Son finds his lost mother in a Stone Age tribe

“SHE’S a naked jungle woman who eats tarantulas!” A man has revealed his mother is actually a member of the Yanomami tribe of Venezuela. This is her life.

WHEN David Good was a kid, and his friends asked where his mother was, he’d always say the same thing: She died in a car crash.

“I experimented with responses, and I found that the most effective,” David told the New York Post. “I could see the horror in their faces” — he laughs — “and there would be no more questions.”

His dad, Ken, couldn’t understand: “I’d say, ‘Why don’t you just say your mum’s Venezuelan, and your parents are divorced? It’s so common.’ ”

Spectacular: Is this the world’s most incredible cave?

But the story of David’s mum — who she was, where she came from and why she left — was so complicated and painful, he couldn’t bring himself to talk about it.

“I didn’t want my friends to know that my mum’s a naked jungle woman eating tarantulas,” he says today. “I didn’t want to be known as a half-breed. And it was my revenge; I was angry that she left me. So I just wanted to stick with the story that she was dead.”

David’s mother, Yarima, is a member of the Yanomami tribe of Venezuela. She was born and raised in the jungle, in a remote village that rarely, if ever, encounters any outsiders, let alone Westerners. Her age is unknown, because the Yanomami count only up to 2; anything more than that is called “many.” They have no electricity, no plumbing, no paved roads, no written language, no markets or currency, no medicine.

They also have no word for “love”.

David’s father, Kenneth, was an anthropology student at the University of Pennsylvania who, under the tutelage of the prominent scholar Napoleon Chagnon, made his first trek to the Amazon in 1975. “I was older than the rest of the team, and a little more arrogant,” he says. Exasperated, Chagnon rid himself of Kenneth, sending him to the most remote part of the jungle.

There, he stumbled upon Yarima’s tribe. He was enthralled and fascinated, and made so many return trips that the Yanomami came to regard Kenneth as one of their own. “The head man of the village said, ‘You know, have a wife — you’ve been here for so long.’ ”

In 1978, he was offered Yarima, who was then about 9 to 12. Good was 36. He saw no real problem.

“Living down there, of course I didn’t care, and the Yanomami didn’t care,” Kenneth says. “Our culture is obsessed with numbers.”

He says that the Yanomami don’t have what we consider marriage; instead, they betroth their girls — even while in the womb — to tribesmen for later consummation.

Kenneth says that a girl can refuse her betrothal, but he knew Yarima had feelings for him, because she watched for him always, brought him food, ran down the riverbank when he was approaching.

Kenneth has always taken umbrage at the obvious question: How old was Yarima when their union was consummated? “PBS asked me that once, and I said, ‘You can be damn sure that she was the age of consent in most states and many countries around the world,’ ” he says. “Which I think is 13. The cultural age is what’s important down there. Don’t I have the right to do this or that in another culture?”

His former mentor Chagnon — himself controversial for his depicting the tribe as bloodthirsty warriors — disagreed and openly criticised Kenneth for “marrying a teenager.” Kenneth’s family, too, disapproved.

“I brought Yarima home to my mother, and she said, ‘Jesus, it’s one thing to study these people — but to marry one? What are you going to do with someone who can only count to 2?’ I said, ‘We’ll work it out.’ ”

Kenneth conducted a long-distance marriage with Yarima, living part-time in the United States on his own, part-time with his young wife in the jungle. He was well-funded by a German institute and had an unlimited expense account, but the Venezuelan government made it difficult for him to come and go at will.

He knew his absences left Yarima vulnerable, but the work was just as important.

Before he departed for a short trip back to the States sometime in 1986, Kenneth told Yarima he’d be back by the full moon, or three weeks’ time. “But I was gone for four months,” he says, and Yarima, her protector gone, was gang-raped by 20 to 30 men over a period of weeks. Her earlobe was nearly shorn off.

“That,” Kenneth says, as if recalling a flat tire, or some other minor nuisance. “She was really angry with me. She said, ‘Why didn’t you come back sooner?’ ” He would later say he made an error in judgment by leaving her for so long, that he knew the Yanomami fear only a female’s husband and that this was a likely consequence.

Kenneth convinced Yarima to come with him to Caracas, so she could receive proper medical care; there, they saved her earlobe. Then he convinced her to come to America.

At the time, Yarima was nine months pregnant with David. They found a doctor to write a note, falsely claiming she was less far along, so that she could fly.

In November 1986, within a week of arriving in Bryn Mawr, Pa., Yarima went into labor and was panicked by the American hospital: the gurneys, the monitors, the machines, the needles. Once admitted, she sprung herself out of bed and attempted to give birth by squatting in the corner of the hospital room.

“It was so unnatural to her,” Kenneth says. “It went against everything she ever learned.”

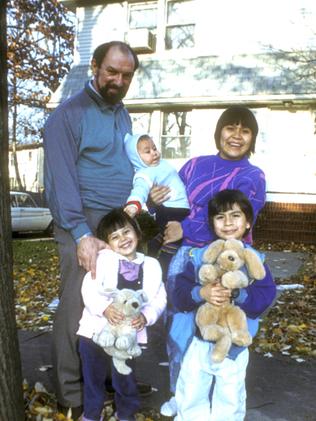

After David was born, Kenneth attempted to settle Yarima into modern American domesticity, with a sprinkling of celebrity treatment: Around that time, a reporter at People magazine caught wind of their story, and in January 1987, Kenneth and Yarima — who spoke no English, no matter — were profiled in a feature called An Amazon Love Story: Romance — and a Jumbo Jet — Took Yarima from the Stone Age to Philadelphia.

Then came the book deal, the movie options, the wooing and flattering. “CBS wanted to do a miniseries,” Kenneth says. “I said, ‘No. I don’t watch television. I want the big screen.’ ”

Alan Alda called and said he wanted to write, direct and star as Kenneth. “I said, ‘Gee, Alan, isn’t that a lot for one man?’ ” Alan Pakula, director of All the President’s Men and Sophie’s Choice wanted in, too.

Kenneth was feeling powerful. “Everybody wanted me,” Kenneth says. “I’m basically at the level of Pacino, De Niro, Redford. Then I get a call from Richard Gere. He says, ‘I just got off the plane from Sri Lanka and I read your People magazine article, and I want to get involved.’ I said, ‘What are you — a producer? A director?’ ’’

But he never heard from Gere again. Alda and Pakula also quit fighting over the rights, and the movie was never made.

Meanwhile, his wife was becoming ever more isolated and desperate. While Kenneth was teaching, Yarima would take the $20 he left every morning and go to Dunkin’ Donuts, then the $10 store, where she never knew how much she could buy. She had to adapt to wearing clothes every day and thought that running cars were animals on the attack. She had no friends.

“I miss my family,” Yarima told People magazine. “I want to go home.” Kenneth was her translator.

‘Anthropologists don’t know humans’

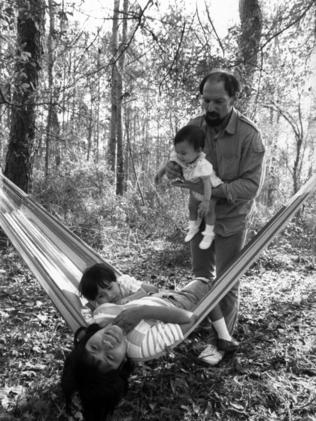

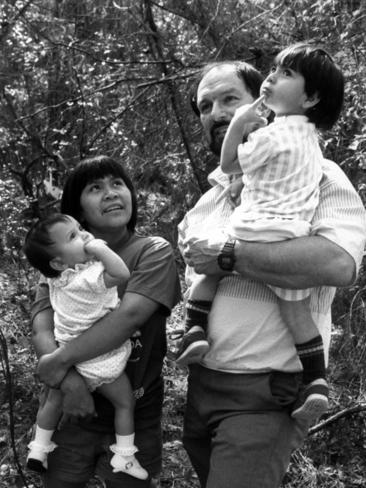

In 1991, Kenneth made a deal with National Geographic: The whole family — which now included daughter Vanessa and baby Daniel — would return to the Amazon for a documentary. While there, Yarima told Kenneth she would not be going back to America.

He says there was no debate over the children.

“She knew the kids wouldn’t do well in the jungle,” Kenneth says. “She told me to take Daniel” — then about 18 months old. “Babies get sick there. They die.”

Both agree, however, that Kenneth never explained to the children anything about their mum — who she was, where she came from, why she left.

David says that for a few years, Kenneth would sit the kids in front of a video camera and have them beg her to come back.

“After two or three years, I began internalising it as abandonment,” David says.

“Sometimes I would bring Yarima up,” Kenneth says. “And when I did — dead silence. I thought, ‘Well, that’s strange.’ ”

Once, when David was about 10 years old, his class took a field trip to the Museum of Natural History. They turned a corner to a small tribal exhibit and there he saw a blown-up photo of his mum, taken by his dad, right there on the wall.

“I just froze,” David says. “All the blood drained out of me. I ran to a dark corner and hid for 10 minutes.”

He never told his dad — who, in turn, had never told David about the day he got a call from the Museum of Natural History, looking to verify that this photo of Yarima was authentic and taken by him.

“We weren’t a touchy-feely, talk-about-things kind of family,” Kenneth says.

David hated his mother but missed her, too, and he resented his father for toting him around to events like some kind of experimental offspring.

“I really hated going with my dad to these conferences,” he says. “I remember the wife of a very prominent anthropologist — I was 12 or 13 at the time — asking me what I wanted for Christmas. I said, ‘A Nintendo 64 with Super Mario Bros.’ She looked at me in horror and said, ‘Oh, my God. You’re a typical American kid. I thought you’d be different.’ That really cut me.”

By 14, David was drinking heavily. He thought that kids who wanted to party would always hang out with other kids who wanted to party — no chance of abandonment there. And the alcohol sanded down the anguish, if only temporarily.

“I used to cry about my mum all the time,” David says. “Usually before I blacked out.

“This would be in public, in private. Then I’d wake up ashamed of myself. These are things my dad doesn’t even know ... Anthropologists study humans, but they don’t know at all how to interact on a human level.”

His dad had a fundamental misreading of David’s identity crisis. “You know what I feel bad about?” Kenneth says. That the Yanomami are short. “David’s only 5’4. I mean, he’s shorter than Al Pacino.”

David found himself wondering what his mum’s side of the story could be. At 20, he began reading the book his dad had written back in 1991. “The parts where I could hear her voice — that was hard.”

At 21, he decided to stop drinking and go visit his mum.

‘I want to be Yanomami’

It took David three years to raise the money for a one-way, $700 ticket to the Amazon. It also took about that long for him to summon the courage to go. His siblings don’t quite understand yet and still want nothing to do with their mother.

“That trip was all about uncertainty,” David says. “I didn’t know if she would like me, or if I would like her, or if she would reject me.”

He arrived in August 2011, the tribe expecting him. When his mother emerged, he recognised her immediately. She wore wooden shoots through her face and little clothing, and he felt immediately that he was her son in every way.

He’d thought a lot about whether to hug her — he wanted to, but he was too nervous, and the Yanomami don’t hug — so he put his hand on her shoulder and told her what he’d wanted to for years.

“I said, ‘Mama, I made it, I’m home. It took so long, but I made it.’ ” Yarima wept.

David stayed with the tribe for two weeks and made a monthlong return trip late last year. He doesn’t travel with anti-snake venom because he can’t afford it, but he also enjoys immersing himself in the culture he rejected for so long.

“My dad tells me not to walk around barefoot in my underwear, but I want to,” David says. When he’s in the jungle, he eats what the tribe eats: grub worms, termites, boa constrictors, monkeys, armadillo.

He has contracted parasites; gotten food poisoning; had mosquitoes attack all of his nether regions, and still he’s happy there.

“I really want to be Yanomami,” David says. “I want to trek through the jungle like they do.”

He says his mother has told him that she wants to come back to America for a visit, to see the rest of her family.

“It’s not like there’s closure,” David says. “We’re at the beginning of our story, in so many ways.”