The five rules of Africa

THERE are five rules to follow when visiting Namibia. But some rules are made to be broken, writes Gretel Killeen.

SOME people are happy living in a cotton-balled world where even a trampoline has safety walls

But some – perhaps mad – people need to break rules and be unsafe. I’m one of them.

I guess that’s why I married after dating for just 13 weeks, why I agreed to host the Logies and why I ended up in Africa watching a headless rhino being eaten by three lions, with a bloke I’d accidentally met about 10 days before when a friend forced me to join Facebook.

Let’s call this bloke Jack. We had dinner in Sydney on a Sunday night and discovered the only thing we had in common was a love of wine.

Three days later, we met for a wine and discovered we had one more thing in common; a liking for salted peanuts.

It was all looking pretty flat-line until the following morning when Jack emailed asking if I wanted to go dutch on a trip to Africa. And suddenly he became fabulously interesting.

Sunday

So two weeks after the day we first met, Jack and I caught up once more when he picked me up in a cab and we drove to the airport for a flight to Johannesburg. Our only baggage was hand luggage, in my case a $30 school backpack bought from a $2 store.

Just past check-in we agreed to do a road trip in Namibia because neither of us had been there. We booked a flight from Johannesburg to the Namibian capital Windhoek on the internet while having a wine in the Qantas Lounge. Then we boarded our initial 12-hour flight, the duration of which was actually longer than the total of all previous time spent in each other’s company.

Much of this flight was spent listening to the African expat beside us who said ‘‘there are only five rules in Africa’’:

1. Never drive a car that can be identified as South African;

2. Always let someone know what road you’ll be on;

3. Don’t drive after dark;

4. Stay on sealed roads; and

5. Never pick up hitchhikers.

Monday

Jet-lagged in Johannesburg at 4am we check our return flights from Namibia and accidentally book to leave the country before we’ve actually arrived.

On the plane to Windhoek we resolve to rent a four-wheel-drive at the airport, but there we learn that all 4WDs were booked out a month ago.

All but one car hire place tells us we can’t possibly do a road trip in a two-wheel-drive, so we rent our car from the people who say we can.

I collect a map and some pamphlets.

We have a book on how to find your way round Namibia but unfortunately

I misplace it. There’s no room for a book in our tiny Japanese car anyway.

The biggest part of the car appears to be the bumper bar, upon which is a massive sticker announcing that we come from South Africa. We therefore break rule No.1 and, as we drive off, we also break No.2, because we don’t tell anyone where we’re going. But in our defence we can’t tell anyone because we don’t have a clue.

It’s mid-afternoon and hot. The sky is edible blue. Windhoek is low-rise and ordered. You can feel the influence of the late 1800s German colonisation.

We head west and an oncoming car flashes its lights. Terrified we prepare to be ambushed. Instead we pass a parked policeman who appears to be pointing a hair dryer at the traffic. We would have been busted for speeding had a group of eight baboons not chosen that moment to cross the road and force us to slow down.

Only two million people live in Namibia and, beyond the towns, rarely a person is seen.

For an hour and a half, through the town of Okahandja, past signs warning us of springbok and warthogs, Jack and I politely talk about our childhoods. We turn left and travel nearly 300km past golden grass before a distant hard rock mound backdrop.

As the desert begins the night falls and we’re driving in the dark – breaking rule No.3.

Our destination is the allegedly ‘‘quaint’’ coastal town of Swakopmund, which feels like a European ski village before the snow.

We both love African Africa so Jack and I also discover the bond of disliking the same things. Our lack of planning leaves us with overpriced accommodation and dinner at a restaurant whose main selling point is its view, which we can’t see in the dark.

Tuesday

Dipping toes in the freezing Atlantic we decide to drive the 230km via Walvis Bay to the world’s biggest sand Trans Kalahari Highway.

With the endless, empty pure white desert on one side and the dark blue sea on the other we pass a single road sign that simply says, ‘‘SAND’’. Then, past grey dirt desert fringing short grasslands we turn on to an unsealed road and break rule No.4.

There are no other cars on the winding rock-shrouded road. We’re fearful that our car won’t make it and start to feel sorry for it.

We drive on, discuss the meaning of life and have a fight about it. We cross the Tropic of Capricorn. In isolated Solitaire, which is actually a petrol station, we eat tomato sandwiches that taste like they did when we were kids.

Nearing Sossusvlei we organise the night’s accommodation. To do this I check the suggestions on the map, the ads on the back of the map and the tourist pamphlets and then apply a simple equation of ‘‘location plus price plus photo quality plus font size’’.

Remarkably our choice is available, small huts perched in the scrub below the hills.

By the pool, under the stars, we’re served a four-course meal including springbok goulash, oryx and eland steak.

As a non-meateater, I’m quickly learning that for tourists this is a land of ‘‘see it, photograph it, gobble it up’’.

Wednesday

At sunrise we drive to Namib Naukluft Park. The landscape folds into massive endless burnt-orange dunes.

To preserve our car we pay a local in a 4WD to take us on a round trip to the dune base but as soon as he’s dropped us off he leaves and, after being stunned by black tree silhouettes and dry bleached salt pans that last contained water 800 years ago, we grab a lift back with some scared Europeans.

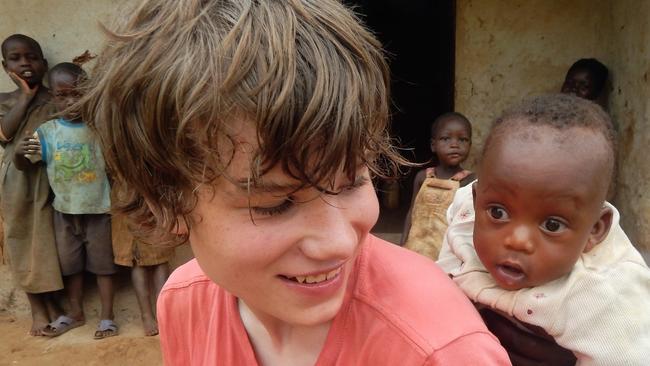

We decide to finish our trip in the north of Namibia in wildlife-filled Etosha National Park. While there, a malnourished boy flags us down. We break rule No.5 giving a lift to him and his exceptionally thin Bushman dad.

About 220km later we drop them in Maltahohe, their town of choice.

Mid-afternoon we stop for petrol at Mariental where women are washing themselves, their babies and their clothes in the bathroom basins.

We begin the day’s final three-hour drive to our accommodation, just north of Windhoek, a thatched melted-roof house run by devout white Christians, like The Sound of Music’s Von Trapp family, but without the outfits.

As the daylight ends, 100km from our destination, we hear our massive bumper bar crash on to the road. We put the bumper bar in the back sea and continue our drive while discussing belief systems and whether or not our car rental will cover the fact that half the car ‘‘just kind of leapt off’’.

Thursday

It’s 38C. We drive 230km to Otjiwarongo, 183km to Tsumeb and another 74km to our accommodation, one of six tree houses overlooking a wonderful waterhole.

On arrival we’re popped into a sideless 4WD to enter the national park and spot the aforementioned rhino-eating lions with three German couples sporting the kind of camouflage safari gear worn by explorers 200 years ago.

We return at night to a five-course feast, served by four wonderful Zimbabwean economic refugees. Oddly, the main subject of conversation is ‘‘where is the back of your car?’’

Friday

At dawn, warthogs, springbok, wildebeest, orix and zebra all come to the waterhole to play.

Today’s our flight to Johannesburg and home. Massively underestimating the drive time to the airport we break the speed limit for seven hours while discussing the global economic crisis, global warming and whether cleaning the car with babywipes will make the absence of the huge bumper bar less obvious.

Breaking more rules, the car rental manager does no more than giggle when he sees our backseat passenger and we check in moments before departure. The trip has been a huge success. So will Jack and I see each other again? Who knows, maybe there are no rules.

Gretel Killeen’s latest book is The Night My Bum Dropped (Viking, $29.95). That and this article may both be gleefully exaggerated.