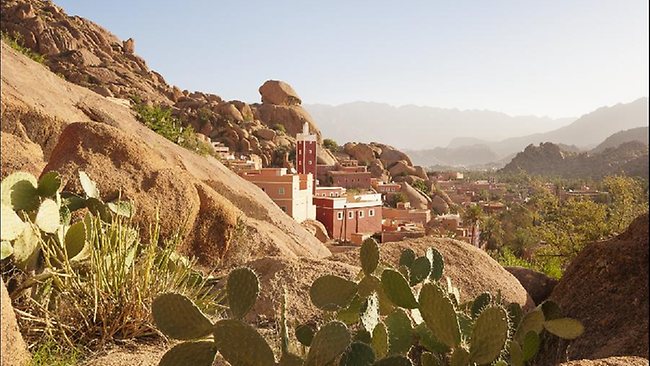

Search for lost oasis in Morocco

NORTH of the Sahara and east of the Atlantic shore is the least known of Morocco's great mountain ranges. Meet the people of the Anti Atlas, for whom walking is a way of life, writes Horatio Clare.

"THEY call me Hammou Le Philosophe," he laughs, as the sun rises over the hill town of Tafraoute and we head south towards the plateau.

The argan trees are deep green under lucent sky, the morning as tranquil as any these mountains can have known in their 300 million years.

The way to explore them is to walk: for many people here, walking is both a way of life and a way of changing life.

My guide, Hammou Amechghal, and I are embarking on three expeditions in the Anti Atlas: a downhill stroll and a flat walk will be preparation for a two-day hike in the Ameln Valley and up the red-gold ramparts of Jebel L'Kest. We go quietly - we are both incomers.

Hammou came from near the Algerian border, and walks here because this place altered him.

"Women, kif (cannabis), alcohol, two packs of cigarettes a day - I committed all my follies before I was 40! Then I came here and changed."

He raises his chin to the high chameleon peaks of Jebel L'Kest, which overlook Tafraoute from the north, their colours shifting with the play of light through spectrums of ochre-pink.

"This made the difference. A place where you can breathe."

He smiles the mischievous smile of the semi-retired sinner.

"The Prophet says, as long as you change by age 40, you're OK."

Negotiation with norms, their adaptation and, sometimes, outright rejection are characteristic of the area. The Anti Atlas is Berber country. The populace descends from Morocco's indigenous inhabitants: with the arrival of Islam in the seventh century, the mountains became fortresses of Berber ways.

Many Berber people call themselves Imazighen, or "free people" - and they're not to be underestimated.

They resisted Roman and Ottoman attacks across north Africa, converted to Islam in the ninth century, and in the 11th formed the body of the Almoravid dynasty, which ruled an empire from Ghana to southern Spain and Portugal. The last successful invaders were French colonialists, who used Tafraoute as their headquarters.

Today the Anti Atlas is less remote in geography - only a two-hour drive from the city of Agadir - than it is in time and tradition. The approach road is a narrow, twisting ascent, occasionally blocked by livestock.

In the centre of Tafraoute, sheep make their way up a dry stream bed. Market traders busy themselves manufacturing babouches - leather shoes, locally regarded as the only footwear worth wearing - and a young businessman veers, horrified, around a drunken snake charmer.

--- A stroll en route to the Sahara

Down the gorge at Ait Mansour: 6.5km; 2 1/2 hours The potentate of this region is the Sahara. The desert to the south gives the Anti Atlas its exalting light, its star-clear nights and blazing noons. A Berber story says that the desert was once a green place of running water and bird song. All men and women were honest and kind.

Then, one day, someone lied. It was only a small lie, but God drew the people together and said: "Because someone lied, I'm going to drop a grain of sand on the world."

The people thought, well, that's not much.

But God said: "For every lie, I'll add another grain."

The reason there are oases, the story says, is that some people are still honest and kind.

In Ait Mansour gorge, the paradise of the story endures.

Beyond the plateau south of Tafraoute there is a fissure in the granite escarpment. At the bottom is a stream bed thick with palms, their dates clustered like golden bees.

We walk under pomegranates, olives and figs. The walls of the canyon are dusty orange and paprika. Driss, a farmer, sells five kinds of dates. He has more than a hundred palms.

"But my daughter is in England, my sons away in the cities. No help for the harvest. The young people go away," he says. It is a part lament, part boast.

I walk on down the gorge, listening to the bird song and the chergui, the Saharan wind, which shushes like a ghost river through the palms. It is Friday, mosque day, and the day for ma-harouf: charity to travellers. As the palms give out and the heat swells, I long for shade and succour.

In the village of Agerd Amlalen, at the foot of the gorge, 30 women gathered in a yard beside the mosque are absolutely insistent that I must come in, wash and feast. They serve a delicious thick-grained couscous, with eggs, garlic and lentils.

The women will take no payment - the food is given "fi sabilillah", to honour God.

Amid the woodsmoke, the chatter and the squeals of children, the atmosphere is as high-spirited as a hen party.

As I leave, waved off with blessings, it is as though I had journeyed through that Berber tale, to a place where people were honest and kind.

--- A circular walk, via the Blue Rocks

Route starting and finishing in Tafraoute: 6.5km; four hours "You know why the flies are smaller here, on the plateau?" Hamou asks, on my second trail - our "philosophical" walk in the environs of Tafraoute.

"Because they are interns. The professionals go to town."

The sly humour of this lies in the reference to depopulation, which makes the area so beguiling to walk in, but perhaps melancholy to inhabit. Everywhere people say, "the young go away, to the cities". If they return, they build modern houses near roads, leaving the fort-like villages to decay into the mountainsides.

Not that those left behind are outwardly mournful. Two Berber women beside the path are securing large bundles of firewood. Hammou rushes to help one hoist her load. The weight staggers him. The lady takes the strap around her forehead, derides his weakness and plunges off into the bush, singing.

Intern flies are the favourite prey of the grey-backed shrike - a burst of pied-wing beats among the green of the argan trees. Known as the tomb-bird, the shrike makes a larder of insects, impaling them on thorns. Hammou pauses by a leafless argan and snaps one of its silvery twigs. "See? It's alive - this is a very patient tree. It sleeps through drought."

Argans are indigenous to western Morocco. Their nuts are hand-ground in a stone mill to produce a nourishing oil. The trees are also living hayricks for Berber goats. A farmer herds them using sling-shot stones, driving them up into the branches, which the goats climb easily.

Our walk takes us past peach-coloured tors of granite, many with local names. There is Napoleon's Hat, a sphinx and a tortoise, and here a collection of bright blue mushrooms. Around us are huge boulders painted pink, green and grey, as well as the dominant lapis blue.

They are the work of Jean Verame, a Belgian artist who enlisted the help of the fire brigade for his project in 1984.

"He did it to please his wife," says Hammou. The blue rocks are a favourite site for picnics and parties on summer nights. Their main artistic effect, on this limpid morning, is to highlight nature's effortless superiority over man as a sculptor and manipulator of light - perhaps that was Verame's point.

We circle past a red-painted mosque at the village of Aday and arrive at one of the few Berber houses in the region that is still occupied. The owner, Mahfoud Idihi, has eschewed the pull of the cities.

"I want to keep our heritage alive," he says. "Our patrimony. I am the last generation of our family to live here. Please, come in."

The architect Le Corbusier once said "a house is a machine for living in". The traditional Berber dwelling is a miraculous, integrated and embracing device. Built like a miniature fortress, it has separate entrances for animals, family and guests.

We stoop through low passages which spiral around the heart of the machine: the kitchen. A hole in the floor means organic waste can be dropped to the animals below. They function both as central heating, in winter, and as a recycling centre.

"Smoke from the cooking fire protects the ceiling from insects," says Mahfoud. "Notice that the kitchen is raised up a big step to stop babies coming in. There will be 10 or 11 people living here, lots of children. The house is designed for all of them."

Mahfoud shows me the granary.

"We keep treasures in here, hidden under the wheat."

After that, the women's sleeping quarters, the passages which double as nurseries, the roof where they sleep in summer and the space for drying dates. Built of earth, stone and palm, the Berber villages decay gracefully, returning themselves to the earth.

Walking through them is an eerie experience - they are teachers as much as memorials, offering a model of existence in harmony with the environment; something the most advanced architects of our time struggle to achieve.

Near Mahfoud's house is an ancient rock carving of a gazelle. Two schoolgirls have climbed up to the ledge above it and are dancing to music played from a mobile phone. They wave and giggle. Morocco's prehistory and its future side by side.

The girls' lives will be entirely unlike those of generations of women before them, Aisha Taboudrart explains, when we join her for lunch after the walk. Aisha inherited her father's argan-oil business, which she has supplemented with a convenience store.

She also offers traditional meals to visitors. As we eat a rich couscous with argan oil, eggs and honey, Aisha tells me, "A few years ago, I could not even have walked to market in Tafraoute without a husband or some male relative. Now I can go wherever I like. I travel to Agadir, to Casablanca, on business."

--- A hike along an old drovers' path

Tafraoute to Tagoudiche and back: 24km; two days, with an overnight stop If the best walks are the oldest - the pilgrim trails and the ancient ways - then the most delightful of all are the drovers' paths, their contours forgiving, their prospects timeless.

My two-day hike follows a drovers' road north from Tafraoute, into the Ameln Valley and up the escarpment of Jebel L'Kest, along the track farmers use to bring barley, livestock and oil to market in Tafraoute.

We bear northwest out of town, crossing rising ground towards a low escarpment, as Hammou shows me the tracks of porcupines and places where wild boar have foraged. We pass a giant boulder, its top piled with thousands of stones.

"People add one for good luck on their way to market," he explains.

We breast the pass and descend into the Ameln Valley.

We follow irrigation channels out of the valley floor, up towards the mountain. In the palm groves below the village of Tamalokt is a cistern, a place of utter peace, where scarlet dragonflies skid above the water and the tops of olive trees sway against cerulean sky. We lunch on tinned sardines, digest and set off.

The first ascent is a hot scramble as we cut upwards across screes of rock, aiming for the track which goes up to Tagoudiche, our destination, a village at 915m.

When we reach the piste, the valley falls away below us, receding towards the west. In the heat and the haze, the view could be another earth, African-ochre, vast as God's hands cupped.

As we go higher, we pass terraces baized with fine green. Now there are pallid swifts sowing the air with their soaring, and two falcons - and higher still we startle a covey of partridge.

A horizon of vast, hunched mountains south of Tafraoute is visible now, while ahead are rock strata bent like tusks, whorled like ears, bared like teeth. Here the phrase "as still as stone" makes no sense: the mountains are as alive as stone, as fluid and as mighty as geological force and time.

At sunset we arrive at Tagoudiche, a village in the crook of the mountain's arm, with one street, one shop, seven women gossiping, one black cat, a mosque and a feeling of eternity somewhere above its rooftops.

Our hostess is Fatima Monhi, a tiny woman, delicate as a kestrel, who has been providing bed and breakfast to hikers for 20 years. Her house is a natural stop-over for the climb up to Jebel L'Kest, 915m above us. For her, Fatima says, walking is pilgrimage.

"Yes, I go up Jebel L'Kest sometimes," she nods.

I can scarcely believe it. Her legs are not much longer than my arms, and my legs are aching.

"Oh yes. A marabout - a holy man - is buried there. I go to consult his spirit. Lots of women do," she says.

"I ask for rain, for good business, for peace.

"Five days ago I went up and asked for food and health. And look ... "

She spreads her hands at the steaming chicken tagine. "It is granted."

After supper, I stand on the rooftop terrace of Fatima's house and take in the silence of the mountain night under a downpour of starlight. As constellations within constellations of stars blink and glitter, it seems as though the holy man of Jebel L'Kest has granted me something that I had not yet thought to ask for.

My walks in the Anti Atlas have led me to something celestial and eternal, infinitely peaceful, so distant and yet - just there.

--- Horatio Clare is a writer of travel and fiction. In his upcoming book, Down to the Sea in Ships (Chatto & Windus) he sails the oceans in the company of seafarers and their cargo.

--

-- Copyright Lonely Planet Traveller magazine. Words: Horatio Clare. Pictures: Simon Urwin. First published February 2013