Aussie tourist destinations turned into ‘no go zones’

The closure of some of the country’s most iconic destinations for cultural heritage reasons has been branded Australia’s “shame”.

The continued closure of some of the country’s most iconic natural environments for Indigenous cultural heritage reasons has been branded Australia’s “shame” by radio host Ben Fordham.

Over the weekend, the 2GB presenter rattled off more than half a dozen iconic landmarks that were now “no go zones” after banning or restricting access in recent years.

In 2019, climbing was banned on Uluru, ending a decades-old tradition for visitors to the Red Centre, in recognition of the rock’s cultural significance to the Anangu people.

But scores of locations around the country, large and small, face similar restrictions.

“We live in the most beautiful country in the world and we’ve just rolled over allowed people to ban us from our own country,” Fordham said on Saturday. “Shame, Australia, shame.”

Kakadu National Park

Speaking Fordham last week, Greig Taylor, owner of Charter North 4WD Safaris, said most of the Northern Territory’s iconic Kakadu National Park was now “locked up for most of the year for reasons given or not”.

“It’s a real problem,” he said.

Mr Taylor said the lack of access to key attractions like Jim Jim Falls, Twin Falls and Gunlom was making almost “impossible” to design itineraries for clients, who were “coming a long way to see what is essentially an international treasure”.

“I’ve been guiding tours in Kakadu for 30 years,” he said.

“I’ve seen the increasing closures, and as a result the decline of tourism. In 1998 annual visitation peaked at around 250,000, it’s currently about 160,000. What we’ve got in Kakadu National Park is a power base that’s basically got a stronghold on the park and they’re not being held accountable. The reasons we’re given often is either environmental reasons, infrastructure upgrades or operational reasons, whatever.”

Cape York Peninsula

Visitors to the northernmost point of the Australian continent, Pajinka, in the Far North Queensland’s Cape York Peninsula, are now required to pay a $10 per person fee at the Jardine River.

The fee was established by agreement between the Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council (NPARC) and the Gudang/Yahaykenu Aboriginal Corporation (GYAC), which has managed the popular tourist destination since 2019.

In 2021, the traditional owners had floated the prospect of closing “The Tip” to visitors altogether after years of “disrespectful” behaviour including graffiti, littering and defecation, although this plan did not eventuate.

GYAC chair Michael Solomon told the ABC at the time that charging a fee would encourage tourists to be more respectful, and that the income would provide long-term benefits.

“If we would have the money, we could have solved a lot of problems with that place, lot of issues and all this stuff,” he said. “If you calculate all the dollars that went past, it could be there up and running — our generation could be walking by now.”

Horizontal Falls

In Western Australia’s Kimberley region, the iconic Horizontal Falls near Broome will be closed to tourist boats by 2028.

The falls, known as Garaan-ngaddim to the Dambimangari traditional owners, consist of two narrow gorges about 300 metres apart, drawing thousands of visitors a year who speed through the rushing seawater on guided tours.

Dozens of people were injured in 2022 when a jet boat crashed into a rock wall at the falls, and the following year the Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation (DAC) announced it would be banning the practice.

In a statement to the ABC at the time, the DAC said Garaan-ngaddim was “mamaa”, or a powerful, sacred place. “Our people lived there all year round and we still feel their presence,” the statement said.

“It is a quiet, calm place but it can be dangerous. You don’t rush through it, we’ve seen how country responds when people don’t respect its power. We ask visitors to be quiet at Garaan-ngaddim, [and] respect our cultural obligations to care for country and culture and keep you safe.”

Finniss River

The popular fishing spot south 75 kilometres southwest of Darwin, known as “Aboriginal sea country”, has been largely closed to recreational fishing since 2023.

The Northern Land Council (NLC), representing traditional owners of the Finniss coastal and Peron Islands Region, first announced in 2021 that it would be limiting access to the private Aboriginal land, and a permit system was introduced in 2023 despite consternation from groups including the Amateur Fishermen’s Association NT (AFANT).

Last year, four people became the first to be charged and fined for fishing without permits in the Finniss River after they were intercepted by rangers past the closure line, the NT News reported.

“It has been exhausting for the traditional owners and rangers, who often come across boats where they shouldn’t be,” NLC deputy chair Calvin Devereaux said in 2024.

“Most of the time the fishers claim to have no knowledge of the closure line, are appreciative of the advice, and generally turn straight around. However, there are always a number of boats who clearly know the area, and just keep coming back.”

St Mary Peak

Hikers in South Australia’s breathtaking Flinders Ranges have long been discouraged from climbing St Mary Peak.

The 1171-metre summit, the highest point of the ranges and the final leg of the Wilpena Pound bushwalk, is considered sacred to the Adnyamathanha people and signs request visitors stay away.

“St Mary Peak is a part of our Muda, which is our creation story of the pound,” traditional owner Rehanna Coulthard told The New Daily in 2019.

“Two serpents came down here and ate a lot of our ancestors. St Mary Peak is actually the head of one of the serpents.

“It is quite saddening [when visitors climb the peak], because when we go to other countries and visit places and they say, ‘You can’t climb the Taj Mahal’, or, ‘You can’t go and pick a piece out of the Sistine Chapel’, we respect that.

“We hope our visitors do come here, go as far as the Tanderra saddle, but just not climb the peak of St Mary, because it is quite a sacred site for Adnyamathanha people.”

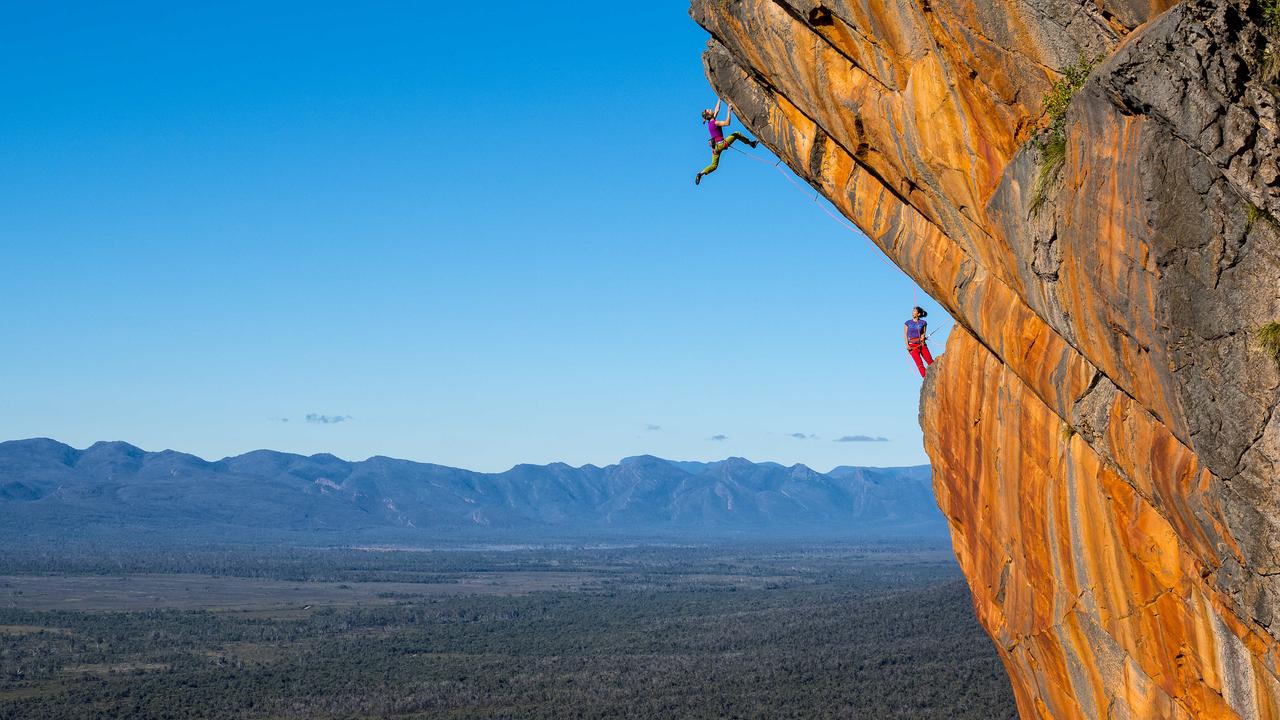

The Grampians

Rock climbing, walking and camping were banned in large parts of Victoria’s Grampians National Park, 250 kilometres from Melbourne, in 2019 in order to preserve Indigenous cultural heritage including rock art.

Breaches of the Aboriginal Heritage Act can attract fines of up to $346,000.

The ban covers about one third of the park, which contains 90 per cent of Victoria’s rock art sites and is owned by three traditional owner groups — the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owner Aboriginal Corporation (GMTOAC), Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation (EMAC) and Barengi Gadjin Land Council (BGLC).

The Australian Climbing Association of Victoria, which formed in response to the ban, launched an ongoing campaign to roll back the measures. It said the “unprecedented” ban, covering nearly 80 per cent of existing routes, was a “blunt and lazy way” to protect cultural sites.

But EMAC chairman Jason Mifsud said the “preservation and protection of Aboriginal cultural heritage is non-negotiable”. “We aren’t saying that there’s to be no climbing, what we are saying is that there is to be no further destruction of cultural heritage,” he told The Guardian.

Mount Gillen

Hiking to the top of Alice Springs’ Mount Gillen, known as Alhekulyele, has been banned since 2021 at the request of the Mparntwe traditional owners.

The steep walking track, though unauthorised and unsignposted, was a popular attraction for locals and tourists alike, offering sweeping views of the desert capital.

The Northern Territory government said at the time that “after many years working to explore alternative, safe routes, it has been decided that closing access is the only option”, with fines of up to $31,600 now in place.

Benedict Stevens, traditional custodian and spokesman for the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (AAPA), said the site was “central to Ayeye Akngwelye Mpartnwe-arenyethe — Dog Story of Alice Springs” and the climbing track “never should have been there”.

Traditional custodian Doris Stuart told the ABC at the time that she felt physical pain when she knew people were walking up the ridge.

“I can’t look that way towards where that [path] has been created by man,” she said. “It’s like I’ve been scarred and that my rib cage has had the knife run across it.”

Lake Eyre

Lake Eyre in South Australia, now known as Lake Eyre/Kati Thanda, is a 9500 square kilometre dry lake bed famous for infrequent and spectacular flooding.

But under a new management plan enacted by the Arabana traditional owners last month, tourists will no longer be able to walk on the lake — largely for “public safety” reasons, according to National Parks and Wildlife Service SA.

Other recreational activities, including swimming, driving, boating and landing aircraft, were already restricted under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.

Bronwyn Dodd, chairwoman of the Arabana Aboriginal Corporation, said last year the lake was a very special place of cultural significance and great importance to the Arabana people.

“We are proud to share this part of our Country but we urge you to respect our Ularaka [stories], lore and culture and not enter the lake,” Ms Dodd said.

“We have a responsibility to look after the lake and in turn it looks after us. Preservation of this lake is also the preservation of our culture.”

Mount Warning

In NSW, the years-long closure of Mount Warning in the Northern Rivers region’s Wollumbin National Park has been a long-simmering controversy.

The breathtaking mountain, which once attracted more than 100,000 people a year, was initially closed to the public amid Covid restrictions in 2020 and in 2021, the local Aboriginal owners requested the track be closed permanently.

The Wollumbin Aboriginal Place Management plan stated that the mountain was considered a “men’s site” and that its “sanctity … may also manifest physically”, making people sick or putting women in “physical danger”.

“For example, if women access areas that are restricted to men, women are in physical danger and likewise for men,” the plan stated.

The closure sparked protests as some people defied the ban to climb the peak. It was revealed last year that the private security guards had been hired to the tune of $7000 per week to keep people away from the mountain.

Speaking to NSW Premier Chris Minns last week, Fordham again raised the issue of Mount Warning, arguing it “doesn’t sit with your approach” of pushing back against opposition to concerts at Moore Park or UFC events.

“So when you’ve got a handful of people saying we don’t want you going to Mount Warning, but 127,000 people a year who want to go there, surely the majority should get a say,” Fordham argued.