‘I could have been a narco’: Aussie’s ‘white nights’ in Colombia

EXPLORING Colombia, this Aussie had no idea he would find himself surrounded by drug kingpins who wanted him either dead or on their team.

AUSTIN Galt was just an ordinary kid from Sydney. Now he was face-to-face with a notorious gangster in a dodgy little casino in Cali, a Colombian city known for a brutal cartel nicknamed Cocaine Inc.

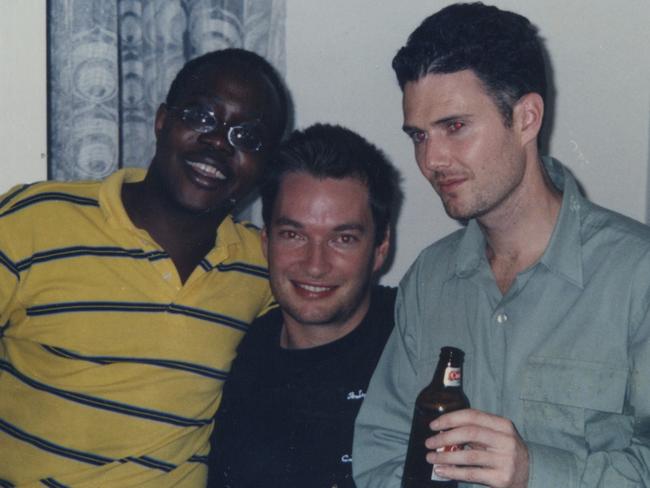

This was 2001, long before hit Netflix show Narcos popularised the story, and Austin was one of few tourists, let alone Australians, travelling South America in search of adventure.

The young backpacker had befriended a local named Pedro, but as the pair faced down an irate drug kingpin, he wondered whether he had gone too far in his quest for excitement.

“There was a bit of tension arising at the table playing blackjack together,” Austin told news.com.au. “Things were clearly getting out of hand. And basically we were surrounded by his sicarios [hired killers for South American drug cartels].

“We were completely surrounded by hitmen ... obviously the word had got around to the sicarios, and they just swarmed our table and sat everywhere, right on my back, several of them right on my back. Who knows what could have happened? It was a dicey place.”

Cali was one of the more dangerous cities at the time. It still is, according to Austin, but when he was first there, “it was kind of like the Wild West.”

A model and banker back in Australia, the wide-eyed 26-year-old could only be grateful for the protection of Pedro — although they were terrifyingly outnumbered.

“If I wasn’t with Pedro, I’m not sure how things could have turned out,” he said. “I’m not sure how they would have turned out, I don’t want to know.”

But by this point, Austin was growing addicted to the risky atmosphere in this renegade nation, particularly in cities like Cali. “You could just sense it, feel the tension in the air, sense it in the air — the edginess, the sense of danger,” he said.

‘PEOPLE FIRING GUNS, MAFIA HITS, DEAD BODIES ALL OVER’

The southern city is the setting for the third series of Narcos, which follows the escapades of Cocaine Inc, aka the Gentlemen of Cali, who carried out their business like a particularly bloodthirsty corporation. Their approach was totally different to that of “King of Cocaine” Pablo Escobar, whose glittering reign was brought to an abrupt halt when he was shot and killed by police in his hometown of Medellin.

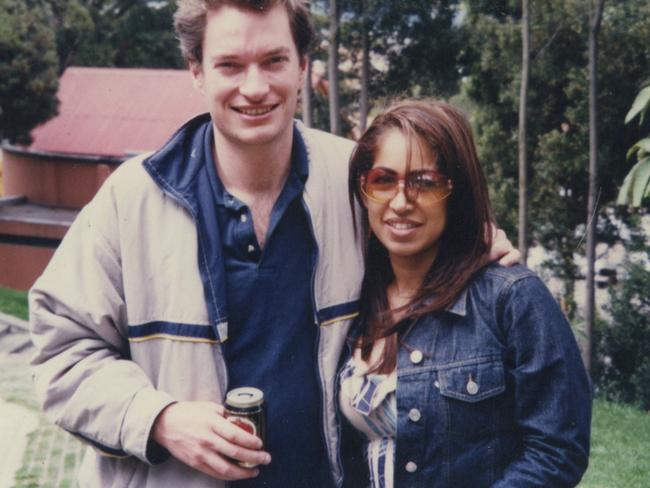

Austin now lives in Medellin himself, along with Colombian wife Lily and their two young daughters. Now 43, he’s not interested in trouble, but appreciates the country for its spectacular natural beauty as well as its fascinating story, which he has interwoven with his own in his first book, White Nights.

“The news back in the day, you didn’t need to go to the movies,” he said. “It was like action central on television. The war in the countryside between the guerillas and the army, it was like, you see people firing their guns, you see mafia hits, dead bodies all over the place, on highways on street corners, it was just all action.

“And all different cartels, all different players throughout Colombia. And I’d go, wow, there’s a whole other story apart from the Cali and Medellin cartels that the outside world just has no idea about.”

When he’s not writing, Austin devotes his time to his family and technical analysis of the stock markets, but he once came perilously close to entering deeper into the world of cocaine trafficking.

It was his friend Pedro who offered him the opportunity to dive into the lucrative and exciting world of the drug mafia. It was a moment when the young Aussie’s life could have gone either way.

“I could have just said, ‘OK let’s go, let’s do it,’” he said. “It would have been as easy as that. But you know when that moment, when the question hit me, it was, it was kind of like a, whoa, this is serious, if I do say, ‘OK let’s do it’, then I’m going down a whole other path, potentially a very dark path.

“When you’re not hit with that question with someone like Pedro, you think, oh, perhaps, you know, you’ve seen movies, yeah, that looks great, but when you’re actually hit with the question, you perhaps think differently about it.

“After being asked by Pedro I knew, it was then the realisation that, no, I didn’t actually want to be involved. I pretty much entered that world as far as anyone could without actually becoming involved, and that’s how I liked to leave it.”

But Austin’s brushes with danger continued. From the moment he entered the country and was hauled off a bus to be searched by guerillas carrying AK-47s, to when a drug trafficker threatened his life after a disagreement, fear was often just around the corner.

That’s not something he believes is a bad thing, and while the safety of his family is paramount, he wants his daughters to experience Colombian culture, and to see its less than perfect side.

“Whether it’s the danger, the increased poverty, or you know, it’s a hard life for many people, so at least experiencing that and then say if they do come back to Australia, they will not take life for granted as, say, I might’ve when I was a boy, growing up in this safe society, not seeing other parts of the world ... not knowing how other people live,” he said.

‘THE WILD WEST STILL EXISTS’

Since the guerillas have been eliminated and as regulation develops, Austin says Colombia is a far easier place to travel, and is becoming increasingly popular. But it hasn’t completely changed.

“The cities are becoming safer, there’s sort of safety in numbers with all the tourists there. But outside the cities certainly the Wild West still exists,” he said. “I feel comfortable there now, I’ve been around the people so long. There’s comfort factor there for me. If you’ve just arrived in the country, you may feel scared just being in the cities, let alone going out to the Wild West countryside, so but it’s — you know the place, like anything, you become more comfortable with time.”

During his travels, he created his own personal code for getting by, which has stood him in good stead. “Whatever you do, just don’t mess with anyone, because you don’t know who you’re messing with.

“That’s generally what I’ve tried to live by there ... just being friendly, don’t be rude, you don’t know who you’re being rude to.”

But while the paramilitaries have gone, “a lot of them it’s just converting to straight up criminals, drug traffickers, without the pretence of being a right-wing paramilitary or a left-wing guerrilla,” said Austin.

“The amount of cocaine is as high as it’s ever been, that hasn’t stopped, it continues unabated, it’s just in pure criminal’s hands instead of being under the control of guerillas and paramilitaries.”

He believes Colombia will only truly solve its problems if drugs are legalised, since “taking out the criminal element you’ll decrease crime, a lot of violent crime.”

What’s more, he says taxpayers the world over would be shocked at how many billions of dollars governments spend on the war on drugs. “Fifty per cent of the prison population is there for drug-related crime,” he said. “They lock up one criminal, a new one emerges. There’s a never-ending supply of people willing to take over.

“I don’t want my daughters doing cocaine but you know, on a practical level, it’ll be easier for my girls to get marijuana and cocaine than to buy liquor in the store because the owners don’t want to lose their licence.”

Austin notes that many people are now moving on to drugs like heroin and ice, which are far more dangerous and addictive. The rich set in Colombia are taking “pink cocaine”, a synthetic methamphetamine that is extremely expensive, and therefore considered more desirable by actors and lawyers in a country where cocaine is everywhere, and in contrast to Australia, considered a low-class drug.

“The thing in Colombia is everyone knows someone who’s involved with the drug trafficking business,” said Austin. “It’s a narco culture.

“It’s becoming frowned upon as time goes on, but back in the 70s, you’ve got the top families of big cities, you know, generally being involved in the trade.

“Generally, everyone pretty much knows or has a family member, whether an extended family member, somehow involved in the trade.

“Whether it’s a bodyguard, someone who launders money, they know someone or have a family member involved, it’s right throughout the culture.”

emma.reynolds@news.com.au | @emmareyn

White Nights is available now for $34.99 from Pan Macmillan Australia.