River Thames now teeming with marine life, decades after it was declared ‘biologically dead’

London’s River Thames has been “biologically dead” for decades - but a massive effort to clean up the filthy waterway has had an interesting impact.

Sharks are now living in London’s River Thames — with the waterway teeming with life 64 years after it was declared “biologically dead”.

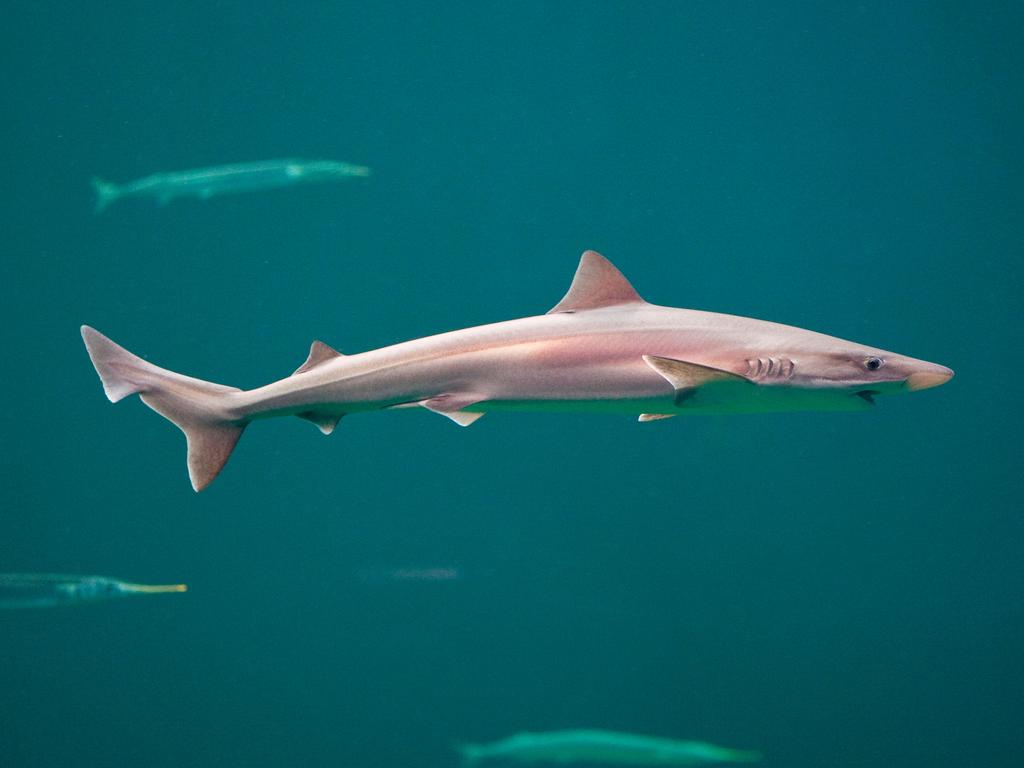

Shark species including tope, starry smooth-hounds and spurdogs, which release venom from fins, are using the cleaned-up waters as nurseries, The Sun reported.

The sharks like giving birth in shallow bays and estuaries, with young sharks remaining in the river for up to two years.

Seahorses, oysters, seals and critically endangered eels have also been found in the river’s first full health check since 1957.

The Zoological Society of London’s Alison Debney said the Thames now supports more than 115 species of fish, 92 species of bird and has almost 600 hectares of saltmarsh — a crucial wildlife habitat.

“Estuaries provide us with clean water, protection from flooding and are an important nursery for wildlife,” she said.

“This report has enabled us to really look at how far the Thames has come on its journey to recovery.”

Aggressive tope sharks, which have distinctive long snouts, grow up to 1.8m (6ft).

The smaller starry smooth-hounds are able to crush crustaceans with their powerful jaws.

Spurdogs often swim in shoals and their venom can cause “extreme discomfort” in humans.

Their emergence in the Thames is proof of how successful conservation work has been in improving water quality and oxygen concentrations.

But rising temperatures and water levels are posing an ever-greater threat to ecosystems.

The level at Silvertown, in East London, has been rising 4.26mm a year since 1990.

Meanwhile, the Environment Agency has identified industrial and sewage waste as a further threat.

This could be alleviated by the £4 billion ($A7.32 billion) Thames Tideway Tunnel — known as London’s new super sewer — due to be completed in 2025.

It should capture more than 95 per cent of the sewage spills that enter the river from London’s Victorian sewer system.

This article originally appeared on The Sun and has been republished here with permission.