Should Aung San Suu Kyi give back her Nobel prize?

CALLS are growing for Myanmar’s unofficial leader to hand back the award in the wake of her country’s atrocities.

IT’S HARD to imagine a place that would condone soldiers savagely beating a mother in labour, then stamping her newborn baby to death.

Tragically, it’s not something from a horror movie.

It’s an atrocity allegedly committed against a Rohingya Muslim woman by her own government in Myanmar, the Asian country formerly known as Burma.

Ironically, the nation’s unofficial leader has a Nobel Peace Prize, although a petition is widely circulating online demanding her to give it back.

For centuries, Rohingya people have lived in Rakhine state, an incredibly poor region tucked away in the country’s south west on the border with Bangladesh.

They’ve been described as the world’s most persecuted minority.

According to a United Nations Human Rights report on the crisis this year, they are not only denied citizenship, but subject to all kinds of horrors.

Women and girls have been violently raped, and some died from their injuries.

Children have had their throats slit in front of their families.

Helicopters have randomly sprayed villages with gunfire.

People have been locked into their homes and burnt alive.

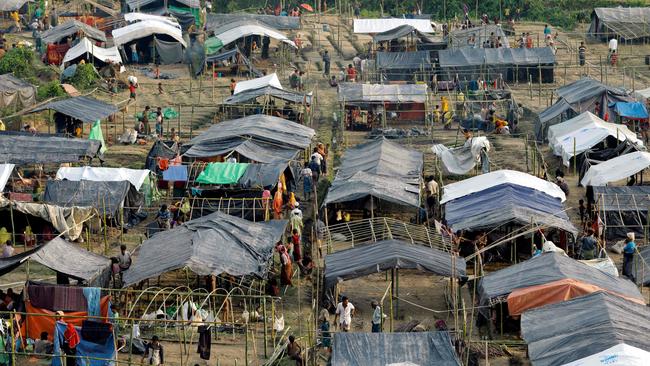

The situation is so bad some 120,000 people have abandoned their homes and fled across the border into Bangladesh in the last two weeks.

They blame the government, and say they are being subject to genocide.

The government, however, says they’re terrorists and it has the right to defend itself.

Aung San Suu Kyi represented great hope for a troubled nation.

Daw Suu, as she’s known, was educated at the University of Oxford but returned to Burma in the late 1980s to fight for democracy.

She founded a political party called the National League for democracy in 1988, but she was placed under house arrest in 1989 before the general election.

Her party won in a landslide, but the military refused to recognise the result.

She spent 16 of the next 21 years imprisoned in her own home, turning down repeated offers of freedom on the condition she left the country and never returned.

She suffered greatly during this time, forcibly separated from her sons and her dying husband, but she remained a beacon of hope.

Daw Suu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her “non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights”, which selectors considered “one of the most extraordinary examples of civil courage in Asia in recent decades”.

Two decades passed before she could officially accept her award and deliver the traditional Nobel Lecture, where she famously said: “Wherever suffering is ignored, there will be the seeds of conflict, for suffering degrades and embitters and enrages”.

When it comes to Rohingya people, however, her silence has been deafening.

In 2012, Rakhine state exploded in violence, with a series of bloody conflicts between Rohingya Muslims and local Buddhist groups.

Homes were burned, women were raped, and people were killed on both sides.

Eventually a state of emergency was declared, and the military dispersed the combatants, but Daw Suu was notably silent.

In 2015, her party won again, paving the way for the first non-military president in 54 years — however, a sneaky constitutional change barred her from taking office on the grounds she is the mother of foreign children.

The same year, violence forced thousands of Rohingya to flee Myanmar, climbing into rickety boats and attempting to sail to Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Many died at sea, and still she refused to speak.

In August this year, government forces allegedly committed mass killings as part of what it called “clearance operations”, burning down some 2600 villages.

This week, 2014 Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai begged her fellow laureate to condemn “this tragic and shameful treatment”.

Still, Daw Suu has said nothing.

Myanmar is poor but incredibly beautiful, and it recently opened its borders.

Visitor numbers have exploded from 300,000 in 2010 to 4.7 million in 2015 as curious foreigners rush to beat the masses.

News.com.au journalist Gavin Fernando recently spent four weeks exploring the country, and he described it as an “untouched haven”.

“Myanmar’s appeal instead lies in small, simple pleasures — a solo bike ride weaving through isolated temples, a hike through the untouched mountains, a sunset boat ride in the vast lake,” he wrote.

Aung San Suu Kyi will never be President of Myanmar, and she will never control the army or have the ability to stop the violence directly.

However, her voice will always be incredibly powerful.

In 1996, she urged tourists to stay away so their money didn’t go to the military.

“Visiting now is tantamount to condoning the regime,” she said.

“Burma will be here for many years, so tell your friends to visit us later”.

Clearly, it’s still too soon.