Virgin Australia collapse: 7-year spiral finally brought VA to their knees

Lockdowns have crippled all the world’s airlines but few more so than Virgin Australia, where a seven-year spiral finally brought it undone.

Virgin Australia was, in some ways, perfectly suited for our era. Much like a technology start-up, it never made money, just promised to make money in future.

It sold its product at less than it cost to make, all the while using a heavy flow of investor money to subsidise its loss-making operations.

But when the lockdown came, Virgin discovered it was not much like an online retailer or an app maker after all. It suffered a near-total blackout from the lockdown. Virgin tried too hard and spent too much, and when the tension came, the company was stretched so hard it snapped.

Virgin’s loss-making is legendary. It has had some big statutory losses and some even bigger ones. Last year it lost $315 million. The year before that $650 million. In 2017, $186 million.

In 2016, the loss was $225 million. It’s a dismal record.

RELATED: Parties show ‘keen interest’ in resurrecting Virgin

RELATED: Virgin freezes Velocity points

All the while, however, Richard Branson has been smiling through his blond goatee. The English entrepreneur who owns the Virgin brand name has been collecting a licensing fee for use of the name. Details of the licensing deal have not been public since 2015, but at that point it was reportedly around $10 million a year.

HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?

The airline was launched as a discount carrier called Virgin Blue back in 1999, and in 2012, they decided to become a full-service airline, with lounges and nice food. They ditched the colour blue from their name and adopted much more red colour scheme, as they attempted to minimise the difference with their big competitor, Qantas.

Virgin hired a senior Qantas executive as CEO and tried to out-Qantas the flying Kangaroo.

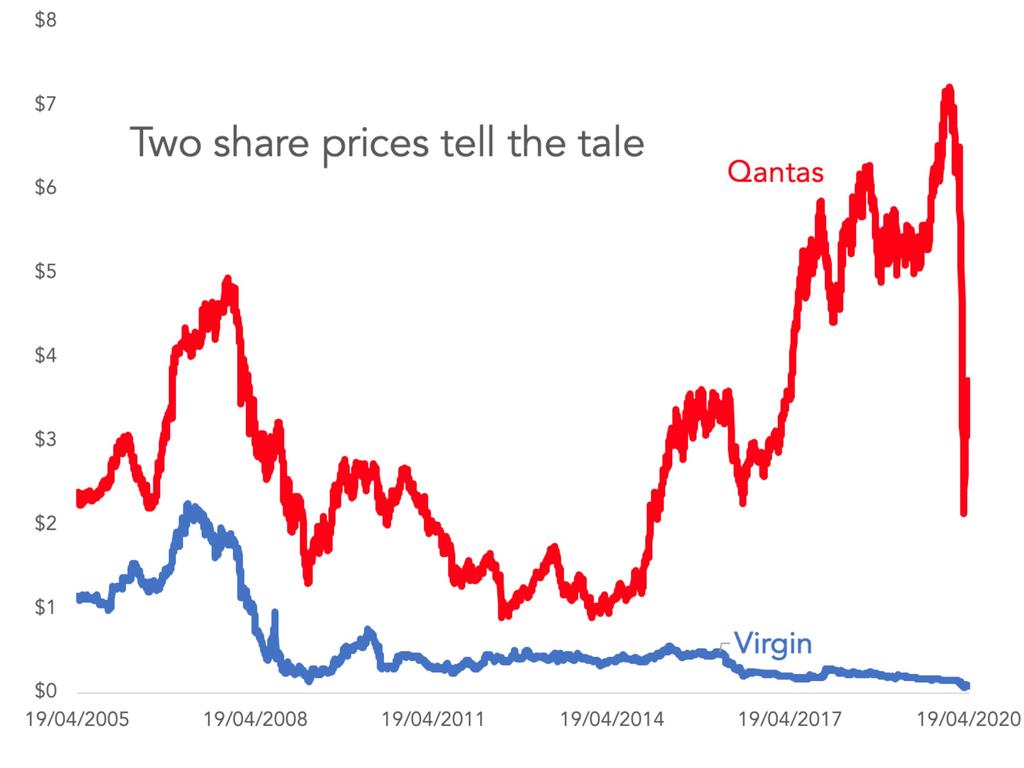

As the next graph shows, it never quite could. Virgin’s full-service business model failed to ever get fully airborne, and that meant when a bit of turbulence came along it had too little room to manoeuvre. As we have seen, it crashed hard.

There was only room for one fancy airline in this country, apparently. What the above graph does not show is the astounding amount of debt that Virgin accumulated as it played the emulation game. By the time of its most recent financial report, it was paying interest on $5.3 billion in debt.

One particularly glaring example of that debt? Virgin spent $700 million in 2019 to buy back a big chunk of its own frequent flyer program, called Velocity. The private equity investment company Affinity capital partners had bought Velocity in 2013 for $335 million. To fund the buyback, Virgin raised a huge sum of debt, using unsecured bonds.

That word – “unsecured” – matters a lot now. When a company goes into administration, it can get out of paying some of its debt. There are two types of debt – secured and unsecured. Bank loans are always secured debt, which means they get paid back first.

Employee entitlements are also guaranteed, by government. But everyone else is at risk.

The poor suckers who loaned Virgin unsecured money to buy back Velocity are ruing their decisions now.

Incidentally, while Virgin Group is in administration, and Virgin Group owns Velocity, the company insists Velocity is not in administration. Your points balance is safe! However don’t try cashing them in for wine or a breadmaker just now, as they are on “pause” according to the administrator.

What about assets? Virgin has, according to its financial documents $2.8 billion worth of planes and such. But it pledged $2.3 billion of them as collateral for various loans. That collateral could be scooped up by creditors now, but the value of planes is in, ahem, a little lull right now. Trying to go for a fire sale of aeroplanes at this moment would be insanity. It might be smarter to leave the planes in Virgin’s hands and hope they can start flying them again one day soon when they come out of administration.

We all hope Virgin comes out of administration at some point. The worst case scenario would be if it does an Ansett and gets liquidated. The much better scenario is that it shakes off some of those unsecured creditors, and gets back into business under a much lighter debt load.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.