China is using torture to crack down on corruption among senior officials, activists claim

BEATINGS. Starvation. Sleep deprivation. Just a few of the techniques allegedly being used against some of China’s officials.

HUMAN rights activists have released a disturbing report into the Chinese government’s crackdown on corruption.

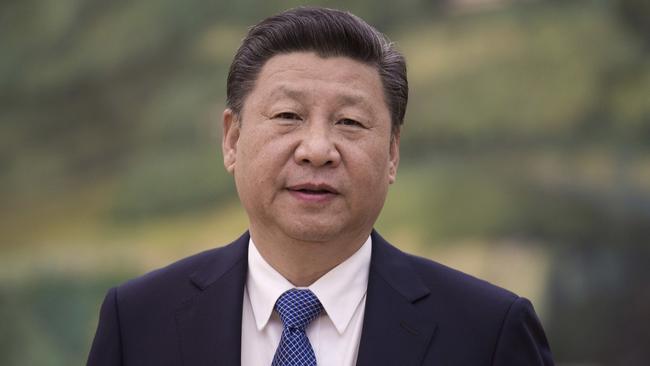

The report, which features allegations from numerous previous detainees and their lawyers, claims officials in China’s Communist Party have been brutally tortured over the past few years since President Xi Jinping assumed power.

The detained subjects are allegedly beaten, starved, deprived of water and sleep, and forced into stress positions for hours, days and weeks at a time, until they confess to a crime they may not have even committed.

Upon confessing, they are handed over to China’s criminal justice system, which has a conviction rate of 99.9 per cent.

Throughout the process, medical access, family visits and legal counsel are virtually non-existent.

CHINESE PRESIDENT’S CRACKDOWN ON CORRUPTION

Cracking down on corruption within the government was one of Mr Xi’s key policies when he came into power in 2012.

It became what is now the single largest organised anti-graft campaign in the history of China’s Communist rule.

The President’s tenure has seen the downfall of numerous senior politicians in China’s Communist Party, including former security tsar Zhou Yongkang and the former People’s Liberation Army general Guo Boxiong.

Deep-rooted political corruption has been on the rise in China for several decades. It contributes to the country’s wide income inequality and calls into question the effectiveness of the Communist Party.

After he took office, Mr Xi vowed to crack down on “tigers and flies” — everybody from senior officials down to local civil servants, in other words. Some critics believe it was more likely used as a tool to ensure potential rivals would be removed from key positions.

Anyone accused of soliciting bribes, dereliction of duty or other criminal actions would be detained without notice and interrogated by an increasingly powerful, secretive anti-corruption watchdog called the Central Commission on Discipline Inspection (CCDI), which has been in place since 1949.

The process of this interrogation is called shuanggui. As part of the internal disciplinary process, any one of the Communist Party’s 88 million members can be summoned and detained at the drop of a hat, without so much as prior family notification.

The interrogation process typically doesn’t end until the subject offers up a confession.

The whole thing is shrouded in secrecy — so much so that the CCDI’s headquarters in Beijing are not even marked.

Subjects are also isolated from any form of legal counsel and drilled on the allegations against them.

Between 2005 and 2012, the number of detained cases rose from 147,539 to 170,621.

Over the past four years under Mr Xi’s rule, that number has doubled.

SHOCKING REVELATIONS OF INTERROGATION PROCESS

Human rights activists are calling on the Chinese government to shut down the shuanggui system.

A disturbing report released today by the Human Rights Watch details the extent of the alleged torture committed by the anti-corruption watchdog against the accused, to force them into confessing.

It includes interviews with 21 people, including eight lawyers, seven family members of CCDI detainees, and four former detainees.

Yang Zeyu, a former detainee, told Human Rights Watch last year that he was tortured until he made up a story admitting to the crimes.

“They kept telling me to ‘explain problems’ … How much money did I receive, what is my relationship with that woman, and so on. They made me make it up. I had to make it up — if I didn’t they’d beat me.”

The detainees said physical assault was common.

According to the report, the subjects would be forced into padded cells without windows for lengthy periods of time — often to the point where they would no longer know the difference between night and day.

“If you sit, you have to sit for 12 hours straight, if you stand then you have to stand for 12 hours as well,” a former detainee told the organisation. “My legs became swollen, and my buttocks were raw and started oozing puss.”

Another detainee said he was forced to stand for 23 hours a day for more than a week while balancing a book on his head.

He said when he could no longer stand it, he gave up and confessed.

“After he said it, he was allowed two hours of sleep every day,” the lawyer said. “At that point his feet were swollen like an elephant’s, and he could no longer urinate.”

Sleep-deprivation was another prominent torture technique used, according to the report. One subject, Zhou Wang Qiuping, told Human Rights Watch he was forced to drink dirty water, had a dozen lit cigarettes shoved up his nose, was beaten with steel bars and iron war until he fainted, and was waterboarded — a torture process in which one’s face is submerged in a basin full of water to simulate drowning.

One detainee, Ren Zhiqing, told Human Rights Watch he became so sleep-deprived in the brutal process that he started hallucinating — an inevitable side-effect of prolonged lack of sleep.

“In the first eight or nine days, they required that I sit in certain ways and I wasn’t allowed to move ... I began to hallucinate, as if I had split into several people at once. This was because I was tired: sitting all day from 6am to 11pm, then being interrogated at 11pm, and only after that do they let you sleep.”

Another detainee, Lu Yicheng, said: “[They] shined dozens of 1000 watt lights on me at all times, and didn’t turn them off at night so I [often] couldn’t sleep at all.

“Even if they let me sleep, before I slept they made me drink large amounts of water before I could lie down, so that as soon as I closed my eyes I felt I had to urinate, so I couldn’t sleep in peace.

“But when I was so extremely tired … and closed my eyes they’d shake my bed with a great force, pulled my mattress, or clapped their hands loudly on top of my head, so I couldn’t sleep.”

Several interviewees told their lawyers food and water were denied, and used as a means of control and coercion.

One detainee said: “In the beginning they let you drink water, but after three to four days, they said, ‘You want to talk about your problems?’ and if you weren’t able to tell them, they didn’t let you drink it. If you did, he used one of those disposable cups to pour a little bit of water for you.”

Human Rights Watch has urged the Chinese government to immediately abolish shuanggui, release all detainees and ensure that they have regular access to lawyers, doctors and families in the meantime.

The organisation says it has contacted the CCDI and three government departments with questions about the report, but has not received a response.