‘Potential clue’: Scientists reveal major breakthrough in case of missing MH370

Could a humble barnacle hold the final piece in the puzzle surrounding the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 in 2014?

Could a humble barnacle hold the final piece in the puzzle surrounding the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 in 2014?

The answer is elementary. Oxygen isotope elementary.

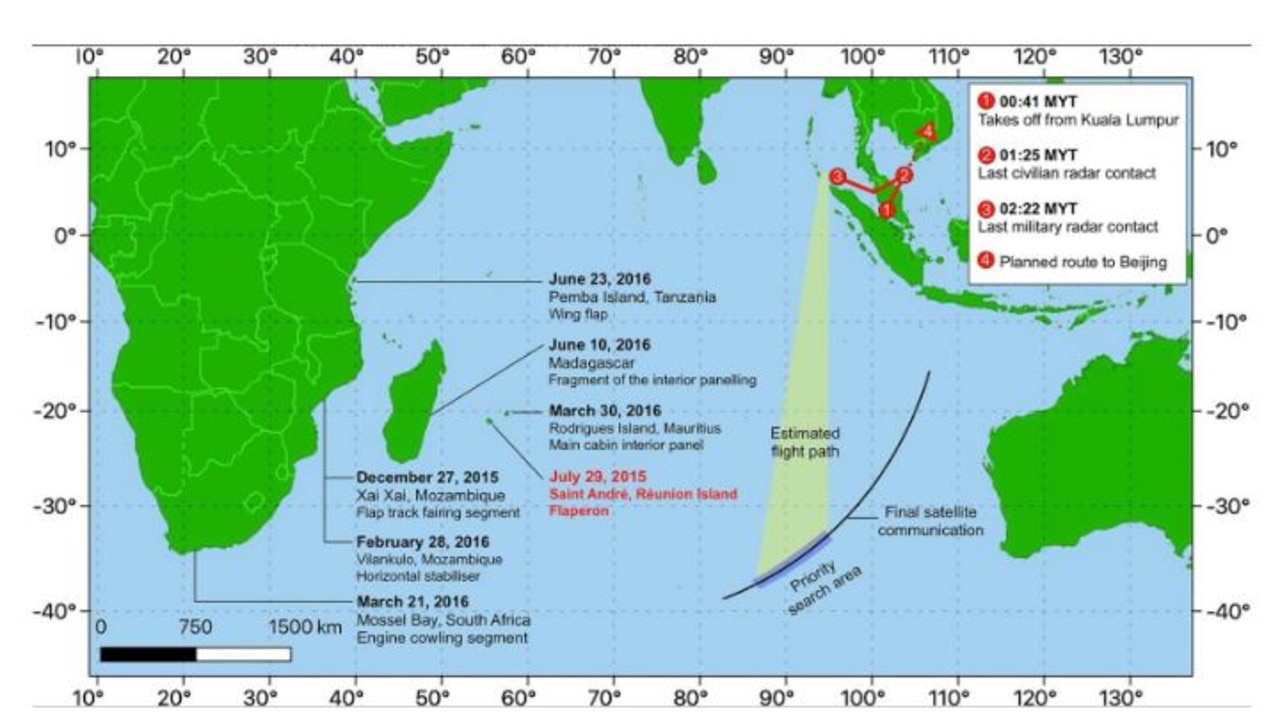

In 2015, a year after the Boeing 777 carrying 239 passengers disappeared, the first pieces of aircraft debris began washing up on the French Reunion Island. Barnacles were observed growing on a 2.5m section of wing control surface known as a flaperon.

“I knew the geochemistry of their shells could provide clues to the crash location,” said University of South Florida geoscientist associate professor Gregory Herbert.

It’s not the first time the crustacean has been suggested as a potential clue.

“Barnacle shells … can tell us valuable information about the water conditions under which they were formed,” then-Griffith University PhD student Ryan Pearson told media at the time.

He had been studying how the growth patterns and chemical makeup of shells could be used to extrapolate the migratory patterns of loggerhead turtles.

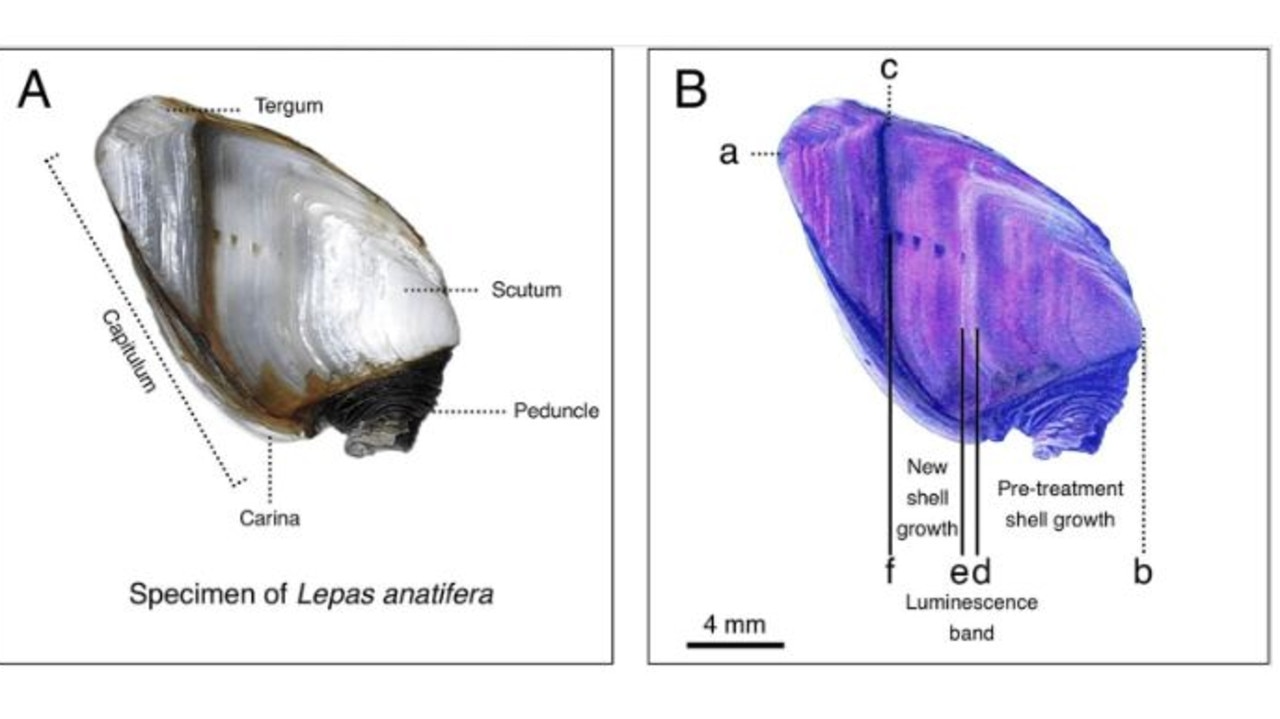

Temperature and water quality influence their growth on a daily basis. This could potentially be “read” in a similar way to tree rings. However, the understanding necessary to extract this information was only emerging at the time.

Now, Australian senior government oceanographer David Griffin has told National Geographic that new research was “an important step towards possibly satisfying Malaysia’s requirement for ‘credible new evidence’ to restart the search.”.

“We knew there were clues encrypted in the shells of the barnacles, but the problem was that no one really knew how to decode them,” he explained.

“That’s what this group has done. They’ve given us the methods to decode the data that’s there – stored in barnacle shells.”

Elementary evidence

Like Pearson, Herbert says 2015 photos of the barnacle-encrusted MH370 flaperon were his inspiration.

He’s been working on refining methods to extract useful data from the oxygen isotopes in shell growth layers for the past decade. The study, published in the American Geophysical Union journal Advances, details how the shells “record” the temperatures they have been exposed to.

Shelled marine life add new layers to their shells each day.

And the chemistry influencing the oxygen isotopes trapped in each layer is determined by the temperature of the surrounding water.

Herbert’s research team has conducted growth experiments with live barnacles to track and record the changes to this chemistry and create a “codebook” to read the histories of other crustaceans.

This technique has been used to determine the age of endangered giant horse conches. And it has helped assess environmental conditions at the time of the disappearance of the Jamestown colony – the first attempt to establish a permanent English settlement in North America.

Herbert argues that barnacles found on MH370 debris would also have recorded the temperatures they were exposed to.

These can be compared against water temperature records from the time. When run through an oceanographic simulation, it could produce a potential drift pattern leading back to the crash site.

Trail of breadcrumbs

There’s never been much to go on in the hunt for MH370.

The Boeing 777’s radar transponders and communications systems were somehow shut down shortly after it took off. This can only have been a co-ordinated, premeditated act.

Specifically, it meant nobody could “see” where the aircraft was once outside ground-based radar range.

But the saboteurs were unaware of one thing.

Malaysian Airlines may not have paid the subscription fee to receive automatically transmitted data from the aircraft’s engine monitoring systems. But the on-board modems still transmitted hourly “handshake” signals to satellites to check-in.

One of these satellites, the Inmarsat 3F1, was positioned above the Indian Ocean.

It recorded seven “handshakes” from MH370, revealing how long it had remained aloft. But the precise timing of the signal also allowed investigators to judge how far from the satellite the aircraft was. And minuscule distortions in the transmission – Doppler shift – showed whether it was flying towards or away from it.

When plotted on the globe of the Earth, that hourly data produced an arc. The Boeing 777 must have been somewhere along a given line each time the signal was received.

These arcs were further reduced through simple mathematics accommodating how far the aircraft could have flown at various speeds between each ping.

But, as there were seven such arcs to plot, the range of possible courses grew exponentially.

Tracks over land could be eliminated. As could those passing through radar envelopes.

Professor Martin Kristensen, an engineer at Aarhus University in Denmark, published a mathematical analysis of MH370’s radar and satellite data in 2019.

It calculated the most probable locations where the boundaries of fuel, speed, “handshake” arcs and Doppler shift overlapped.

It found Australia’s primary search area between Perth and Antarctica had correctly identified one of two points of highest probability. The second was much further north – in the warm waters southwest of Australia’s Christmas Island off the south coast of Indonesia.

This area is yet to be searched.

Access to evidence

“French scientist Joseph Poupin, who was one of the first biologists to examine the flaperon, concluded that the largest barnacles attached were possibly old enough to have colonised on the wreckage very shortly after the crash and very close to the actual crash location where the plane is now,” Herbert said.

“If so, the temperatures recorded in those shells could help investigators narrow their search.”

However, the University of South Florida researchers have only been able to extrapolate a short drift trail based on the young age of barnacles made available from the MH370 debris. Now, they want access to those believed to have been up to a year old at the time of their recovery.

The earliest chemical fingerprints in the oldest barnacles could reveal the water temperature near the crash site. This could help narrow down where debris originated on the final satellite signal arc.

If it was cold water, MH370 might have been near the 4,500,000km2 searched after the crash.

If it was warm water, the hunt may have to shift much further north towards Christmas Island.

“Sadly, the largest and oldest barnacles have not yet been made available for research,” Herbert said.

“But, with this study, we’ve proven this method can be applied to a barnacle that colonised on the debris shortly after the crash to reconstruct a complete drift path back to the crash origin.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel