New plans for creepy abandoned Aussie ‘lunatic asylum’

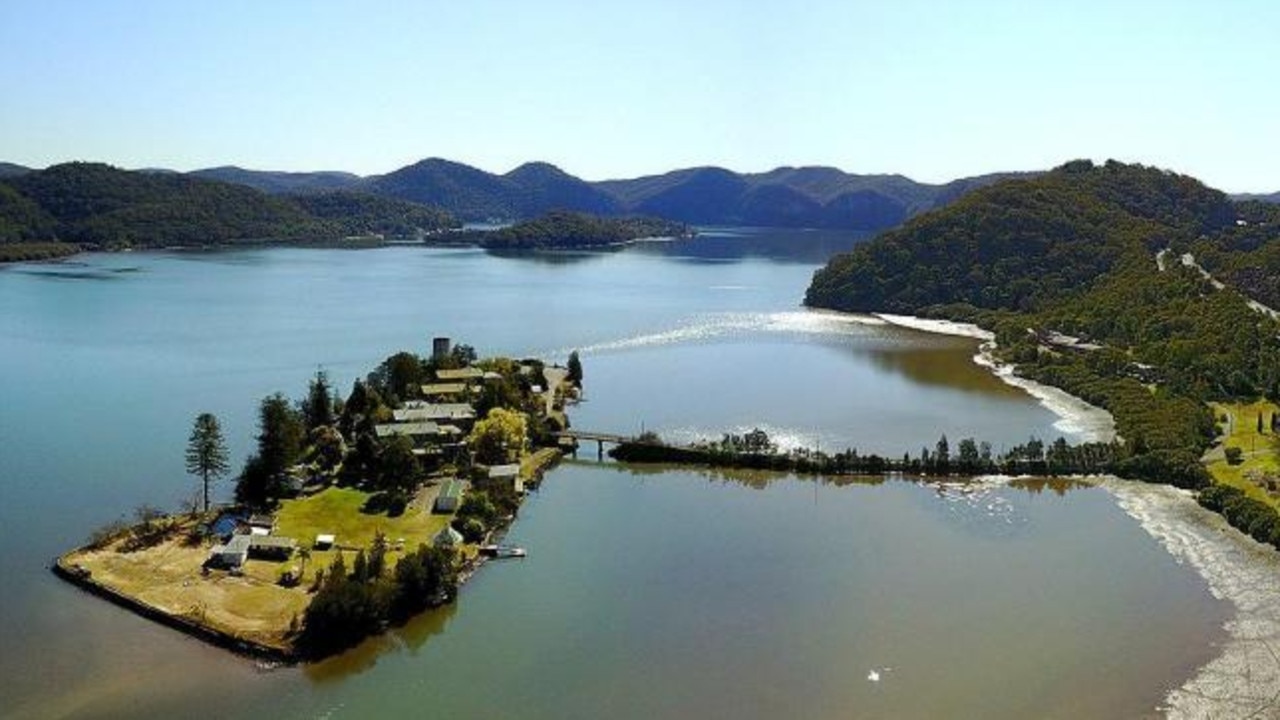

If you’ve ever driven north of Sydney on the M1 and looked left as you cross the Hawkesbury River Bridge, you may have noticed an unassuming looking island.

If you’ve ever driven north of Sydney on the M1 and looked left as you cross the Hawkesbury River Bridge, you may have noticed an unassuming looking eight-hectare island. While it may look peaceful now, it has an incredibly dark past.

Peat Island was established as an asylum for “inebriates” in 1911 before it was reopened as a psychiatric hospital, just 50km north of Sydney.

If the walls could talk they would tell of the horrors experienced by patients, including children, on a site plagued by death and despair.

Both media and government departments reported torture, multiple drownings and unexplained deaths of men and little boys.

According to reports, ‘Ward 4’, was where the most brutal treatment took place.

The first major incident recorded was in 1924 when William Pfingst admitted to killing another inmate, Harold Besley, by hitting him with a stick, tying him up with a bag over his head before dropping him in the water where he eventually drowned.

The mysterious deaths of child patients repeatedly made headlines over the years of the facility’s operation.

Among them was the case of Robert Bruce Walker, 8, who was found floating off the island after he had been ‘put in the pen’, a caged compartment, as punishment, in 1940.

The hospital manager, William James McCoy told an inquest into the boy’s death that “these patients are up to all sorts of tricks”.

In May 1950, 11-year-old Robert Blackwood was found asphyxiated in a linen bin made of iron after only five months at the institution.

A hospital attendant said Robert had been ‘mischievous and playful’ and had died playing ‘hide and seek’ among a pile of soiled linen.

One journalist, who visited the island in 1956, described it as a ‘hospital of forgotten children’.

Many other unexplained deaths also took place on the island.

At least 300 patients who died at the institution were buried in unmarked graves at the nearby Brooklyn Cemetery.

Reports of sexual and physical abuse, torture and a lack of thorough investigations also spilt out from under the closed doors of the site.

Dr Ted Freeman, who worked at the mental institution for one year in 1981, described Ward 4 as ‘a prison’.

“In January 1981, I met with the Medical Superintendent of Peat Island and walked around the wards with him,” Dr Freeman wrote in his book Battle for the Injured Brain, co-authored by Dr Peter Cullagh.

“There were approximately 160 patients, or residents as they were called. Some had been inmates for almost 50 years.

“The staff were caring but it was a custodial institution. Many of the wards had an open-door policy. One ward did not. It was Ward 4.

“Its doors were heavily padlocked and the windows had heavy wire mesh over them. It was a prison.

“The smell of human urine, faeces and vomit hit you the moment you entered.

“The patients were shouting, screaming, yelling, banging their heads, jostling each other, walking or dragging themselves from one place to another apparently without purpose.

“Many had adopted the typical institutional constant rocking movement — backwards and forwards — whether standing, sitting or lying on the seats or on the floor.

“Some were openly aggressive. It was One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest in reality.”

Dr Freedman said the staff were caring and he never saw any of them abuse any patients.

“I researched the medical records of each patient in Ward Four,” Dr Freeman said.

“One-third of admissions were post encephalitis, often from measles; one-third were admitted because of cerebral palsy.

“No information was recorded about the other inmates. I noted many records on incidental things such as skin rash or ingrowing toenails or haemorrhoids but only minor entries detailing the brain injury or the mental state or behaviour of the inmates. The data were very unbalanced. The clinical notes indicated no therapy had been given even on a trial basis in Ward Four. The residents in this ward were there forever.

“For them, death was the only release.”

The psychiatric hospital later became a residential care centre for people with intellectual disabilities who were reportedly kindly cared for following the brutal regime, before the last patient left in 2010.

Today, the original Edwardian period buildings — including the hospital, patient housing, a large water tower that had water pumped across from the mainland and a car park — sit rusting and overgrown, surrounded by water and nestled in the shadows of tree-covered hills.

The only way to reach the island is by boat or over a causeway but access is forbidden to the general public.

Rabbits have again inhabited the land, once known as Rabbit Island in 1841, before construction on the Peat Island facility started.

New future

In 2018 it was reported that the site would become a “tourist hub” with holiday units, a foreshore walk and 130-berth marina.

But in 2022 the land was transferred back to the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council, following an eight-year process and 10 months of intense negotiations.

The DLALC Chairperson Barry ‘BJ’ Duncan said he looked forward to the island ultimately being transformed into a site everyone can be proud of.

“Kooroowall-Undi has languished for too long, and we have many possibilities that we’ll workshop with our Members, on an economically-productive and culturally-appropriate future for the island.

“Our plans will of course be focused on Aboriginal employment, business development and economic growth,” he said.

Duncan said the experiences of former residents must also be acknowledged.

“The Peat Island history over the last century or so isn’t only about sorrow, it’s about resilience. We want to do justice to the strength of the ex-residents and staff of the former facility. Acknowledging their experiences with respect, will also assist with the island’s deep spirit into the future,” he said.

The island is home to the Darkinjung people and its traditional name Kooroowall-Undi means “Place of the Bandicoots”. It sits in one of the most beautiful vistas along Deerubbin and is part of the birthplace of the extensive Baiame Creation story, which begins at the back of the Central Coast.

DLALC CEO Brendan Moyle says the area is steeped in cultural significance, and its ancient culture and lore should be celebrated at national and international levels.

“Too often, tourists from around Australia and the world bypass the NSW East Coast to learn more about ancient Aboriginal Dreaming stories and practices across Northern Australia. This transfer now opens an opportunity to create a place where we can showcase ancient and contemporary Darkinjung culture for everyone to enjoy,” he said.

- with Megan Palin at news.com.au

This article originally appeared on Escape and was reproduced with permission