Inside the deadly cocaine business moving drugs from Peru to Australia

Armed backpackers are joining a dangerous hike that’s the first step in a bloody mission to get millions of dollars of drugs to places like Australia.

In the dead of night, backpackers carrying rifles and grenades meet up in the Peruvian jungle for the beginning of a 5000km journey that could cost them their lives.

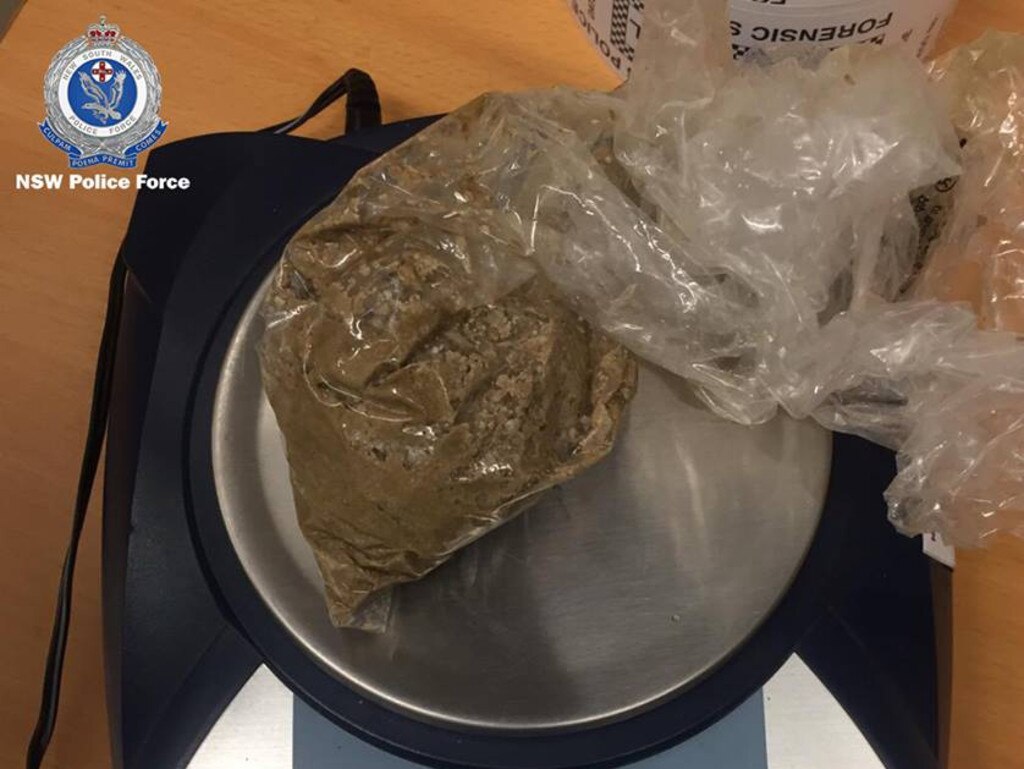

Between them, the young men are carrying 30kg of cocaine paste – which will eventually be worth $A973,000 by the time it reaches users.

The dark and dangerous hike is the very first step in a supply chain that will see their paste smuggled to all corners of the world, from Miami to Melbourne.

And even at this stage, the traffickers are risking their lives transporting their illicit cargo – which some start doing when they’re just 15.

“Everyone involved in this kind of business is armed,” one of the backpackers tells journalist Mariana van Zeller in the latest episode of a new National Geographic series called Trafficked.

Van Zeller asks the smuggler what would happen if they’re ambushed as they hike over the mountains.

“It would be war. Blood would flow. To save your life, you shoot your enemies,” he tells her.

This is every day life on the brutal cocaine highway – which sees millions of dollars of cocaine secretly smuggled from the mountains of Peru to users’ bloodstreams every day.

HIDDEN LABS DEEP IN THE JUNGLE

Many cocaine users probably don’t think about where the drug comes from – but in Peru, countless families’ daily bread depends on the trade.

In the extremely poor Valley of the Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro Rivers (VRAEM), around a fifth of the world’s cocaine is produced in jungle labs.

“I’m not proud of it, but we’re one of the best producers of cocaine because of the abundance of coca leaves, which is raw material to make the product,” Mariana’s local contact Ceviche tells her.

It’s not illegal to grow and sell coca leaves in Peru, and farmers depend on the sale of the crop to feed their families.

But processing the leaves into cocaine is illegal – meaning the vast trade is controlled by violent criminal organisations.

A revolutionary communist group, the Shining Path, extorts growers for protection money and charges traffickers to use the smuggling routes which the Path controls.

Under the cover of darkness, van Zeller visits a lab to see the grim process by which coca leaves becomes one of the most addictive drugs in the world.

Over 400kg of coca leaves are soaked in a pit of water, acid and bleach for days just to make a single kilogram of cocaine.

Cement and gasoline are added into the toxic brew before ammonia is used to make the drug into solid bricks.

From there, groups of “mochileros” – Spanish for “backpackers” – carry the bricks over the Peruvian mountains on foot to avoid police road blocks.

One of the backpackers tells van Zeller that one ambush from thieves cost the lives of three of his friends, who were all aged around 19.

It’s a hard life filled with danger, but it’s also one of the only options to earn decent money in the region.

Van Zeller hears from one young smuggler that he is going to leave the trade to study to become a dentist.

“Sometimes I’d see the ads on TV, you know, with the smiles,” he says.

“You want your teeth to look like that, you know? That is my dream.”

‘IT WILL BE CERTAIN DEATH’

As the cocaine changes hands, its cash value increases – as do the risks involved in smuggling it.

From the backpackers, it’s driven to the Peruvian capital Lima, before being smuggled through Ecuador into Colombia.

There, it arrives in the port of Turbo, where it’s loaded into fishermen’s boats to be smuggled into the US.

“People say that life in Turbo is partying, it’s having sex,” local fixer Oliver Schmieg tells van Zeller.

“You drink hard, you party hard, and you know soon you might be a dead man out on the streets. Because nearly everyone here earns a living in a dangerous world.”

The danger is known all too well by the smugglers, who pose as fishermen to traffic cocaine.

“Sometimes you get in trouble with the owner of the merchandise and you can even be killed,” one smuggler says of the Colombian Gulf Clan, which runs the local coke trade.

“You don’t mess with those people. It will be certain death.”

Described as a “super cartel”, the Gulf Clan is headed by the notorious Otoniel – a kingpin infamous for assassinating government officials and thought to be behind a grenade attack on a nightclub.

Even high ranking cartel members below him, who control as many as 300 men, could be executed for trivial missteps.

Knowing that taking part in an interview could cost him his life, one commander involved in moving 1000kg of cocaine worth more than $42 million a week tells van Zeller why he’s speaking out.

“I have a daughter who’s four years old. We want to see our children grow up,” he says.

“We want a free life. A life free from the danger of the government, free from the danger of your own people killing you.”

WAGING AN UNWINNABLE WAR

Half of the cocaine that leaves Colombia goes to Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia – but the other half goes to the US alone.

The sheer scale of the number of illicit shipments gives the US Coast Guard an impossible task in stopping the drugs flooding in.

“We’re operating in an area (of water) larger than the continental United States,” one Coast Guard employee tells van Zeller.

“Now imagine you have three or four police cars patrolling the United States.

“That’s essentially what the Coast Guard, with our ships, is doing.”

Smugglers make the Coast Guard’s job even harder by using small boats with fibreglass hulls, which are difficult to detect on radar, or even specially made narco subs.

Once it arrives in Miami, the cocaine is sold by the ounce to dealers who in turn, sell it to users in small amounts.

One dealer, who carries a .357 Magnum for protection, says he’ll sell $2600 of cocaine for $6500 in three days – making $1300 a day.

“The product sells itself,” he says.

With such incredible global demand for cocaine, the dealers, traffickers and growers continually expand the trade, despite dogged efforts of law enforcement around the world.

In 2020, the EU drugs agency said cocaine purity levels were at their highest ever recorded, coupled with an unprecedented availability in Europe.

And the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction found that more young people in the UK took cocaine than anywhere else in Europe.

But the insatiable demand for cocaine isn’t confined to Europe – it’s global.

“Cocaine will never end. Never, it will never end,” one Colombian smuggler tells Mariana.

“It ends if the world ends. It’s the only way.”

This article originally appeared on The Sun and was reproduced with permission