How a 25-year-old former monk kept the Thai soccer team alive

COACH Ekkapol Chantawong has fought malnutrition and exhaustion to keep the 12 boys in his soccer team alive.

THE young soccer coach who led 12 schoolboys into a flooded Thai cave has been chided by some for his actions, but the families say their sons are still alive only because of him.

According to the senior coach of the trapped Wild Boars soccer team, Ekkapol Chantawong, affectionally known as “Ek”, “loves the boys more than he loves himself”.

“If he didn’t go with them, what would have happened to my child?” the mother of Pornchai Kamluang, one of the boys still in the cave, told Thai television.

“When he comes out, we have to heal his heart. My dear Ek, I would never blame you.”

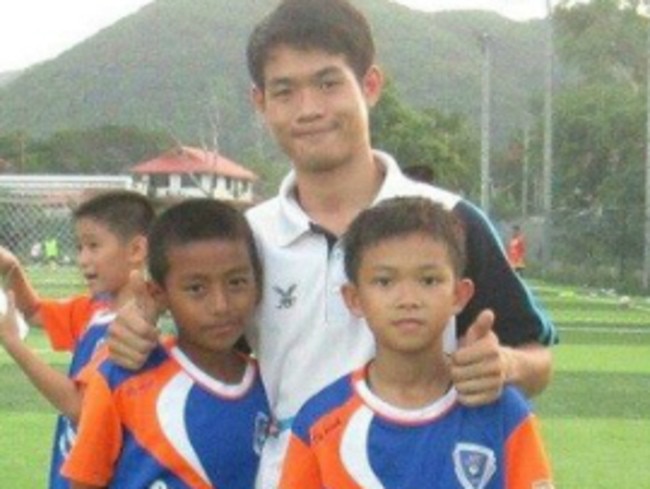

Mr Ekkapol, 25, is assistant coach to the Moo Pa (Wild Boars) Academy Mae Sai soccer team.

Weak from malnutrition after denying himself food, the former monk novice has kept the trapped boys calm in their subterranean prison by teaching them meditation.

Further details of Mr Ekkapol — himself an orphan since the age of 10 — and his incredible relationship with his young charges has emerged from Thailand.

The Moo Pa head coach Nopparat Kathawong, 37, has revealed that he handed over caring for the soccer team to Mr Ekkapol on June 23 because he had an appointment.

It was a deliberate step to give him more responsibility, starting with taking the younger players to a soccer field by the Doi Nang Non mountain range.

The field is a short drive away from the Mae Sai Prasitsart school and its Wild Boar team in the northernmost district of the Chiang Rai province near the Thai-Myanmar border.

Right near the field was a series of waterfalls and the 10km Tham Luang cave system.

Mr Nopparat advised his assistant to look out for the boys, and suggested he take some of the older players along with them on the trip.

“Make sure you ride your bicycle behind them when you are travelling around, so you can keep a lookout,” Mr Nopparat wrote in a Facebook message, The Washington Post reported.

“Take care.”

At the entrance to Tham Luang there is a warning sign about the risks of going inside during monsoon season which runs from June to October.

The older Wild Boars were due to play a match on the Saturday evening, and when they didn’t return home their anxious parents began calling Mr Nopparat.

One 13-year-old who went home after training told the head coach the team had gone exploring in Tham Luang.

When Mr Nopparat got to the site, all he could find were the boys’ bicycles and bags at the cave’s mouth.

Mr Ekkapol came to the Wild Boar team almost straight out of the Chiang Mai monastery where he was studying to be a monk.

At the age of 10, he cheated death when a disease swept through his village killing his seven-year-old brother, then his mother and father.

Until he was 12, Mr Ekkapol was looked after by extended family but was a “sad and lonely” little boy, his aunt Umporn Sriwichai told The Australian newspaper.

Relatives decided to send the boy to a Buddhist temple to train to be a monk.

Mr Ekkapol spent a decade at the temple, learning meditation and wearing a saffron robe.

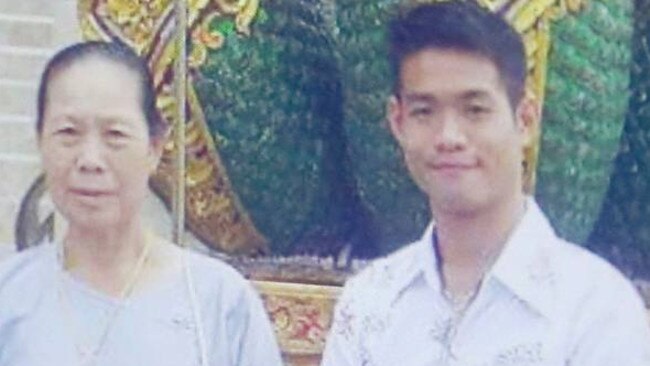

But he left the monastery to care for his ailing grandmother in Mae Sai in northern Thailand.

Then the Mae Sai Prasitsart School started the Wild Boar soccer team, which began competing in provincial competitions.

Many of the players came from ethnic minorities and poor families, stateless in the shared border region, and Mr Ekkapol related closely to these boys.

“He loved them more than himself,” said Joy Khampai, a longtime friend of Mr Ekkapol’s who works at a coffee stand in the Mae Sai monastery.

“He doesn’t drink, he doesn’t smoke. He was the kind of person who looked after himself and who taught the kids to do the same.”

Mr Nopparat has revealed that Mr Ekkapol devised a system whereby the soccer players would be given clothing or shoes if they achieved certain grades in their school classes.

He also tried to search for sponsors to help the boys achieve their dream of becoming professional athletes and drove them to and from training sessions and home.

“He gave a lot of himself to them,” Mr Nopparat said.

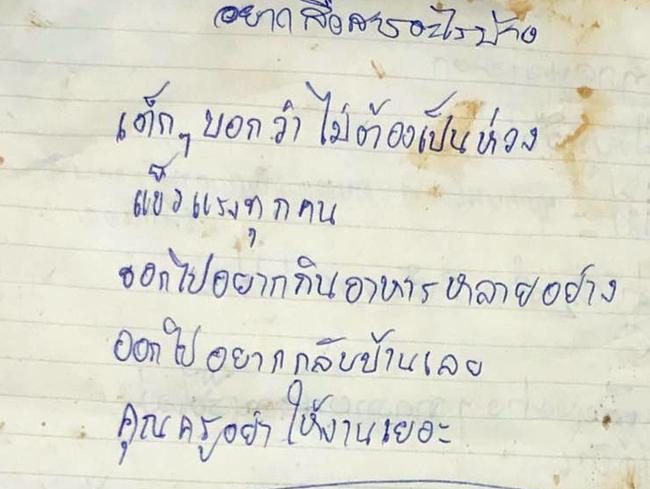

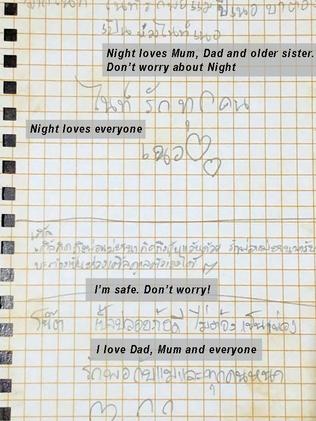

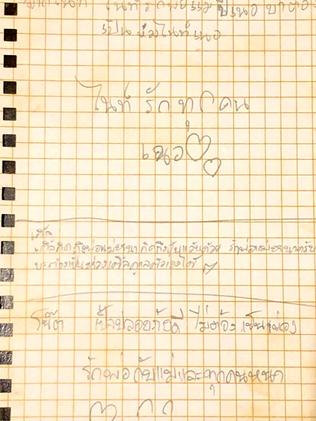

Last weekend, the Thai Navy SEALS Facebook site posted photos of letters the boys and Mr Ekkapol had written to their families.

On a yellow-stained piece of paper, torn out from a notebook, Mr Ekkapol wrote an apology.

“I promise to take the very best care of the kids,” he wrote. “I want to say thanks for all the support, and I want to apologise.”

As the world waits for the remaining seven boys and Mr Ekkapol to be rescued, they can be sure that without his selflessness and monk’s training, they might not have survived this far.

“I know him, and I know he will blame himself,” said Joy Khampai, Mr Ekkapol’s friend.