North Korea’s ‘body sites’: Rogue state kills citizens for watching foreign TV, report says

A NEW report has revealed in stone cold detail how the notoriously secretive Kim Jong-un disposes of people he doesn’t want.

LITTLE is known about what really goes on there, but a new report into North Korea’s practice of executing accused criminals has revealed in chilling detail how the regime disposes of undesirables.

Kim Jong-un’s hermit state carries out executions in public places including schoolyards and markets as a way of instilling fear in its people, according to Seoul-based human rights group the Transitional Justice Working Group.

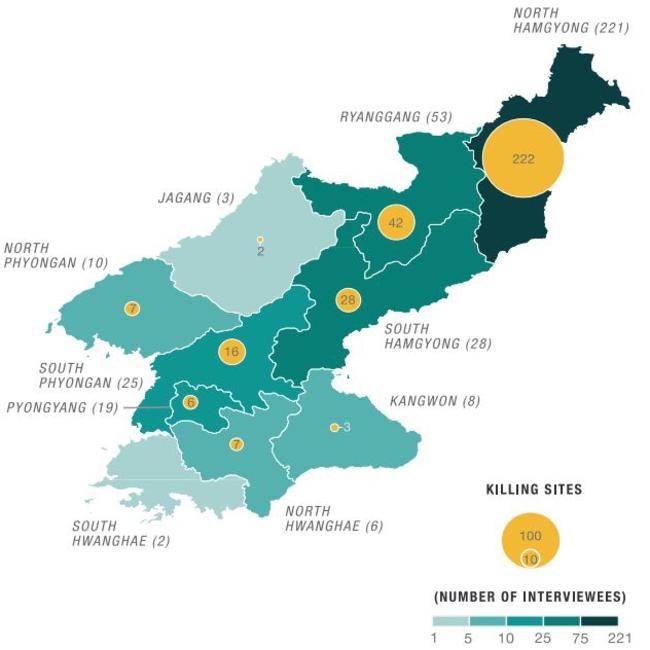

Based on interviews with 375 North Korean defectors over two years, the report documents for the first time the locations of public killings and mass burials to create a “digital map of crimes against humanity in North Korea.”

“The maps and the accompanying testimonies create a picture of the scale of the abuses that have taken place over decades,” the Seoul-based NGO says.

The report claims to reveal 47 “body sites” including mass graves and cremation sites as well as those used to kill people accused of “crimes” as innocuous as watching foreign TV.

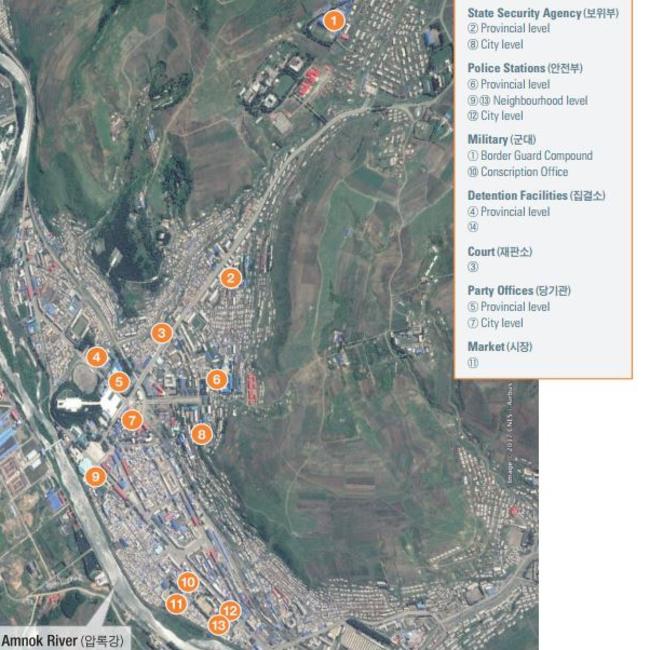

“In ordinary areas outside the prison system, our interviewees stated that public executions take place near river banks, in river beds, near bridges, in public sports stadiums, in the local marketplace, on school grounds in the fringes of the city, or on mountainsides,” the report reveals.

According to testimonies, the method of execution also included beating people to death, with one interviewee revealing: “Some crimes were considered not worth wasting bullets on.”

“Many interviewees said that the final decision for a public execution was often influenced by individuals having a ‘bad’ family background in addition to the crime they were alleged to have committed,” the report states.

It goes on to detail how executions are carried out publicly to create an “atmosphere of fear” and used as a “deterrence tactic”.

DEATH MAPS

North Korean participants identified 47 possible “body sites”, including cremation sites and crude burials in remote areas.

The report revealed how these sites are often close to detention facilities and labour camps with some graves believed to contain up to 15 bodies each.

The majority of burial and killing sites identified were in North Hamgyong Province, which borders China.

In political prison camps (called “gwalliso”) and correctional prisons (“gyohwaso”) executions are reportedly used as punishment for attempting to escape.

“In the gwalliso, executions were described by interviewees as taking two forms: either informal — meaning they are undertaken in secret away from the view of other inmates; or formal — where other inmates are required to watch the proceedings,” the report states.

While earlier methods of execution included hanging, shooting remains the most common way for the state to kill people in North Korea today.

The greatest number of executions were carried out between 1994 and 2000, when food shortages were at their most severe.

It was in one such prison camp that American tourist Otto Warmbier came to suffer a catastrophic and ultimately fatal neurological injury that baffled doctors when he was handed back to his family in June.

Beatings, rape and starvation are common methods used to control prisoners in camps, though Warmbier showed no sign of having suffered extreme violence before his death.

‘REAL ABUSER’

North Korea categorically rejects charges of human rights abuses, saying its citizens enjoy protection under the constitution.

It has also repeatedly accused the United States of being the world’s worst rights violator.

The secretive regime was last year dubbed the most “repressive in the world” by Human Rights Watch, which has accused the government of holding public executions “to generate fearful obedience”.

According to Reuters, UN member countries urged the Security Council in 2014 to consider referring North Korea and its leader to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity, as alleged in a Commission of Inquiry report.

— with Reuters