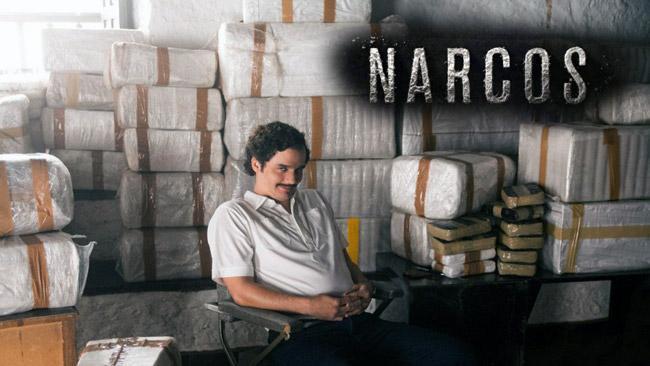

Notorious drug lord back on a high

HE WAS behind thousands of murders, stopping at nothing to protect his trade. It made him one of the world’s richest men.

COLOMBIA’S most notorious drug lord is back on a high, 22 years after he was shot dead by special forces as he fled over a rooftop.

With highly anticipated Netflix show Narcos hitting the screens, and social media littered with snaps of tourists soaking up the legend in his home country, Pablo Escobar is lighting up once more. His story — replete with shadowy plots, assassinations and wild extravagance — has captured the public imagination time and time again, and the “King of Cocaine” has been the subject of numerous movies, books and TV series breathlessly retracing his steps. So why does Escobar keep coming back, and what does that mean for a nation fighting to move forward from a bloodstained past? SMOKING HOT In the Colombian capital of Bogota, you can check out Escobar’s weapons, motorcycle and paraphernalia from his infamous cartel. In his hometown, Medellin, you can go on a two-hour tour that takes in the building bombed by a rival gang trying to murder his family, the house where he was killed and his grave. You can even visit the 7000-acre country retreat, Hacienda Napoles, where this maniacal antihero imported a menagerie of exotic animals from Dallas to live alongside his large concrete dinosaurs. His hippos have since multiplied and gone feral, taking over the surrounding lakes and rivers and causing chaos for farmers. It’s the perfect metaphor for the messy, crazy legend of El Patron. Escobar is everywhere, often portrayed as the archetypal Robin Hood character, after he spent millions building schools, hospitals and churches and giving to poor communities in Medellin. He could afford it. At the height of his power, the kingpin controlled 80 per cent of America’s cocaine trade and was the seventh-richest person in the world, with around $30 billion in the bank. He would stop at nothing to protect his drugs trade, and was behind the murders of thousands of people, offering bounties on police officers and putting hits on journalists and presidential candidates. Escobar ruled Colombia, and it looks like nothing has changed. ‘THE ONLY RISK IS WANTING TO STAY’ The museums, landmarks and tacky ‘I heart Pablo’ t-shirts now provide an important revenue stream for Colombia. For years, they’ve been central drivers of tourism. When I visited seven years ago, there were two reactions. One was to issue dire warnings about the country’s dangerous reputation, and the other was a knowing raised eyebrow over my motivations for being there. That hasn’t really changed. Many tourists visit in the hope of free-flowing coke from the continuing drugs trade, picking up girls in brothels and debauched parties. Others approach with trepidation but leave amazed at the friendliness, unspoilt beauty and elegant colonial architecture of the country. The tourism board has tried to acknowledge and divert its dangerous reputation, adopting the tagline: ���Colombia: The only risk is wanting to stay”. It’s a strategy that is working. The nation is gradually opening up to the world. But many are frustrated that it is still seen primarily as the heart of a trade that ruins lives, with a long-dead villain as its figurehead. CRUEL FATHER Medellin used to be best known for drug violence, car bombs and shootouts between drug gangs, police and militias. Escobar’s illicit activities turned Colombia’s second-largest city in murder capital of the world, with Al Jazeera reporting 6349 murders in 1991, the year leading up to his arrest. Now it’s a popular tourist hub with a thriving population of young professionals and relatively safe, since the murder rate fell by 80 per cent. But poverty and destitution persist on the city’s outskirts. Escobar’s dark history has given Colombia an opportunity, and a tale it won’t be able to forget. “Everything runs through him, like a spinal column,” Andres Parra, star of soap opera El Patron del Mal (The Boss of Evil), told GQ in a recent profile of the drugs lord. “Politics, sports, fame, fortune, the modern history of our country.” Many ordinary Colombians still worship Escobar, displaying statuettes and pictures of the drug lord in the same way some British families keep framed photos of Princess Diana. Thousands went to his funeral and many more make pilgrimages to his grave. A bustling neighbourhood he built for the paupers of Medellin remains known as Barrio Pablo Escobar, despite the authorities’ efforts to deny its existence. His family have embraced it, with his co-conspirator brother chatting to tourists on Escobar tours, and his sister writing a book about him. His son Juan was 16 when his father was gunned down, screaming on live radio that he would “kill the f***ing bastards” who had murdered his father. Instead, he was forced to flee the country, change his name and slowly come to terms with the weight of inherited wrongdoing. He, too, has written a memoir, revealing the challenge of having the country’s cruel father as his own. COMPLICATED STORY Escobar’s epic criminality can’t be overlooked. In 1989, the year he appeared on the Forbes rich list, he orchestrated the bombing of Avianca Flight 203, killing 107 people. He is thought to have been responsible for around 4000 murders in all, and relatives of his victims have compared his son starting a clothing line to “commercialising Hitler”. The outlaw showed little regret for killing and hurting so many, and making drugs and death synonymous with his country. When he was arrested in 1991, he forced authorities to let him build his own jail, ‘The Cathedral’, where he continued to enjoy a lavish lifestyle and preside over his cartel until the police came for him and he went on the run. Eric Newman, co-creator of the new Neflix series, insisted in a Guardian interview he’d avoided the “slightly heroic drug dealer thing”, but it’s a plotline that’s hard to shake off. Escobar may have done more harm than good, but this one long-dead man has been saddled with a large portion of the blame and praise for his country’s national identity. Colombia is becoming a destination. Escobar may have put it on the map for drugs, violence and sex, but it’s now going mainstream. Middle-class tourists are embracing it, Starbucks arrived last year and Mark Zuckerberg even visited to help improve internet access. When Escobar died on a roof in December 1993, his family had to prove it by exhuming his body and running DNA tests, after rumours abounded that he was alive, with a new identity. He may be gone, but his legend will shape his country for a long time to come.