Tragic love story behind city’s name

The tragic tale of immense love, sacrifice and scandal is behind how one of the cities along Egypt’s Nile River got its name.

In the last week of October, 130AD, a man died and a god was born.

Under the slanting sunlight of late summer, a body was found in the floodwaters of the River Nile, near the little town of Hir-wer.

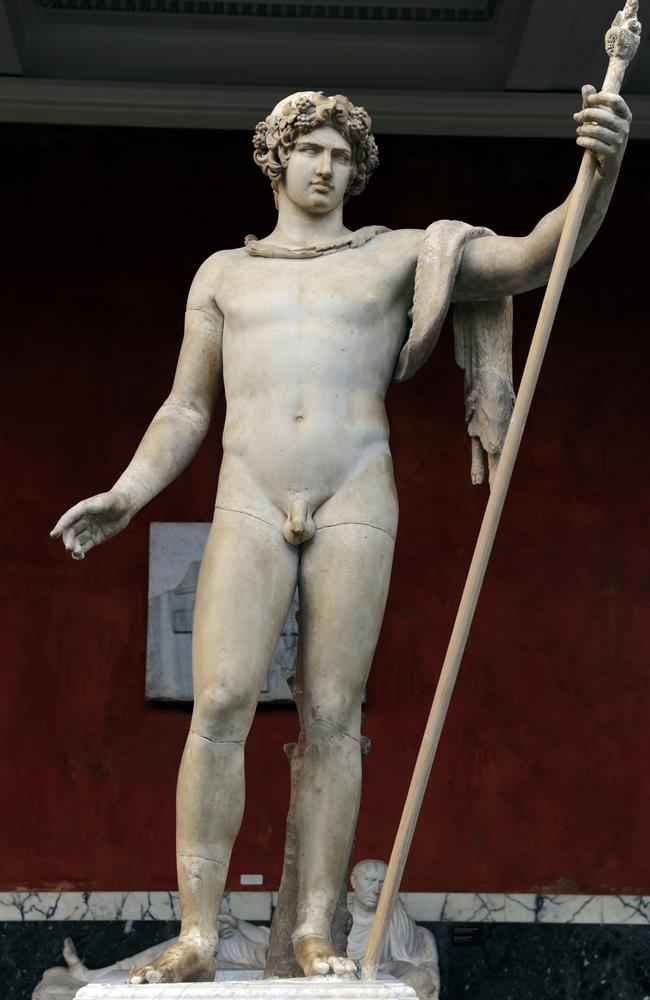

It was that of a young man — aged 18 to 20, athletic in build and with hair clustered down his neck in thick curls.

There were no signs of violence on his body.

Thus, rumours started circulating around the circumstances that led to the fatal event.

RELATED: Grim truth of Russia’s ‘City of the Dead’

RELATED: Incredible palace that was hidden from the world

RELATED: ‘Disloyal’ royal consort vanishes

Murder? Suicide? Accident? Sacrifice? Conspiracy?

There was endless speculation, but not a clue as to why such a vigorous and healthy-looking young man had met such a premature death — apart from the evident fact that he had drowned.

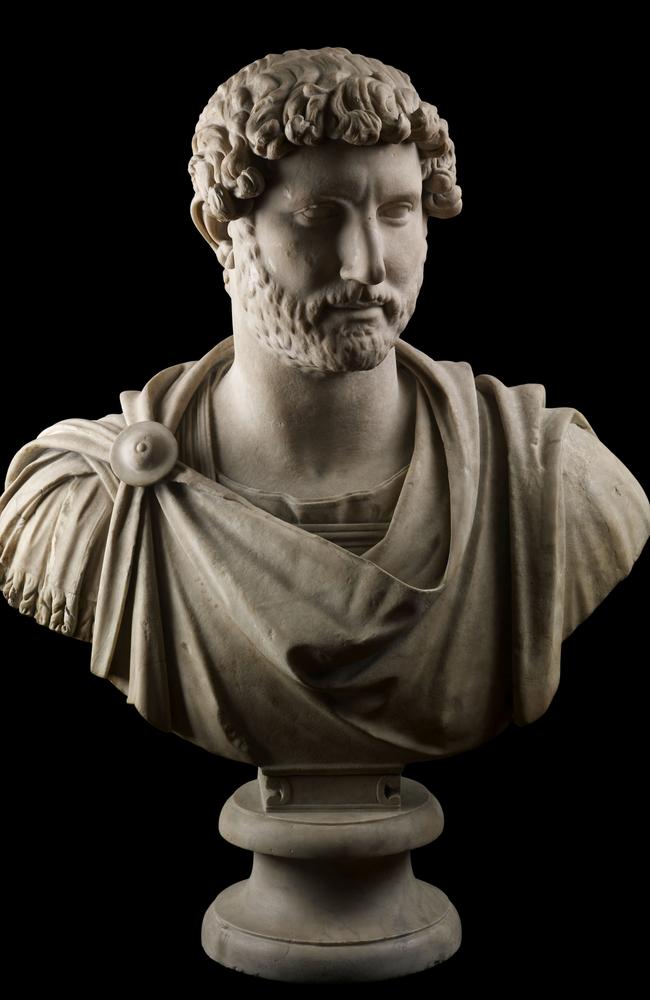

His name was Antinous. And he was the Greek boy from Bithynia (now Turkey) — the great love of the 54-year-old Roman Emperor himself, Hadrian — who, at the time, was the most powerful man in the world.

Their grand romance is a tragic tale of immense love, sacrifice, mystery and scandal — but not scandalous for the reason one might think.

“The gender of those involved in a relationship was not in itself an issue,” associate professor of Latin at the University of Sydney, Paul Roche told news.com.au.

Homosexual relationships were not considered unusual in ancient Rome, with a man who penetrated another man — as long as he was his social inferior — perceived as behaving normally.

“However, when the ancient sources write about Hadrian and Antinous, they are concerned about Hadrian’s excessive devotion,” Professor Roche said.

“Hadrian’s excessive, passionate attachment to him was a cause of embarrassment — or a potential scandal that could be inflamed — for some Romans.”

Not much is known of Antinous before he attracted the attention of the ruler of the Roman world.

It’s estimated the young Bithynian was born in about 110, first encountering Hadrian on his travels in the Roman east in 123 or 124 and falling in love with him.

Antinous then accompanied Hadrian and his wife Sabina on their longest provincial tour of the Roman Empire, which took place over the years 128—132.

“In antiquity, Antinous is described as the emperor’s beloved,” said Prof Roche, who specialises in the literature and history of the early Roman Empire.

“Most scholars see the relationship as pederastic in the tradition of Classical Greece, i.e. love between an older man and a handsome youth.”

In the October of 130, Hadrian visited Egypt along with the imperial entourage — including his wife, and Antinous.

On a voyage up the River Nile — on the same day that locals were commemorating the death (by drowning in the Nile) of the Egyptian god Osiris — Antinous drowned.

“In his autobiography — which does not survive — Hadrian himself is said to have written that it was an accident; but others believed it was some kind of sacrifice which involved Antinous’ willing suicide,” Prof Roche said.

Malicious rumours about the circumstances surrounding Antinous’ death spread. According to Cassius Dio, the young man had agreed to sacrifice his life to ensure the emperor recovered from illness.

If he was sacrificed, it’s more likely that it wasn’t voluntary.

In ancient Egyptian tradition, sacrifices of boys in the Nile during the October Osiris festival were commonplace — with the goal to appease the gods, and ensure that the Nile flooded to its maximum capacity and fertilised the valley.

After learning of his lover’s death, the emperor’s anguish was uncontrollable — its intensity without precedent.

“Hadrian’s grief was extravagant,” Prof Roche said. “An ancient biography (The Augustan History) writes that he ‘wept like a woman’ — which is to say his grief was openly demonstrative, and lacking in the Roman male ideal of emotional self-control.”

Rather than wallow in his heartbreak, Hadrian was quick to commemorate his great love.

The small town of Hir-wer on the east bank of the Nile where Antinous died was renamed — becoming the only new city to be founded and replanned by the emperor.

“Hadrian was clearly bereaved and he had lots of images to put up,” curator of the exhibition, Hadrian: Empire and Conflict, Thorsten Upper told The Independent.

“When a city was founded close to the spot where Antinous drowned, he named it Antinopolis. It was a sort of hero-cult worship.”

Images of the young man adorned the civic buildings and the hippodrome — the whole city his memorial and shrine, and perhaps his burial place, too.

“It was still thriving in late antiquity,” Prof Roche said. “It was made a regional capital in the late third century, and a church from the late-antique period (from after the fourth century) has been excavated from it.”

Little remains of the city. The crumbled ruins of what was once a city of worship now surround the village of El-Shaikh Ebada — and local inhabitants reportedly bulldozed the remaining Roman Circus in 2015, to extend a Muslim cemetery.

Hadrian also proclaimed his dearly beloved to be a new god, risen from the Nile.

While emperors and their relatives were often deified — as was Hadrian, after his death — for a commoner to be declared divine was unprecedented.

It had never happened before — and it never happened again.

“Antinous was deified as a hero, and in some parts of the empire as a new god,” Prof Roche said.

“In Egypt, he was assimilated to the god Osiris as ‘Osirantinous’. He received a priesthood, and shrines to him were built all over the empire, especially — but not only — in the East.”

The Emperor commissioned up to 2000 statues of his deceased lover — all sharing the similar characteristics of a broad, swelling chest; head of Grecian curls; and a face always turned down.

More images have been identified of Antinous than any of the other figures in classical antiquity — with the exceptions of Augustus and Hadrian himself.

Four years after he drowned in the Nile, the cult of Antinous had spread through the Mediterranean world — with regular festivals and games held in his honour, and coins and medallions minted, illustrating his unparalleled beauty.

When the Empire converted to Christianity, many of the temples and statues built in his memory were destroyed.

At least 80 survive today — many of which are inside the Vatican museums: lasting reminders of the Emperor’s beyond-compare public memorial to his lost love.