Last hours on Death Island; Bali Nine’s final moments before firing squad

DETAILS of Bali Nine kingpins’ final hours after signing their death warrants have been revealed in a harrowing new book about their execution.

DETAILS of Bali Nine kingpins’ final hours after signing their death warrants have been revealed in a harrowing new book about their execution.

2.50pm, Anzac Day, 2015, Besi Prison Nusakambangan Island, Java, Indonesia:

MYURAN Sukumaran had just refused to sign his own death warrant.

There was a stunned silence inside Besi prison.

No other prisoner transported to so-called “Death Island” to be shot by firing squad before Sukumaran had ever refused to sign his or her execution warrant.

As soon as he did, he had 72 hours left alive.

The 34-year-old and his Bali Nine cohort Andrew Chan had been brought to the stark confines of Besi seven weeks earlier as condemned men.

Handcuffed, bundled into a Barracuda tank at dawn they had left Kerobokan jail in Bali, a six star resort by comparison, on the last flight they would ever take.

At Besi, the two Australians shared a stifling five-by-six metre caged cell where they were being “readied for death”.

As journalist and author Cindy Wockner reveals in her fascinating but intense account of the Bali Nine kingpins last days on earth, leaving Kerobokan for isolated Nusakambangan had stunned the two Australians.

TERROR ON DEATH ISLAND

“For the first time in a decade, they were completely shut off from the outside world,” Wockner writes.

“They had nothing. Andrew and Myuran were terrified.”

Wockner, an Indonesia specialist since she first went there to report on the 2002 Bali bombing which killed 88 Australians, had covered drug arrests from Schapelle Corby, to the Bali Nine and many Australians thereafter.

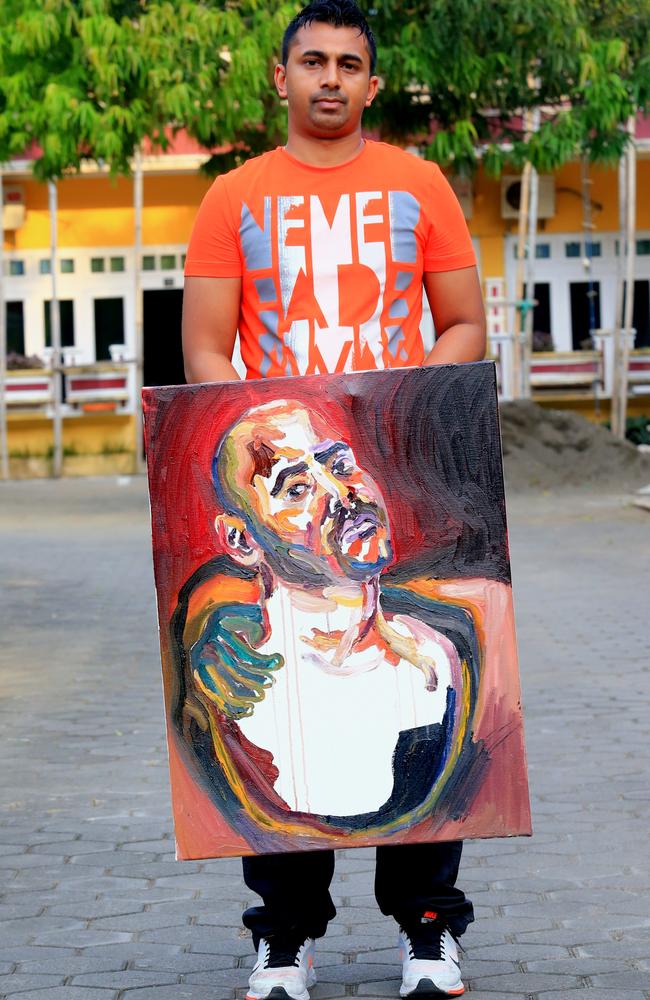

In The Pastor and The Painter she recounts Chan and Sukumaran’s decade behind bars in Bali and their final journey to their death on a floodlit field behind a Nusakambangan police station.

Only five months earlier when their clemency pleas had returned rejected by Indonesian president Joko Widodo, Sukumaran had bitterly recounted his feeling let down by Australia.

Public opinion had supported Schapelle Corby but not the Bali Nine,” Wockner writes.

Sukumaran wrote Wockner a hurt letter, wondering, “If I was white, blonde hair, blue eyes?” or a “megapin drug lord who could afford to pay millions” in bribes, could he have avoided execution.

But when Indonesia decided to execute six other drug dealers in late January “everyone knew it was a bad sign” and Sukumaran said, “I think we are close to the end.”

At Besi prison, officials acceded Sukumaran’s request regarding his execution warrant.

The document was retyped, Sukumaran signed it and was immediately handcuffed.

Next was Andrew Chan. He too demanded the documents be retyped with his final requests before he would sign.

CARAVAN OF DEATH BEGINS

The families of the condemned would be allowed to visit for the next three days, Wockner writes. But she had to urge Sukumaran’s brother Chinthu to get to Cilacap, the port town to Nusakambangan.

‘Drop everything and get on the plane, I urged him, they are serious this time,” Wockner writes. “You all need to get there. It’s going to happen.

“All the Bali prosecutors had been ordered to Cilacap. The caravan of death had begun.

“The logistics of the execution were now in full swing.”

The next morning, the men’s families left Cilacap by boat for the island.

“... Plastic chairs and corrugated iron sheeting went across to the island on a ferry,” Wockner writes. “The iron sheeting was to construct a temporary roof over the area where the nine prisoners would be shot.

“The chairs were for officials, family members, lawyers and embassy staff ...

“That night at Besi. the eight men and one woman — now the walking dead — had Kentucky Fried Chicken for dinner.”

THE LAST DAY

On April 28, the last day, visitors were limited to the island.

Back at Cilacap’s port, preparations intensified.

Nine ambulances with numbered windshields drove towards Wijaya Pura dock carrying coffins shrouded in smocked whited satin and crosses already painted with the condemned’s names and dates of death.

By 2pm over on the island, it was time to say the final goodbyes.

Wockner writes that Sukumaran’s mother and sister Raji and Brintha “were moaning guttural howls”.

Chan’s mother Helen “draped herself around Andrew, sobbing and sobbing”.

Melbourne pastor Christie Buckingham had been appointed Myuran Sukumaran’s spiritual adviser while Andrew Chan had chosen Salvation Army chaplain, Major David Soper.

“She had a list of things Myuran wanted to do on the field during the time he was tied up before the execution.” Wockner writes.

In his cell at Besi, Sukumaran was showered and ready on his floor mat and together they read from the Bible; Genesis, Exodus, Micah and Psalm 121, “the Lord will keep you from all harm”.

They prayed and she anointed him with oil, which he asked her to anoint him with in Australia where his body would be returned to for his funeral.

“The wardens formed a guard of honour to say goodbye,” Wockner writes. “Myuran and Andrew threw their handcuffed arms over their heads ... in one final goodbye.

“The shackles were put on. [Myuran’s] hands were cable-tied behind his back.”

He stepped outside and glance up at the night sky.

“When Christie was escorted to Myuran ... he was already strapped to a wooden cross that was mounted on a platform,” Wockner writes.

“His arms were bound to a cross at the elbows ... his feet were tied.

“Andrew was strapped to the cross next to Myuran.”

Each prisoner wore a white T-shirt. They all began singing.

Christie whispered to Myuran, “you are a reformed man”, and after three minutes with him had to step away.

The prisoners sang Hallelujah, the version from the movie Shrek, and then Amazing Grace.

Chan exhorted them all to “sing up! We can do better than that.”

Everyone sang until they were interrupted by the firing squad.

“A shocking boom ripped through the air,” Wockner writes.

“It was like nothing any of the witnesses had ever heard before. The sound of a hundred high-powered rifles firing simultaneously.”

*The Pastor and the Painter: Inside the lives of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran — from Aussie schoolboys to Bali Nine drug traffickers to Kerobokan’s redeemed men by Cindy Wockner is published by Hachette Australia and available now for $32.99.