A tour of Rio's biggest favela

SEWAGE, guns and labyrinthine streets - we take a tour of Rio's biggest favela, and live to tell the tale.

"YOU can take photos at any time," said our guide, Luiz, a jovial, bubbly, highly likeable chap.

He turned to look at the men loitering behind us. Then turned back. The expression on his face had changed markedly.

"Don't take any pictures now though," he said urgently. "Not at the moment. Please don't photograph those men over there behind me."

We knew instantly who he meant. Three men with machine guns slung over the shoulders are guarding the entrance to Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro's largest favela - the tour's destination.

Favela history

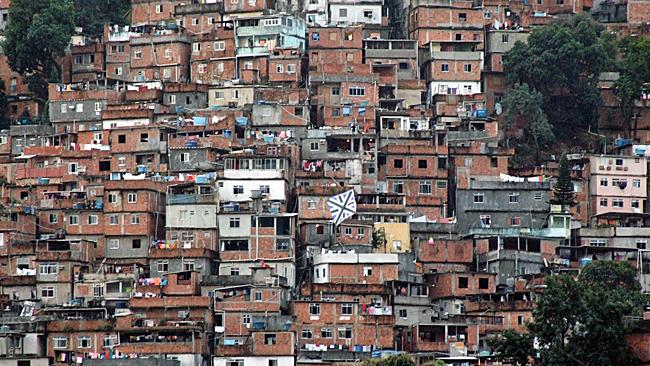

A favela is the Brazilian name for what's often called a shanty town or slum.

The illegal settlements emerged in the late 1800s when dispossessed former slaves and soldiers gathered together as socio-economic outcasts. Favelas grew more rapidly in the 1950s when swarms of Brazilians swapped urban for rural in pursuit of work.

The critically-acclaimed 2002 film City of God about life in a 1970s favela showed a lawless underworld, where bullets made the law.

At the last count Rio has 513 favelas and, with the exception of occasional heavily armed raids targeting drug lords, the police stay well clear.

The notorious neighbourhoods are often positioned on the hills in the centre of Rio, on what would otherwise be prime real estate. It's a small poetic justice that the city's poorest citizens have millionaire views.

At first, the idea of touring a favela seemed like a sick post-modern joke ("what, we pay money to go and stare at poor people?") and about as sensible as tickling a great white shark.

But after talking to travellers who'd done the tour, curiosity got the better of me.

Normally, for a gringo like me, a favela would not be a safe place to go, but I was about to have my preconceptions turned on their head.

We got a nerve-jangling motorbike ride to the top of Rocinha, the plan being to walk down through the middle of it. The three men with machine guns were a reminder that this wasn't a show put on for tourists. This is real and the locals live dangerous lives.

We, on the other hand, are very obvious and easy targets (large cameras and sunburn are always a give-away) and the police weren't going to be watching our back.

Luiz turns and walks straight towards the favela "soldiers"... and then straight past them, down a narrow alley.

The small group follows nervously in single file. I couldn't resist exchanging eye contact with a gunman wearing a Manchester United shirt. They knew who we were, but didn't seem bothered.

Inside the slum

The labyrinthine streets are narrow and dark, with electrical cables and graffiti everywhere. It smells bad and there is no mistaking the water running in the gutters is sewage.

Luiz said we would not get robbed, but I didn't believe him.

However, the locals don't pay us much attention and I begin to slowly relax the grip on my camera. Then we turn the corner to find four youths blocking our path, each holding an object.

A drum beat starts, then another, then another, a higher tone. They are a band, playing especially for us, on recycled rubbish, on barrels and tins.

The boys are smiling and so are we.

At the end of the concert we all put some well-deserved change in their kitty box. This sort of thing happens time and again.

Unexpected treasure

We see (and buy) amazing jewellery made from rubbish - a gorgeous bracelet made from multi-coloured electrical wire - and, more impressive still, art.

We are taken inside a house-cum-gallery, where locals paint pictures about their lives in the favela.

It is irresistibly poignant stuff and there is some seriously good art there too.

Kids come up to say hello. They're not begging or even expecting money, they just love having their photographs taken on digital cameras where they can see the results.

No one was going to hassle or rob us because everyone understood we were bringing money into their community - and taking a greater sense of appreciation away.

Far from fearing for my life, the tour made me smile and laugh. But we were also constantly reminded that it's a hard life in a favela.

The most inspiring part of the experience came at the end, when Luiz took us to a day centre where tourist money was to be used to great effect. Before he set up the tour company, orphaned children were forced to beg, but now they're off the streets and being cared for and educated.

Seeing these children, raised in lawless poverty, it was impossible not to feel deeply lucky about the lottery of birth - and make donations to their cause.

Instead of handing over money at gun point, I was handing it over because of smiling children.

More: To book tours or make donations, visit www.bealocal.com. The company also arrange ‘favela parties' and football tours. Top Tips: Rio de Janeiro destination guide

Top Tips: Rio de Janeiro destination guide Travel Advisor: The latest expert information

Travel Advisor: The latest expert information Wego: Book your trip on news.com.au

Wego: Book your trip on news.com.au