What caused the deadliest plane crash in world history

On a small holiday island, a chain of events unfolded that culminated in the worst plane crash of all time, forever changing how we fly.

It was an unfortunate series of very unfortunate events that led to the deadliest aviation disaster of all time.

On a Wednesday 42 years ago, the world reeled with shock when two packed passenger jets collided at the airport on Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands.

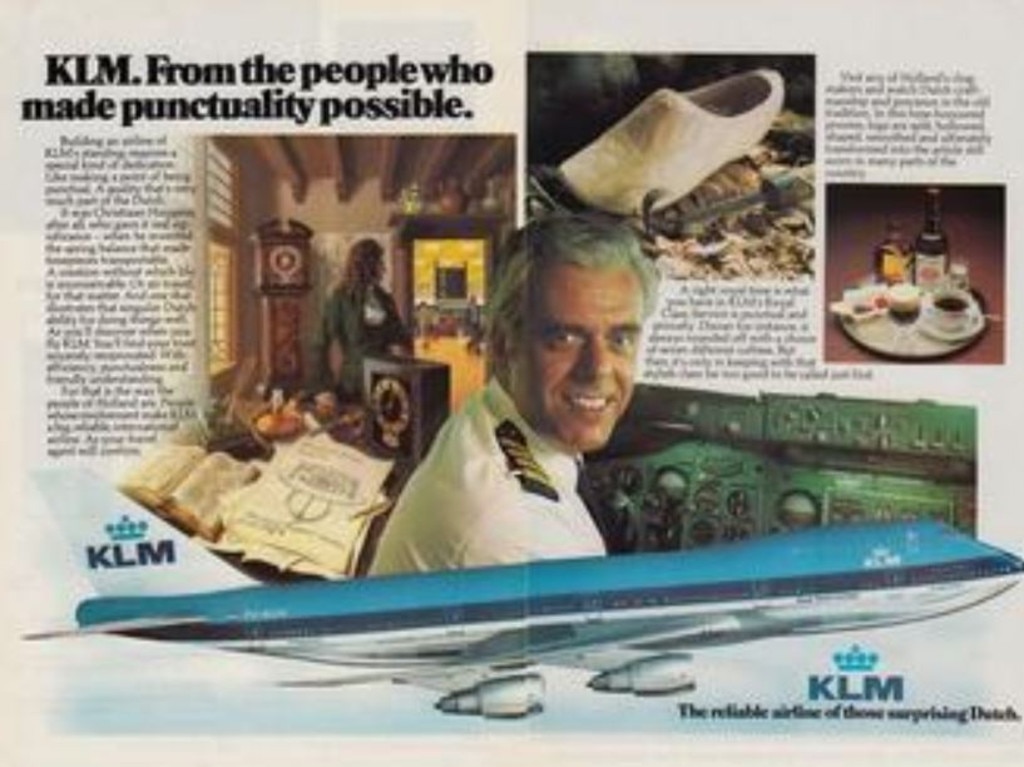

Two Boeing 747s — one operated by Dutch carrier KLM, the other by now-defunct Pan American — collided on the runway, causing a catastrophic fire that killed 583 people on both aircraft: an aviation death toll not seen before, or since.

Unlike the recent tragedies of the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes, which have been blamed — so far — on the aircraft itself, the Tenerife disaster was the culmination of bad luck and human error, which would change what happened in cockpits forever.

Neither of the doomed planes should have been on Tenerife island on March 27, 1977 but as fate had it, they were.

The Pan Am plane had come from Los Angeles via New York City and the KLM plane from Amsterdam, and both were heading to Gran Canaria, another of the Canary Islands.

But a bombing at Gran Canaria airport by a local separatist group forced air traffic to divert to the usually quiet regional airport on Tenerife — the first unfortunate event that would set the runway calamity in motion.

A PRELUDE TO DISASTER

A few hours after both planes were diverted to overwhelmed Tenerife airport, Gran Canaria was finally back in business.

The Pan Am plane was ready to take off but its path was obstructed by the KLM plane, which was ahead and needed refuelling.

By the time it had refuelled, a heavy fog settled over the airport at Tenerife. As pilot and author Patrick Smith wrote in his analysis of the disaster, had Pan Am been able to take off when it was ready, it would have beaten the fog.

The bad weather meant neither aircraft could see the other, and air traffic control tower couldn’t see either of them. At this regional airport, there was no ground tracking radar.

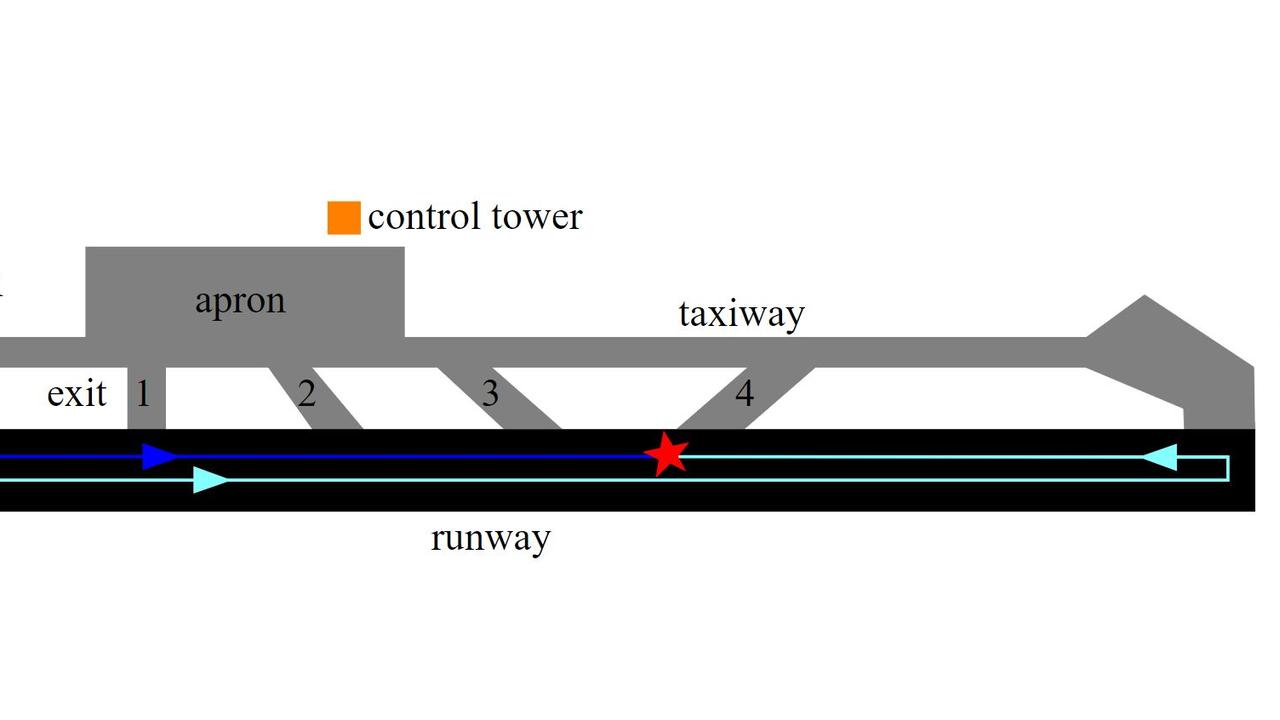

Another complication was congestion at the airport, which had cut off the usual access to runway 30, which the planes were using to depart.

To take off, each plane had to taxi down runway 30, get to the end, make a 180 degree turn, and take off in the direction it had taxiied from — similar to how models walk and turn on a catwalk.

As both aircraft taxiied down runway 30, preparing for departure, KLM was in front, with Pan Am trailing behind.

KLM reached the end of the runway and turned, awaiting clearance to take off. Pan Am was to move into a left-hand taxiway, so the runway was clear for KLM’s takeoff.

At least, that was the plan.

‘THAT SON OF A B*TCH IS COMING’

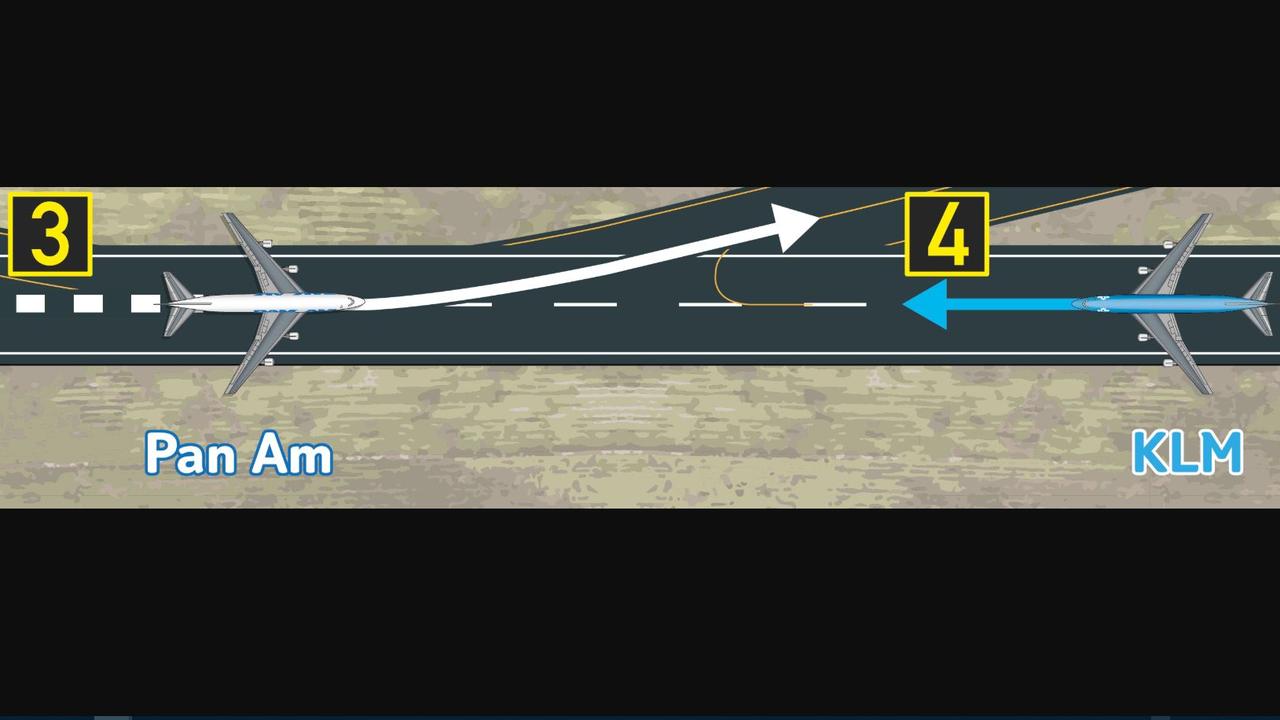

As the KLM plane sat at the end of runway 30, in position and holding for takeoff, the Pan Am pilots missed the taxiway they were meant to turn into. They could use the next turn, but it meant they were on the runway for longer.

Meanwhile, the pilots in KLM got a route clearance from air traffic control. The route clearance had come unusually late, due to the unusual circumstances of the day. The KLM pilots mistook it for takeoff clearance.

Poor communication between both cockpits and air traffic sealed the terrible fate of both aircraft and everyone on board.

As Smith explained, communication was via two-way VHF radios, and on these radios, if two transmissions were sent simultaneously, they cancelled each other out — leading to words being missed and messages misunderstood.

The Pan Am crew and air traffic control knew Pan Am was still on the runway, and despite efforts to tell KLM, the KLM crew — thinking they were cleared for takeoff, and unable to see due to fog — didn’t realise.

It was only as the KLM jet started thundering down runway 30 towards Pan Am as it tried to take off that the horrible reality of the situation set in. “There he is!” Pan Am captain Victor Grubbs yelled, in a cockpit voice recording. “Look at him! Goddamn, that son of a bitch is coming!”

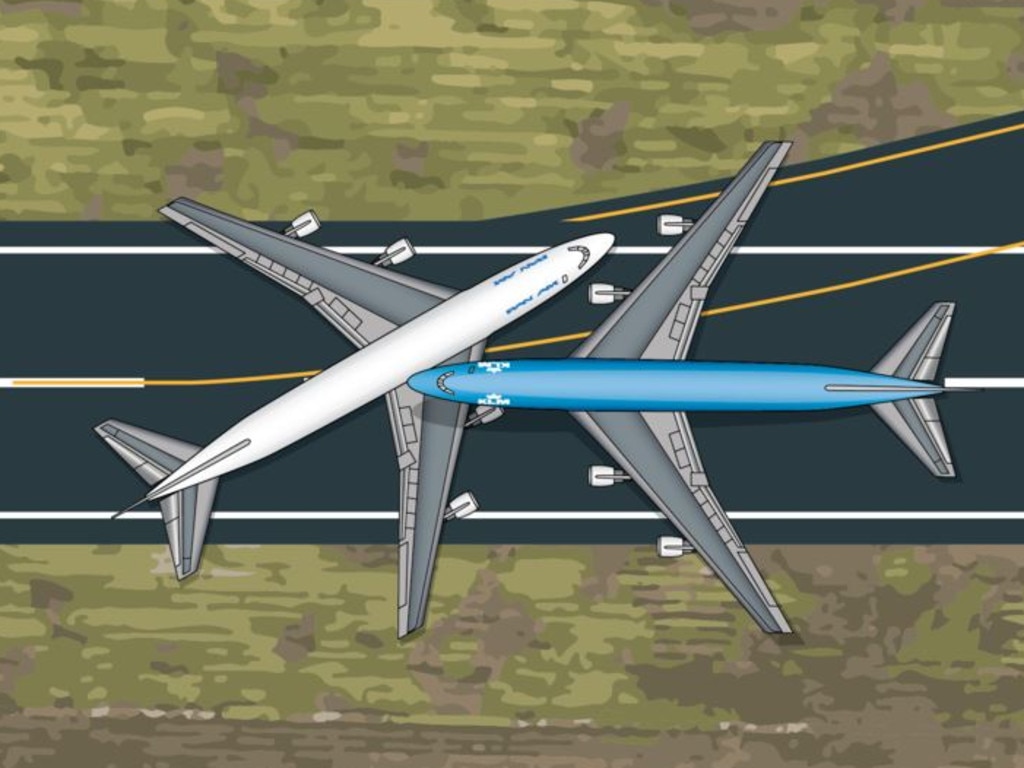

With that, the two mighty jets collided in a catastrophic crash.

The briefly airborne KLM’s undercarriage and engines hit the top of the Pan Am jet, ripping off the top of the fuselage down the centre. The KLM plane stalled, rolled, hit the ground and slid. And with its full fuel load, it erupted into a fireball that blazed for hours.

“When he hit us, it was a very soft boom,” Pan Am co-pilot Robert Bragg, who survived the crash and died in 2017, told the BBC. “I then looked up for the fire control handles and that’s when I noticed the top of the aeroplane was gone.”

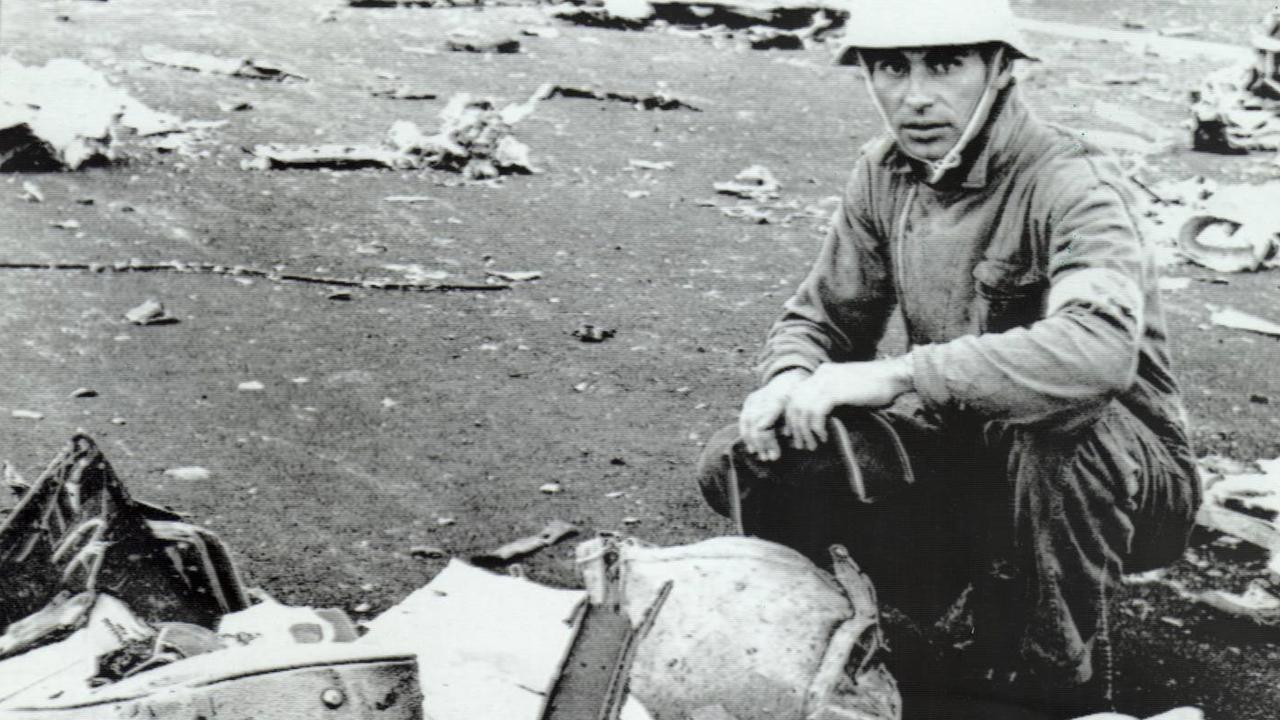

Both planes were destroyed. All 248 KLM passengers and crew died, along with 335 passengers and crew on Pan Am.

There were 61 survivors, all on Pan Am, including captain Victor Grubbs and Robert Bragg.

THE CRASH THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

After an international investigation, the fundamental cause of the crash was deemed to be KLM captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten’s attempt to take off without clearance.

But there were a raft of contributing causes — the fog, the interference of the radio transmissions and use ambiguous phrases, the fact Pan Am had not left the runway, and that the airport was overwhelmed with large aircraft.

The refuelling of KLM, which made the plane heavier and less capable of clearing Pan Am as they were heading for collision — and the fact it fuelled the fire — has also been noted.

But the issue that had lasting consequences for the aviation industry was the misunderstandings between the cockpits and air traffic control.

Part of this was the two-way radio. At one point before KLM took off, air traffic control told the flight deck, “OK, stand by for takeoff, I will call you”. The KLM pilots only heard the word “OK”.

“We believe that nothing after the word ‘OK’ passed the filters of the Dutch crew, thus they believed the controller’s transmission approved their announced action in taking off,” a report into the crash said.

Another factor was use of ambiguous phrases by the pilots. When KLM thought it was ready to take off, the first officer said, “We are now at takeoff”. That phrase wasn’t standard pilot-speak. Neither was “OK”. In the cockpit recordings, the Pan Am pilots spoke English and the KLM pilots spoke Dutch.

The accident led to the development of so-called Aviation English, which is the language used by pilots and air traffic controllers worldwide.

Cockpit rules also changed so words like “OK” and “Roger” were no longer sufficient when accepting messages — key parts of the message now have to be read back in the reply.

These were some of the lessons learnt from the worst aviation accident the world had seen — so it would forever remain the deadliest the world would see.