Detail buried in Pompeii reveals chilling truth about humans

A secret room buried in the rubble of the ancient city of Pompeii has shed light on something humans have never known before.

A shrine. A banquet hall. Graffiti. The buried city of Pompeii is revealing the deepest secrets of ancient Roman life as archaeologists rush to save the ruins from rotting.

The city represent a moment frozen in time.

That time is 79AD. Pompeii was a bustling Roman port on the Bay of Naples and a centre of commerce and culture.

The moment is August 24, when its residents rushed to flee an eruption of the neighbouring volcano, Vesuvius.

“Pompeii is truly a treasure chest that never ceases to surprise us and arouse amazement because, every time we dig, we find something beautiful and significant,” says Italy’s Minister of Culture, Gennaro Sangiuliano.

Over the centuries, about two-thirds of the city has been uncovered from volcanic ash. This includes harbour facilities, cobblestoned highways, mosaic footpaths, fast-food shops, ornate temples – and elaborate mansions.

But the excavations of Pompeii’s Regio IX neighbourhood are being propelled by the need to head off water damage as moisture leeches into the soil from nearby housing developments.

It’s a vast effort.

It’s believed the neighbourhood still contains the remains of 1070 Roman homes, with more than 13,000 rooms waiting to be excavated.

Recent discoveries offer a taste of what is yet to come.

A bakery. A laundry. Service rooms. These offer an unprecedented look at the often overlooked lives of everyday citizens.

But there’s also plenty of grandeur and luxury for which the Roman civilisation is renowned.

This is amply evident in one focus of ongoing excavations – two interconnected villas just off one of Pompeii’s main roads.

One new find is a brilliantly coloured family shrine. In contrast, one of the villa’s servant’s quarters has also been uncovered.

And archaeologists have unearthed a private banquet hall decorated with frescoes of scenes from the famous poet Homer’s account of the Trojan War. There, servants scrawled on the walls what was topmost on their minds.

Sacrarium

The most recent discovery announcement describes a small room painted in a brilliant shade of sky blue.

This colour was rare in antiquity because of the difficulty in sourcing materials to produce the pigment. So its use was generally reserved for places of religious or political significance.

This room is no exception.

Its understated frescoes are described as among Pompeii’s most subtle and refined.

Embellished golden lines of lacework section the brilliant azure background. Ornate architectural structures provide a visual frame. And neatly spaced around the room are images of female demigods, each representing a season or pastoral activity.

Excavators say the 8sq m room was likely a sacrarium – essentially a household shrine for family rituals and to store sacred objects.

Niches in each wall – each highlighted in red – were intended to hold statuettes. But the room is unlikely to have been used for its intended purpose.

The villa around it was in the late stages of renovation work.

Large clay amphorae were stacked against one wall with bronze jugs and lamps. Piles of building materials were spaced about its mosaic floor – including a mound of oyster shells (which would have been crushed up and used as a binding agent for plaster).

While the sacrarium reveals the extent of luxury enjoyed by Pompeiians at the top end of town, excavators have also uncovered the quarters occupied by one or more of the family’s servants.

Attached to the previously excavated Civita Giuliana villa is a simple room. There are no frescoes or plastered walls. Instead, it’s a basic structure of earthen floors, rough stone walls and basic timber furnishings.

The shapes of these perished objects have been captured in plaster casts.

The timber – enveloped by volcanic ash – has long since rotted away. But the ash had set firm, leaving a void where these items of everyday life had once been.

There’s minimal furniture. Just a collapsed bed and a square frame leaning against one wall.

But the room is filled with tools, including buckets, baskets, a saw, coiled rope and pieces of timber.

Banquet hall

Paris. Helen. Apollo. Cassandra. The tales of these mythological superheroes still fascinate – and feature in modern storytelling.

Their enduring popularity is highlighted by well-preserved frescoes in what archaeologists describe as a private banquet hall.

The 15m by 6m room has a bright white mosaic tile floor with dramatic black walls.

“The walls were painted black to prevent the smoke from the oil lamps being seen on the walls,” says Pompeii Archaeological Park director Gabriel Zuchtriegel

And the flickering lamps would have brought the bright-coloured frescoes to life.

“People would meet to dine after sunset. The flickering light of the lamps had the effect of making the images appear to move, especially after a few glasses of good Campanian wine,” he adds.

One shows the Trojan prince Paris meeting the Spartan queen Helen. Their romance (some say abduction) triggered the 10-year war to recover her.

Another shows the god Apollo using a lyre in an attempt to seduce the Trojan princess Cassandra.

“They refer to the relationship between the individual and fate: Cassandra, who can see the future, but no one believes her; Apollo, who sides with the Trojans against the Greek invaders, but being a god, cannot ensure victory,” says Zuchtriegel. “Helen and Paris who, despite their politically incorrect love affair, are the cause of the war – or perhaps merely a pretext.”

The hall opens onto a courtyard. And nearby is a service room with a simple staircase leading up to a second storey. Beneath the staircase is another clutter of building materials.

What occupied the staff as society’s finest danced and dined nearby can be found on the walls of the stairs’ archway.

There, scrawled charcoal graffiti depicts fighting gladiators and a stylised penis.

Naughty children

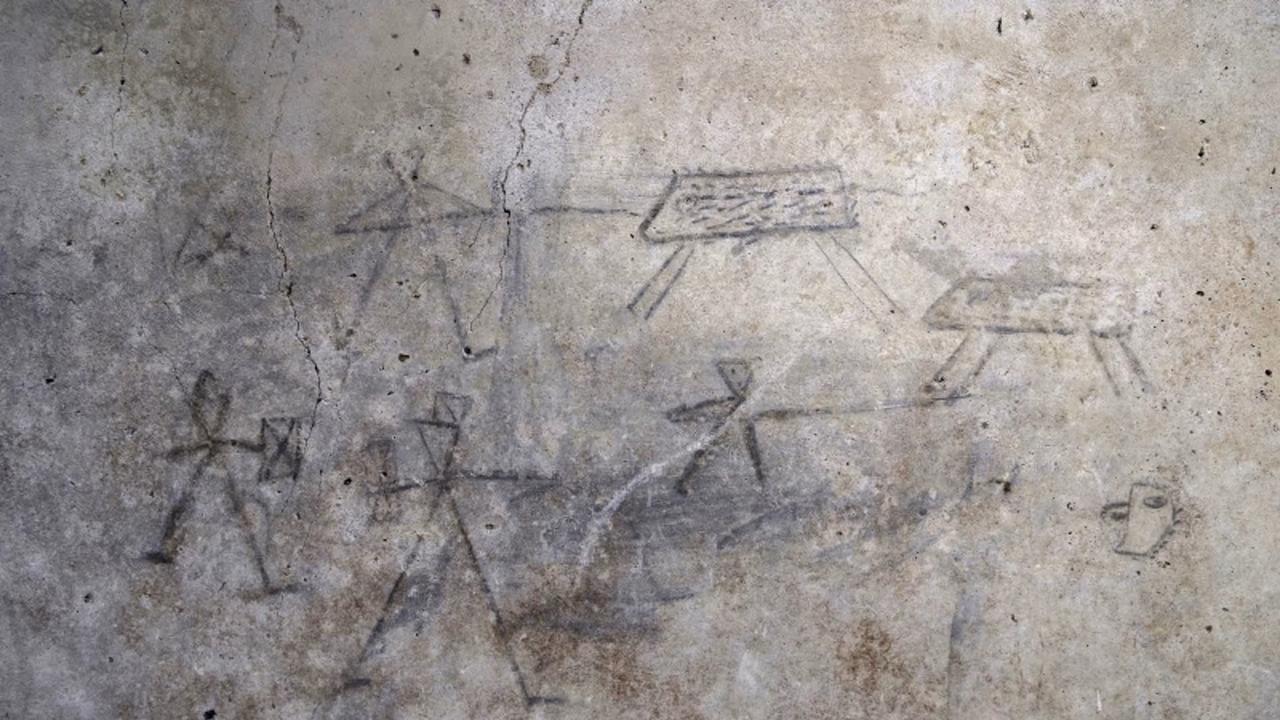

Gladiators are also featured in charcoal graffiti, which archaeologists attribute to children.

These scrawled images appear along a wall leading to a courtyard where they could play away from the busy streets.

Here, several stick-figure armed men are shown clashing with wild beasts. Nearby is an image of two figures playing with a ball, and another of what may be two boxers or wrestlers lying on the ground.

“Together with psychologists from the University of Naples, we have come to the conclusion that the drawings of gladiators and hunters were made based on a direct vision and not of pictorial models,” says Zuchtriegel.

“Probably one or more of the children who played in this courtyard, among the kitchens, latrine and flowerbeds for growing vegetables, had witnessed fights in the amphitheatre, thus coming into contact with an extreme form of spectacularised violence, which could also include executions of criminals and slaves.”

Nearby, bodies were found in the doorway of an unpainted room.

Archaeologists speculate that the two-villa complex – including the banquet hall, shrine, laundry, and bakery – was nearing the end of major renovation work.

More Coverage

Only a few rooms needed finishing – and the workers’ tools and leftovers needed cleaning up.

“Everything brings us back to an everyday dimension that had rhythms in some ways very similar to our own modern lives,” says Pompeii archaeologist Dr Ausilia Trapani. “When you find the remains of a person, it’s like seeing yourself again, and what you’re made of: Your bones, but also your fear of death and the hope of an afterlife.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel