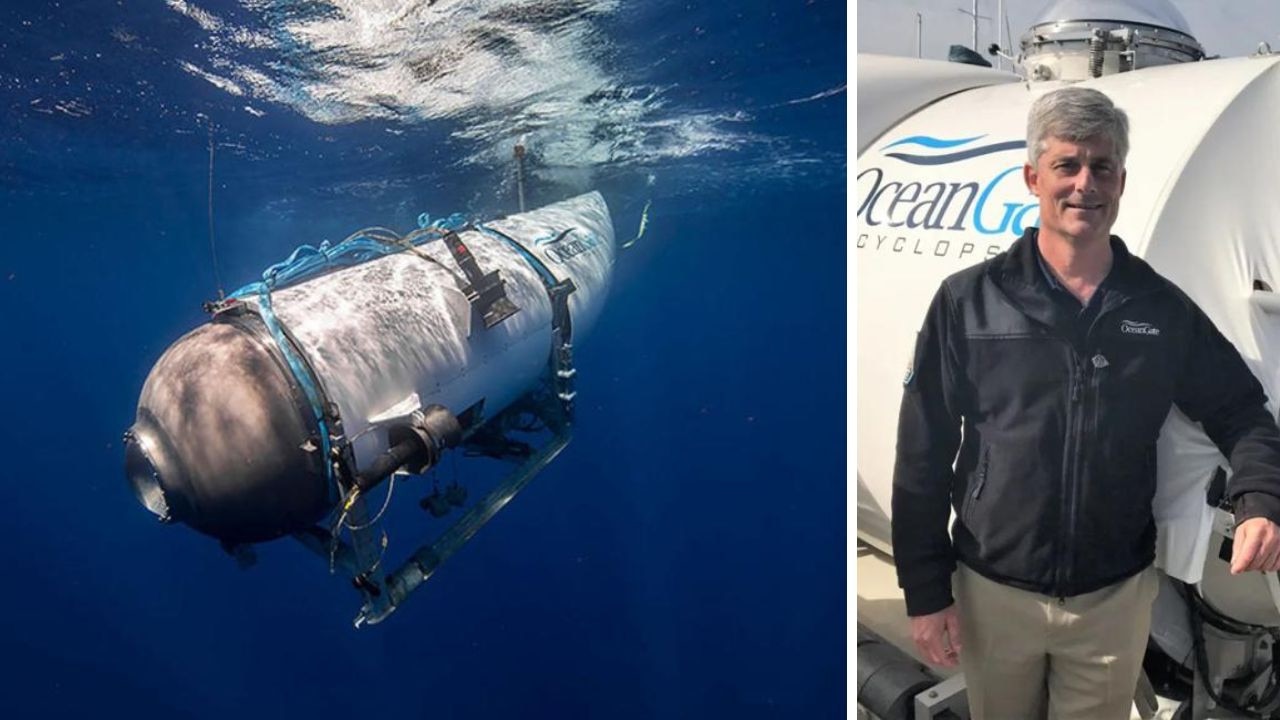

’Overwhelmingly complex’ task facing desperate sub rescue mission

There are three possible scenarios facing the trapped passengers of the missing sub. And the odds of surviving any one of them are grim.

Are they bobbing on the surface of the Atlantic, bolted into a tiny titanium coffin?

Are they freezing in the dark, being pushed around by subsurface currents?

Or are they stuck in the mud amid the 111-year-old wreckage of the SS Titanic?

These are the three scenarios facing rescuers racing to save the researchers, multi-millionaire tourists and the CEO of the missing submersible before their air runs out tomorrow.

The odds of surviving any one of these situations are infinitesimally small.

But only if they’ve not already been crushed to death under 380kg pressing down on every square centimetre.

So far, the missing mini-van-sized submersible and its five passengers have yet to be found.

And that in itself is an overwhelmingly complex task in the vast expanse – and depths – of the North Atlantic.

The fact it hasn’t called for help is another ominous sign. At best, it means the battery-operated communications system has failed. It could also mean the entire power grid has gone down – shutting down everything from the craft’s drive system to its internal heaters.

“In a best-case scenario, the Titan may have lost power and will have an in-built safety system that will help it return to the surface,” University of Sydney professor of marine robotics Stefan Williams writes.

“Alternatively, the vessel may have lost power and ended up at the bottom of the ocean. This would be a more problematic outcome.”

On the surface

Submersibles like Titan usually carry ballast weights. These are designed to counteract the buoyancy of the air contained within the pressurised hull.

That’s how they sink – in a controlled manner – to the ocean’s floor.

In an emergency, these weights are typically released. That allows the craft’s natural buoyancy to carry it back to the surface.

This is the best-case scenario facing rescuers.

“You don’t have to worry about bends or anything like that because they’re in normal air pressure,” says maritime historian Sal Mercogliano.

But the rest of the circumstances are not all that great.

The Titan is just 6.7m long. It’s made of carbon fibre and titanium. And its white-painted hull would be bobbing among the Atlantic’s whitecaps.

The retired Royal Australian Navy Rear Admiral Chris Parry told Sky News that if this was the case, it “would have been found by now”.

That’s because US and Canadian military and coast guard aircraft have been scouring the surface since the alarm was first raised on Monday morning Australian time. Radar, thermal imaging and human eyeballs have already covered tens of thousands of square kilometres in the hope of spotting the vessel.

And its passengers would still be running out of air.

They’ve been bolted in from the outside. The submersible’s hatch is secured against the immense pressures experienced 3.8km below the surface by 17 reinforced bolts.

And the only way to remove them is from the outside.

Underwater

“Another possibility is that there may have been a fire on-board, such as from an electrical short circuit,” writes Williams.

“This could compromise the vehicle’s electronic systems, which are used for navigation and control of the vessel.”

Everything about the Titan is electric and powered by on-board batteries.

And its sole control system is purported to have been a wireless handheld game console controller, which takes batteries too.

The submersible is driven by two electric thrusters capable of pushing it through the water at 3 knots (5.6km/h).

If the electrical distribution system is upset or the batteries fail, there may be no means to control the submersible.

And if that includes being unable to dump its ballast weights, the craft may be drifting in the grip of underwater currents – unable to steer or surface.

Analysts say this scenario presents an opportunity – it may be within reach of undersea rescue services otherwise unable to reach the bottom.

But it also presents an extreme challenge: finding the cold, dark, small object in the vast expanse of water. Especially if it doesn’t have an operational emergency beacon.

US officials confirmed on Wednesday that “underwater noises” had been heard, after reports that searchers may have detected banging underwater in 30-minute intervals in the area where the divers disappeared.

US and Canadian aircraft have dropped sonar buoys to listen for any communication attempts.

But the Titan’s underwater acoustic positioning and messaging system remains silent. And, if it carried a beacon, it does not appear to have been activated.

But a complete lack of electrical power has other implications.

Without operational life support systems, the Titan would get very cold. At depths similar to those of the Titanic’s wreck, the average water temperature is just 2C.

And it would be completely dark.

On the bottom

It is possible, but not likely, that the Titan reached its destination – the wreck of the Titanic – before disaster struck.

The mothership reports losing communications just one hour and 45 minutes into the dive. Reaching the bottom usually takes up to two hours, previously published accounts say.

But the craft has reportedly lost contact in the past and returned safely.

The problem with this tourist destination is it is a wreck.

The SS Titanic is a mangled mass of jagged metal. And bits and pieces are scattered around what remains of its intact hull.

Submersibles have a history of becoming tangled in cables and debris.

As recently as 2005, a Russian submersible became trapped at 190m. It took three days for a British rescue submarine to arrive and cut the craft – and its crew of three – free.

Making matters worse is the way this wreckage could mask the Titan’s presence.

“This is a really small object to find,” says Mercogliano.

“There’s two types of sonar they’re using. They’re using passive where they’re listening, in which case, they would want to hear something from the submarine. Active sonar is what you hear in every World War II movie – it pings. But sonar doesn’t typically work down that deep. “And if it does, you’ve got to have a very narrowed focus. And that takes a long time to cover a large area.”

Crush depth

“The worst case scenario is that it has suffered a catastrophic failure to its pressure housing,” says Williams.

“Although the Titan’s composite hull is built to withstand intense deep-sea pressures, any defect in its shape or build could compromise its integrity – in which case there’s a risk of implosion.”

The OceanGate data sheet on the Titan states it has a calculated safety depth of 4000m. That is the level beyond which the 12.7cm-thick carbon fibre tube, titanium hatch and dome and reinforced viewport are not expected to survive.

But there is no margin for error even well above that depth.

An imperfection in the rolled carbon fibre. An imperfect seam between the carbon fibre tube and the titanium end-cap. A weakness in the viewport’s joins.

Any number of weaknesses could produce a sudden failure in structural integrity.

And such a weakness can result from a simple dent – as may occur if a submersible thumps against the side of a ship while being deployed or recovered.

“So OceanGate Expedition’s waiver explains just how experimental this design is. It’s not registered or certified by any agency or the Coast Guard, like some of their other submarines actually are,” argues a 20-year US submarine veteran who operates the Sub Brief YouTube and Twitter accounts.

“This is like an experimental plane, but it’s a submarine. In this case, it spells out the dangers in writing for everybody on board, and that you may die if you ride on board. This submersible says it right there in the waiver.”

But he highlights what he believes to have been a general lack of expertise surrounding the deep-sea tourism project.

And such safety concerns, says Williams, have been a long-term issue for the entire crewed submersible community.

“Currently, most underwater research and offshore industrial work is conducted using unmanned and robotic vehicles,” he writes.

More Coverage

“A loss to one of these vehicles might compromise the work being done, but at least lives aren’t at stake.

“In light of these events, there will likely be intense discussion about the risks associated with using these systems to support deep-sea tourism.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel