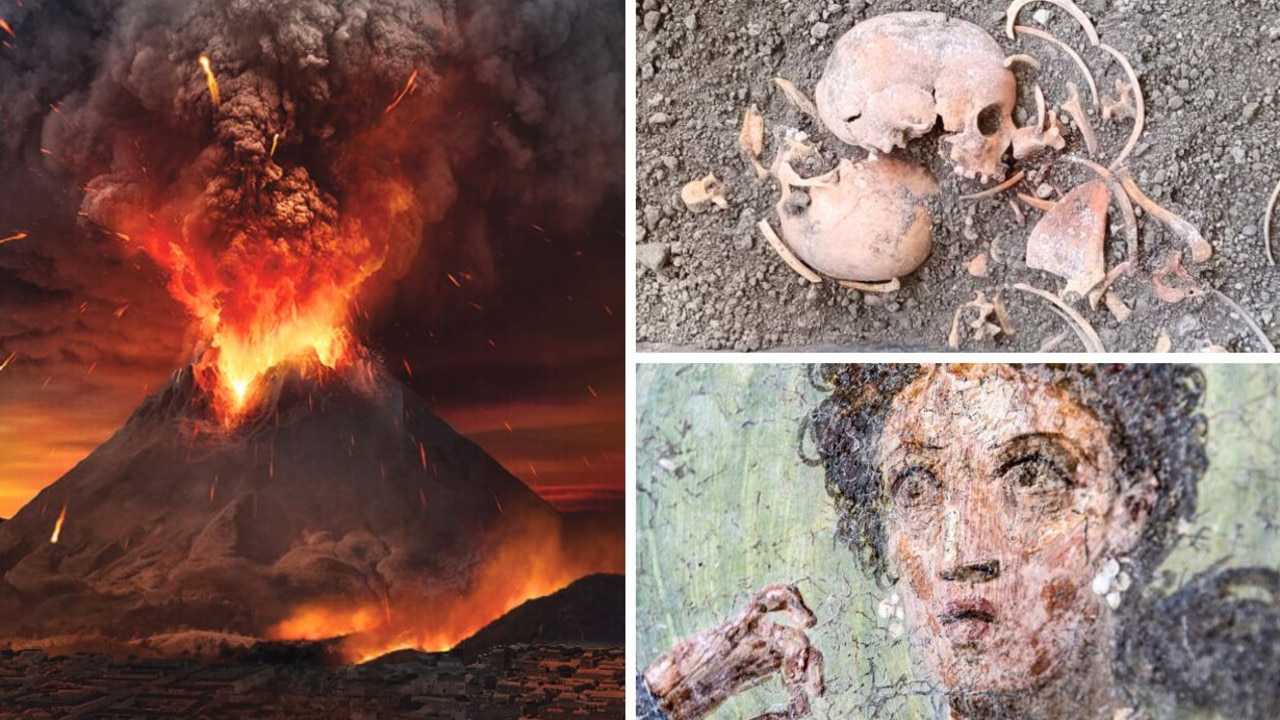

Incredible new Pompeii find sheds light on secretive ‘sex cult’

A wild new discovery inside the ruins of Pompeii has answered questions historians have asked for over 2,000 years.

Sex. Drugs. And the Roman version of Rock’n’ Roll.

Pompeii knew how to party. But you had to be an initiate first.

And a new discovery embraces the wild side of the ancient empire’s women.

Yet another richly decorated banquet hall has been dug out of the volcanic dust and rubble. What makes this one special is the life-size frieze that runs along three sides of the room.

It shows a Thiasus (procession) for the god of wine and festivity.

And it celebrates the admission of a young woman to the mystery cult.

“For the ancients, the bacchante or maenad expressed the wild, untameable side of women,” says director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii Gabriel Zuchtriegel.

“(It’s about) the woman who abandons her children, the house and the city, who breaks free from male order to dance freely, go hunting and eat raw meat in the mountains and the woods.”

The fresco provides insight into the secretive cult of Bacchus – the god of frenzy and ecstasy.

The damaged central scene shows an older man whispering to the initiate. He’s holding a torch to light the way. And above the panel is a strange scene of snakes and fish.

Female celebrants shown as dancers in diaphanous gowns or naked hunters carrying their catch are arrayed on either side. Prancing among them are the cult’s iconic human-goat hybrid satyrs playing flutes and drinking.

“These frescoes have a profoundly religious meaning which, however, was also designed to decorate areas for holding banquets and feasts,” Zuchtriegel explains, “rather like when we find a copy of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam on the wall of an Italian restaurant in New York to create a little bit of atmosphere.”

Women unchained

“What we see is actually a scene of initiation into the mysteries of Dionysus (the Greek name of Bacchus). In antiquity, various mystery cults existed, not only with regard to Dionysus, but also of Demeter and Isis,” says Zuchtriegel.

All involved secret initiation rites, closely guarded beliefs, and intense ceremonies designed to create a spiritual experience for participants. While not official pantheon religions sponsored by the Roman state, they were widely tolerated as somewhat scandalous pursuits.

The symbology of the newly uncovered banquet hall frieze appears simple. It’s colourful. It’s energetic. It’s filled with an abundance of food and wine.

“The hunt of the Dionysiac bacchantes was “a metaphor for an unrestrained, ecstatic life that aims to achieve’ great, wondrous things’,” Zuchtriegel explains.

But the cult was built around the myth that Bacchus had been “born again”.

Some accounts say the son of Persephone had been torn apart by the Titans, the predecessors to the gods. But the king of the gods and his father, Zeus, had his heart recovered and used to bring him back to life through a second mother, Semele.

Another says he was born twice. The unborn godchild survived the killing of his mother, Semele. Zeus then carried him to full term by sewing him into his thigh.

Most of his myths tell of the boy-god growing up, discovering wine, and rejecting the strictures of civilisation for the pursuit of pleasure and a simple life.

The newly discovered fresco shows his tutor and mentor – the old man Silenus – introducing a woman to the cult, promising “rebirth” into a new life of bliss and plenty. But while Bacchus was worshipped for bringing joy wherever he went, he could drive wayward followers into madness.

Archaeologists say the freshly excavated house, dubbed Thiasus after the Bacchanalian procession, had been painted some 40 years before the eruption.

It’s not the only Pompeii mansion to celebrate the god of excess. The “House of Bacchus” was excavated in 1879. One of its frescoes shows the god standing beside Mount Vesuvius, wrapped in a gown of giant wine grapes. Beneath writhes another sinister snake.

Ancient interior design

Roman builders had a clear philosophy: axiality – the Durchblick or “view through”.

Researchers say this wasn’t just an architectural idea. The “right to a clear view” was also a part of Roman law.

A virtual reality reconstruction of a Pompeian villa demonstrates how this played out in its occupant’s daily lives.

The study in the American Journal of Archaeology tracks the sight lines of visitors as they enter and move through one excavated villa, the House of the Greek Epigrams.

It shows Roman builders and interior decorators used layouts of long, straight, clear lines to allow people to see through most of the house. But what they saw, and when, was tightly scripted.

“Archaeological investigations conducted on the physical remains of Roman houses and their decor have emphasised the highly ritualistic character of the domestic space, in that it encompassed activities (both religious and habitual …) that were formalised and meaningful,” the study reads.

In the case of the House of the Greek Epigrams, those on the street passing by see “suitably modest motifs, deliberately concealing more luxurious decorative elements”.

But guests were given the full sensory-manipulation experience.

The artworks exploit the shifting focus of the eye to bring frescoes to life. And different scenes move in and out of the shadows at different times of the day to evoke tailored moods.

As with modern interior design, it was as much about the “construction of the identity of the owner of the house” as it was decorative.

“Rather than rooms with a single view or multiple views, the Roman house would have offered a complex visual palimpsest made up of moving views, interconnected journeys, and comings and goings, of successive investigations in search of the unexpected new detail and mnemonic connections, through the skilful visual play of paintings under the light and in the shadows,” it concludes.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social