Other people of this remote Canadian island village are taking government money to clear out, but one couple is staying

Having always dreamt of moving to the Little Bay of Islands, this couple never expected to be the regions last inhabitants.

Mike Parsons always dreamt of retiring to his hometown of Little Bay Islands.

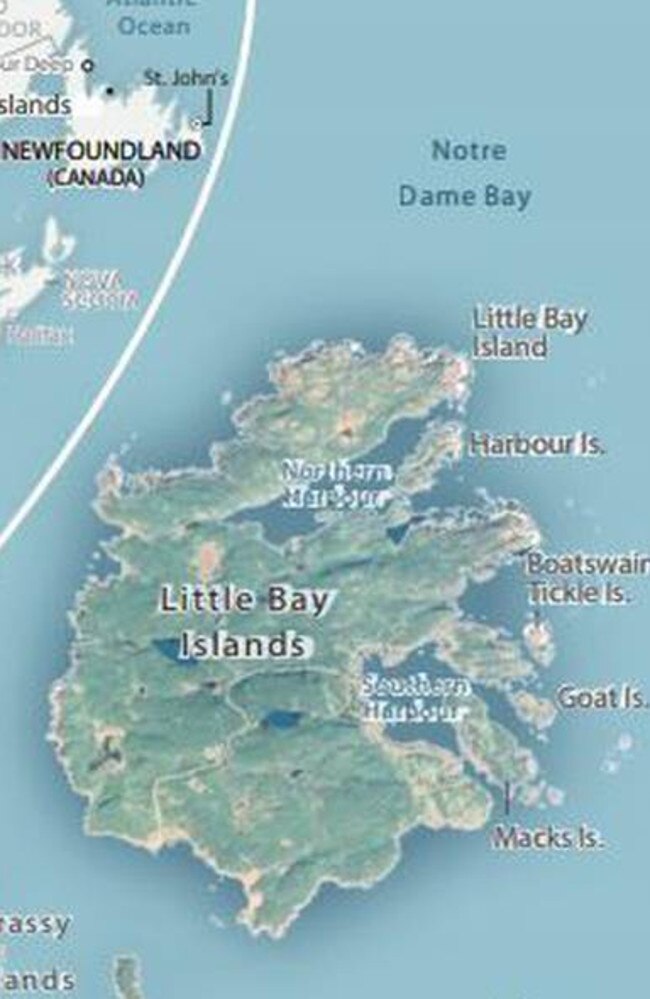

But when he and his wife moved back to the four-square-mile outpost off Newfoundland’s northeastern coast in 2017, he never imagined they’d be its last inhabitants.

Mr Parsons, 53, remembers Little Bay Islands as a thriving village of hundreds at the centre of the province’s booming cod fishing industry, a postcard of bucolic bliss with its green forested hills, brightly painted saltbox homes, bustling shops and lively dockyards huddled around a small blue harbour.

Now, it’s down to some 54 souls, most of them in their twilight years. A moratorium on commercial cod fishing in 1992 prompted many to look elsewhere for work. The fishing plant shuttered in 2010.

The school sits empty. For years, the only items for sale in the village have been the stamps at the post office.

Newfoundland and Labrador takes a different approach: It pays you to leave.

Faced with mounting debt and still struggling to recover from a fishery collapse and an oil-price slump, the government pays households in declining, expensive-to-serve communities $282,000 to $305,000 to move – and then cuts off services to the community.

There are a few conditions: The request must come from the community, not the province; at least 90 per cent of residents must vote to leave; and a cost-benefit analysis must show a likelihood of net savings.

The people of Little Bay Islands voted unanimously this year to abandon the island – the eighth such community to make the decision in the last two decades. Derrick Bragg, the provincial minister of municipal affairs and the environment, said resettlement will cost US$6.61 million, but will save the province roughly US$22 million over two decades. He gave the green light in April.

On Dec. 31, the government will cut off all services to the community, including electricity, snow removal and ferry service. Residents may keep their homes, but will have to use them off-grid. Volunteers have rescued the islands’ feral cats, after the provincial government said it might euthanise them.

A “palpable sadness” has settled over the town as islanders load their belongings into U-Haul trucks, Parsons said. He ticks off a series of “lasts” in recent weeks: the last church service, the last mail delivery, the last night at the “Poachers Lounge,” an unofficial hangout where villagers played darts and sang songs.

“It’s absolutely heartbreaking to see these people trying to pack up a lifetime of stuff and move elsewhere,” Parsons said. “Most of these people have only ever lived on Little Bay Islands.”

Resettlement has a long and controversial history in Newfoundland and Labrador. When the former British dominion joined Canada in 1949, Premier Joey Smallwood struggled to provide services to the 1,200 outposts that dotted the coast.

In 1954, he started the first of several centralisation programs that gave cash to households from villages with “no great future” to move to government-selected “growth centres.” From 1954 to 1975, roughly 28,000 people from nearly 300 remote outposts were uprooted and resettled, many of them dragging or floating their houses to their new communities.

The programs were controversial from the beginning. Often, the growth centres were themselves isolated, lacking in opportunities and unprepared for the new arrivals. Rumours swirled of a “black list” of places the government would shut down. People said they felt forced into moving.

Jeffrey Webb, a professor of history at Memorial University in Newfoundland, said people “weren’t explicitly threatened,” but there was “gossip and rumour and fear” that if they didn’t take the money, services would be cut anyway, and they’d still be forced to move, without compensation.

In a letter to a concerned resident in 1958, Smallwood said he didn’t “intend to spend public money to help people jump from the frying pan into the fire.” But to this day, resettlement is highly charged, and the programs have been memorialised by writers, artists and in protest songs.

In 2002, Great Harbour Deep became the first community in a generation to resettle. Six others followed suit. Little Bay Islands is the next. Bragg said the province is considering a request from one other community.

Little Bay Islands considered resettlement for nearly a decade in a process that pit neighbour against neighbour, generation against generation – and illustrated how informal coercion can be necessary for the program to work.

In 2015, 95 voters cast ballots in a referendum on resettling. They needed 86 votes. They got 85. In a small community, word of who voted “no” spread quickly.

“That created a lot of bad feelings,” Parsons said. “People stopped talking to each other. Those who voted against leaving were kind of shunned by the community, and now they sort of just succumbed to the pressure.”

A rift between permanent residents and seasonal residents emerged.

Under the program, only a person who “lives and sleeps year-round” in a community is eligible to vote on relocation. Seasonal residents, who outnumber permanent residents in Little Bay Islands, are not. (The locals call seasonal residents “stouts,” after a bloodsucking deer fly that’s hard to shoo away.)

Carolyn Strong spent the first 16 years of her life on Little Bay Islands. As a little girl, she would eat dinner with the European ship captains who sailed their trading vessels to the island in search of salted fish. As an adult, she learned the sand she had played in as a child had been brought as ballast for ships from as far away as Europe and Africa.

Strong, 81, moved from Little Bay Islands to start a nursing career. But she has two homes on the island and returns each summer, but is among those who were not allowed to vote.

“Money drove this vote,” Strong said. “The summer people had no acknowledgment from the government at all.”

During the days of Smallwood’s programs, she said, she would “pray that nobody would touch Little Bay Islands.” Today, she questions whether such programs should even exist.

Several seasonal residents who were not allowed to vote are considering legal challenges.

Bragg acknowledged the process can be “a little contentious.” It’s impossible, he said, “to please 100 per cent of the people.”

Does he think Newfoundland’s resettlement program is a success? “I guess you would have to ask the people who move,” he said. “I’m just the person who is writing the cheques.”

Bob Pittman was the last resident to leave Great Harbour Deep. He and most of his former neighbours have done well since resettlement, he said. But he likened the feeling of leaving to “almost like having a death in the family.”

“I didn’t want resettlement myself,” he said. “But I voted (to leave) because it would create so many problems if you tried to stop it.

“I still miss my home.”

Parsons was also denied a vote – he hadn’t lived on the island for a full year when the village requested relocation in 2017. But he and his wife, Georgina, 44, have decided to stay behind. They’ve spent more than US$38,000 on solar panels, generators and other items so they can live off-grid. They’ve stockpiled goods and completed first-aid training. They expect some neighbours to return in the summer.

On Dec. 31, the power will be cut, leaving Little Bay Islands in the dark. Then Mike and Georgina will throw the lines for the MV Hazel McIsaac ferry as it makes its final trip.

Parsons’s mother worries, he said. But other islanders have told them they’re relieved someone is staying behind.

“It gives them a sense of peace that the island won’t be completely dead,” he said. “There’s someone who is going to be carrying the torch forward.”

This article originally appeared on the New Zealand Herald and has been republished with permission