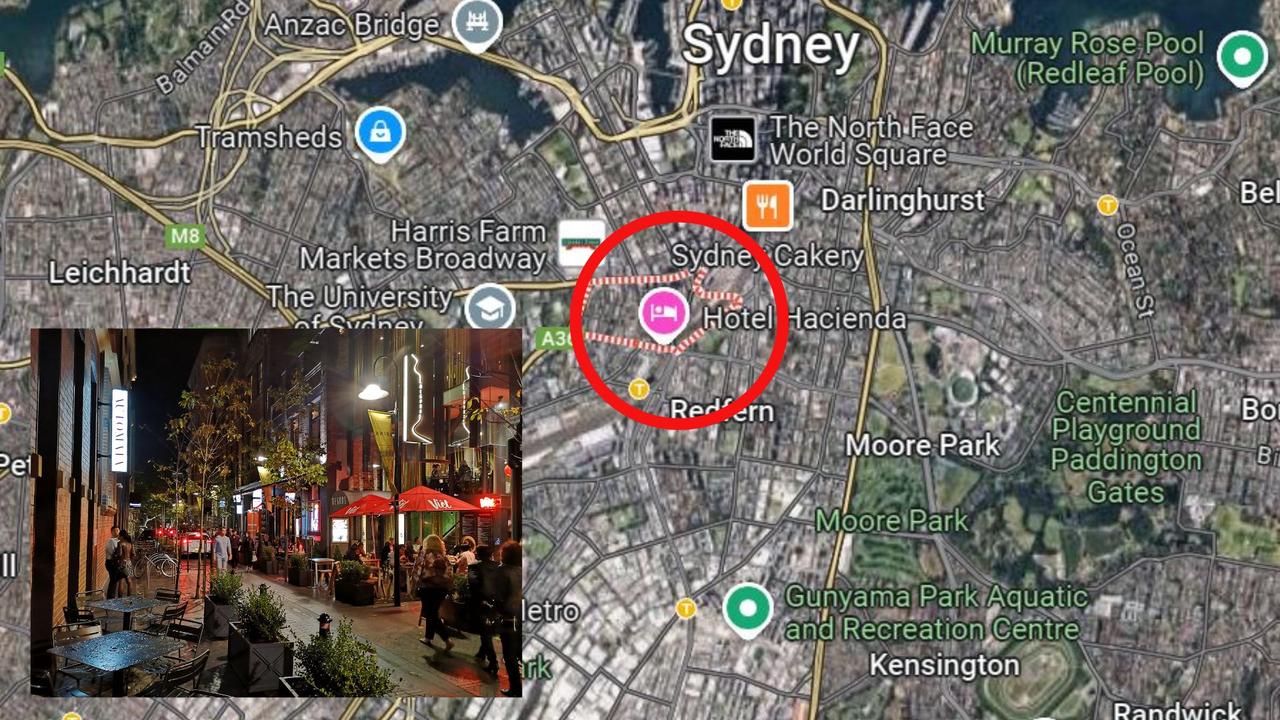

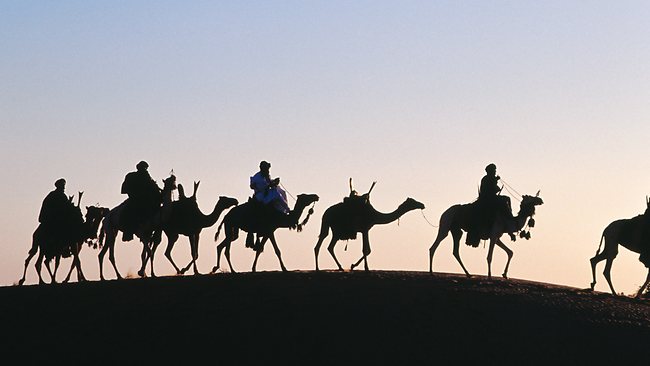

The road to Festival Au Desert, Timbuktu

EVERYONE'S heard of Timbuktu, but have you heard about its music festival? It's a lonely road there, but Lonely Planet says it's worth it.

THE Niger River was too low for the big ferries to run, so I went to Timbuktu in a pirogue - a long wooden motorboat.

Ibrahima, the owner, reckoned it would take us three days, but it could have taken three weeks for all I cared, for I was wallowing in luxury.

It wasn't that the pirogue was so very comfortable, though there was no hardship in its cushions and no sunburn beneath its woven roofing. A couple of braziers in front of the engine served as a kitchen and a screened-off squat-hole at the very back accommodated life's other necessities.

As for the service, Sylla, the boatman, laughed the entire way and Amadou, the cook, attended to our comforts.

But the luxury I savoured most was the prospect of escape from phones and email, meetings and deadlines. I looked forward to 72 isolated hours stretched out watching the world go by as we moved from the bustling port town of Mopti to the never-never-place that is Timbuktu.

Heading out

We were going nowhere and then I was continuing beyond it, to somewhere called Essekane, deep into the Sahara Desert, for a music festival.

We were camped on a rise across the water from the dry-season huts of Bozo fishermen. The kerosene lamp attracted such a variety of crawling and flying creatures that we spent the rest of the evening in moonless darkness.

It may sound peaceful, but it wasn't. The evening started quiet enough, with Amadou singing a gentle delta blues, but before long something that sounded like a disco started up across the river and we could hear the Bozos singing and cheering.

The following night there were other noises. Amadou sang his blues again but this time accompanied by frog croak, cicada rhythm and mosquito whine.

Still, there were no combustion engines, no electric generators confirmation, if such a thing were needed, that we had passed into another world, an old world of foot, muscle and sail.

There we found families of hippos, beady eyes and massive jaws emerging from the water line. Acacia, palm and eucalyptus broke the line of the sand banks; Peul farmers herded cattle on the shore; migrating flocks broke the skyline ahead.

We would be in Timbuktu by nightfall, Sylla announced.

Nowhere I visited expressed the town's character better than the market, where I found traders from upriver Mali, downriver Nigeria, Algeria and Libya, and Touareg, the famous "blue men", who knew better than anyone else how to live in the interior of the Sahara.

As in the 19th century there was also plenty of cloth for sale. Mukhtar, a tall doe-eyed Wodaabe from Niger, asked if I was looking for a chech, a turban. He had one on his head.

"You will need it if you are going to Essekane," he told me, pointing at the sun. He was happy to sell me his own for $5. I offered $4.

"I'll tell you what," he concluded as he transferred the tightly wrapped metres of blue cotton from his head to mine, "how about giving me three?" Even seasoned travellers need time to adjust to the strange ways of Timbuktu.

Music festival

Like almost everyone in the market - and like me - Mukhtar was going to a weekend of music being staged far out in the sands, in Essekane.

So many people were going to the festival that the lonely track had become a piste, and once on it, the journey became a rally that my driver was determined to win.

For three hours he spun the wheel and we veered and jolted as Jeeps and LandCruisers, big desert trucks and vans were lost in our dust trail.

Then, suddenly, the landscape changed, we were in Essekane and I was facing another of those moments requiring adjustment because where I saw drifting white sand, my driver spotted a music festival.

The site looked much as I imagined a trans-Saharan caravan camp must have looked in the days when people had no choice but to travel by camel: a mass of tents of varying shapes and sizes, arranged in some places in rows, in others in clusters.

In the middle of this sea of tents I spotted something you wouldn't have seen in those old camps: two concrete stages and a block of washrooms.

These were the only permanent structures within sight, and around them the wind had carved a natural arena. Everything else had been brought from Timbuktu and beyond. Everyone, that is, except the Touareg.

The word Touareg means "abandoned by the gods", but for a long time these people were also abandoned by man, herding along the borders of the Sahara and trading across the desert for centuries. They were, in other words, the leading citizens of nowhere.

On the long drive back to Timbuktu I had time to chew over this idea, that one person's nowhere was someone else's home. Then something unexpected happened: beyond the darkness, the horizon began to glow orange. What had we found? We made our guesses. A fire? A moonrise? An apocalypse?

We were all wrong. Long before we reached its limits, we were seeing the lights of Timbuktu.

Only now it wasn't the place I had seen before, because everything is relative and because after those days of desert and Touareg, Timbuktu looked bright and unexpectedly bustling, a place of cold drinks and hot food, of hotels, phones and radio, a modern pivot between the Mali of the River Niger and the Touareg-inhabited desert.

It had, in other words, been transformed and was now very much somewhere on the way to nowhere.

This is an edited extract from Tales from Nowhere (2nd Edition), edited by Don George, Lonely Planet. 2011. RRP $24.99.

The Festival Au Desert is held every year in the North of Mali, usually in Essakane, two hours from Timbuktu.

More: Lonelyplanet.com

Offer: Shop online at www.lonely planet.com/escape and get 30 per cent off all of Lonely Planet's travel literature titles. Just enter the code TRAVELTALES at checkout.