has warned the United Nations that “unilateral action” in the South China Sea risks escalating already high tensions.

“Vietnam has on many occasions voiced its concerns over the recent complicated developments in the South China Sea, including serious incidents that infringed upon Vietnam’s sovereignty,” Mr Pham said at the weekend.

On December 20, satellite imagery recorded 95 Chinese boats without fishing gear surrounding the Philippines' Thitu Island.

— CSIS (@CSIS) September 29, 2019

Learn how China uses maritime militias to assert its claim over the South China Sea: https://t.co/yvL2DpjpDF pic.twitter.com/GIHxhAuKm2

He avoided mentioning Beijing by name.

But everybody knew who he was talking about.

“Relevant states should exercise restraint and refrain from conducting unilateral acts, which might complicate or escalate tensions at sea, and settle disputes by peaceful means,” Mr Pham warned.

But China has already made its stance clear. For months now it has been violating Vietnam’s UN-recognised economic zone with its military-controlled coast guard vessels under the guise of a seabed survey.

In reality, they’ve been menacing Vietnamese-Russian gas drilling operations.

Now, with tensions rapidly approaching flashpoint between the neighbouring Communist countries, Moscow finds itself in a precarious position.

RUSSIAN ROULETTE

Moscow and Beijing have been making a great display of improving their economic, political and military ties in recent years. The two authoritarian states appear to have found succour and support in each other in the face of international sanctions and a trade “war” with the United States.

The plan is to double trade between the two countries over the next five years, with new joint projects in energy, agriculture and industry.

China’s Chairman Xi even declared Mr Putin to be his “best friend” during a visit to Russia earlier this year. The two leaders signed statements committing to “the development of strategic co-operation and comprehensive partnership”, as well as “strengthening strategic stability … (including) international issues of mutual interest, as well as issues of global strategic stability.”

So, where is this budding “bromance” headed?

It’s complicated, analysts say.

Especially those last two points.

Mutual interest and strategic stability.

With up to 20 armed vessels from both Vietnam and China ploughing the waters around its gas rig, Moscow may soon find itself forced to choose sides.

Mr Putin’s stance on the standoff is unclear.

Russian state-controlled media is silent on the matter.

Meanwhile, the Russian-owned oil rig sits in the middle of an increasingly tense international powerplay.

“(Beijing) seems to be wagering that if it can maintain a semipermanent (coast guard) presence for long enough, regional states will eventually accede to its de facto control of those areas,” an international think tank warns.

VIETNAM RESISTS

Hanoi shares a significant border with China. And it’s a border the two Communist nations have already clashed over.

China invaded in 1979, shortly after Vietnam occupied Cambodia. In the short war, Beijing’s forces were rapidly expelled from Hanoi’s territory — though both nations claimed victory.

Now, however, Beijing prefers to act as though the conflict never happened.

But $US2.5 trillion worth of oil and gas has the two nations at odds once again.

A large swath of the South China Sea is recognised as belonging to neighbouring Vietnam under international laws established after World War II. China, which sits on the northern territorial limits of the sea, unilaterally disagrees. It claims the entire waterway as its own under a somewhat vague “Nine-Dash Line” delineation — up to the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan.

This claim was thrown out by an international court of arbitration in 2016.

Now Vietnam says China is “intimidating” it by sending its supposedly civilian coast guard vessels to block exploration operations on its continental shelf. But there’s a complication: the rig is owned by Russia’s Rosneft Oil PJSC company.

Looks like Haiyang Dizhi 8 is heading toward home. Will have to wait for some more hours to see if it really ends the unauthorised survey in Vietnam's EEZ which has lasted for nearly 3 months. pic.twitter.com/dR2KFDWSvA

— South China Sea News (@SCS_news) September 28, 2019

Vietnam says the interference has so far cost the operation some $295 million.

On the sidelines of a recent ASEAN meeting, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo joined Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne in expressing concern about “credible reports of disruptive activities in relation to longstanding oil and gas projects in the South China Sea”.

But tensions seem set to only increase.

Still, the tension remains in the area of block 06.1 with the new presence of Haijing 37111 and 31302. Haijing 45111 is at anchor near Prince of Wales Bank. https://t.co/qQQAkTPFw1 pic.twitter.com/PZs8adqUnP

— South China Sea News (@SCS_news) September 28, 2019

The new standoff comes amid talks between China and the Philippines for “joint” energy exploration activities and moves towards similar discussions with Malaysia.

Beijing’s looming presence has Hanoi worried.

“The South China Sea has important implications for countries inside and outside the region in terms of economy, security, safety, freedom of aviation and navigation,” Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Le Thi Thu Hang said. “Vietnam welcomes and is willing to join other nations and the international community” to maintain peace, stability and security in the region”.

Mr Putin, however, has remained silent on the matter.

‘MY ENEMY’S ENEMY IS MY FRIEND’

Russia’s military is again making its presence known in the Pacific Ocean. Recently, its strategic bombers joined those of China in a provocative “probe” of an island jointly claimed by Japan and South Korea. It sparked an international incident and a collapse in diplomatic ties between the two vital Western allies.

In September, China joined India and Pakistan in Russia’s massive “Tsentr 2019” war games. It was just the second time it had sent forces to take part. Russia has also been sending its ships and warplanes to participate in Chinese exercises in the disputed east and south China seas.

“There’s a growing consensus that a partnership between Russia and China is quite a powerful force, led by China rather than Russia, but that between the two of them they could represent quite a powerful bloc,” Cailin Birch, global economist at the Economist Intelligence Unit, told CNBC.

“Russia would be the junior partner based on the size of markets and its prospect for growth, so obviously in that sense, Russia would be pulled into China’s sway slightly.”

But the petrochemical drilling company Rosneft is majority-owned by Moscow.

Russia has officially held a neutral position over the ownership of the South China Sea, as has the United States. Both purport to maintain the status quo and freedom of access and trade.

But Moscow has been supporting Beijing’s stance that any nation not bordering the sea should keep out of the dispute. The Kremlin also loudly agrees with the Chinese Communist Party line that attempts to portray the territorial dispute as a matter of international significance is a “cynical” expression of US “imperialism”.

And Mr Putin has said he is “solidarising with and supporting China’s stance” in rejecting the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s 2016 ruling against the nine-dash line.

But while Russia’s diplomatic stance may be supporting China, its actions are not.

Rosneft is just one of several Russian companies operating in Vietnamese waters.

Meanwhile, China’s coast guard and maritime militia is harassing fishers, military vessels and commercial operations throughout the South China Sea.

Neither Beijing nor Moscow want to draw attention to what could be seen as an affront to the other’s interests.

And Mr Putin is happy to let Beijing’s ambitions play out in the South China Sea — as long as its interests aren’t affected.

CREEPING EXPANSION

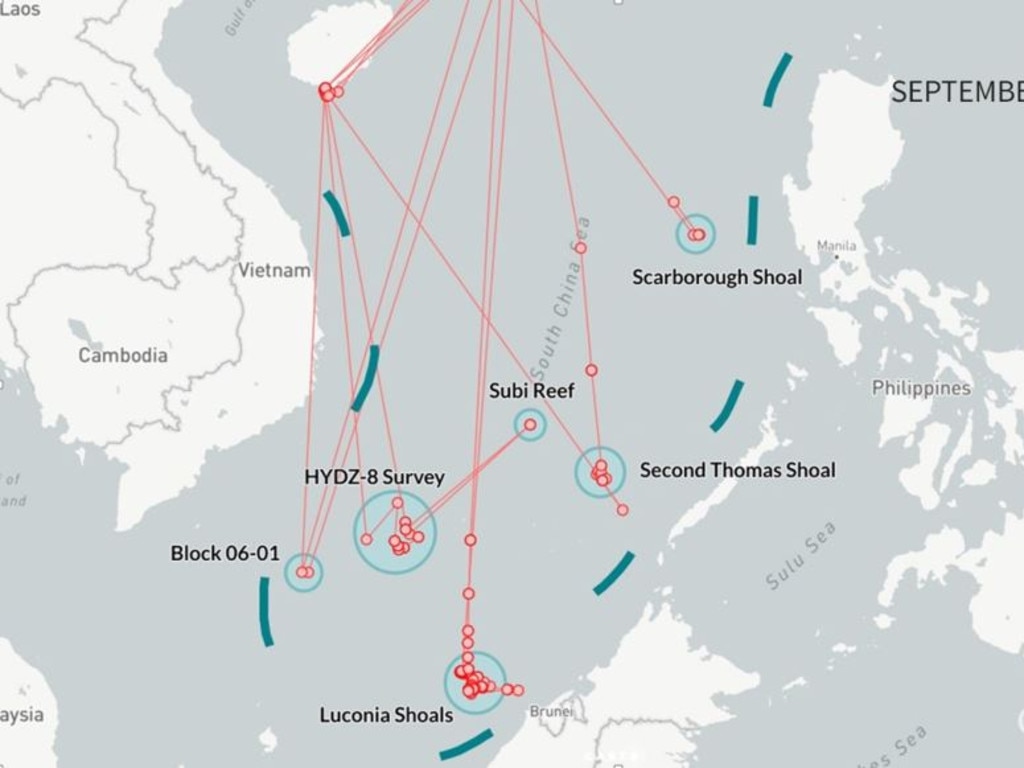

China’s controversial artificial island fortresses are playing a pivotal role in its intimidation tactics, says the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI).

It points out the military-controlled Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) has been able to extend Beijing’s territorial claims through its “access to newly built port facilities on artificial islands in the Spratlys”.

“(This) allows it to sustain such deployments. But less appreciated is the persistent presence the CCG maintains around several symbolically important features in the South China Sea: Luconia Shoals, Second Thomas Shoal, and Scarborough Shoal.”

These shoals are far from the Chinese mainland and Hainan Island. They are deep within boundaries ascribed by the UN to Vietnam, Malaysia and Philippine ownership.

But the AMTI report states it has identified 14 CCG vessels active in those disputed waters in the past year.

“What really sets the vessels patrolling Luconia, Second Thomas and Scarborough apart is that it appears they want to be seen,” the report reads. “This patrol pattern highlights an important CCG objective in the South China Sea — to create a routine, highly visible Chinese presence at key sites over which Beijing claims sovereignty.”

Meanwhile, Beijing is set for a further escalation with Hanoi.

A large crane ship has been spotted some 90km off Vietnam’s coast, well within its 370km exclusive economic zone. Named Lan Jing, its job is to install oil and gas rigs. For Beijing.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer @JamieSeidel