How shame could be helping to ease Cape Town’s drastic problem

RESIDENTS were warned that if they didn’t immediately change their behaviour, the city was hurtling towards “Day Zero”. What they did was drastic.

THE trickle of water from under his neighbour’s fence certainly appeared incriminating.

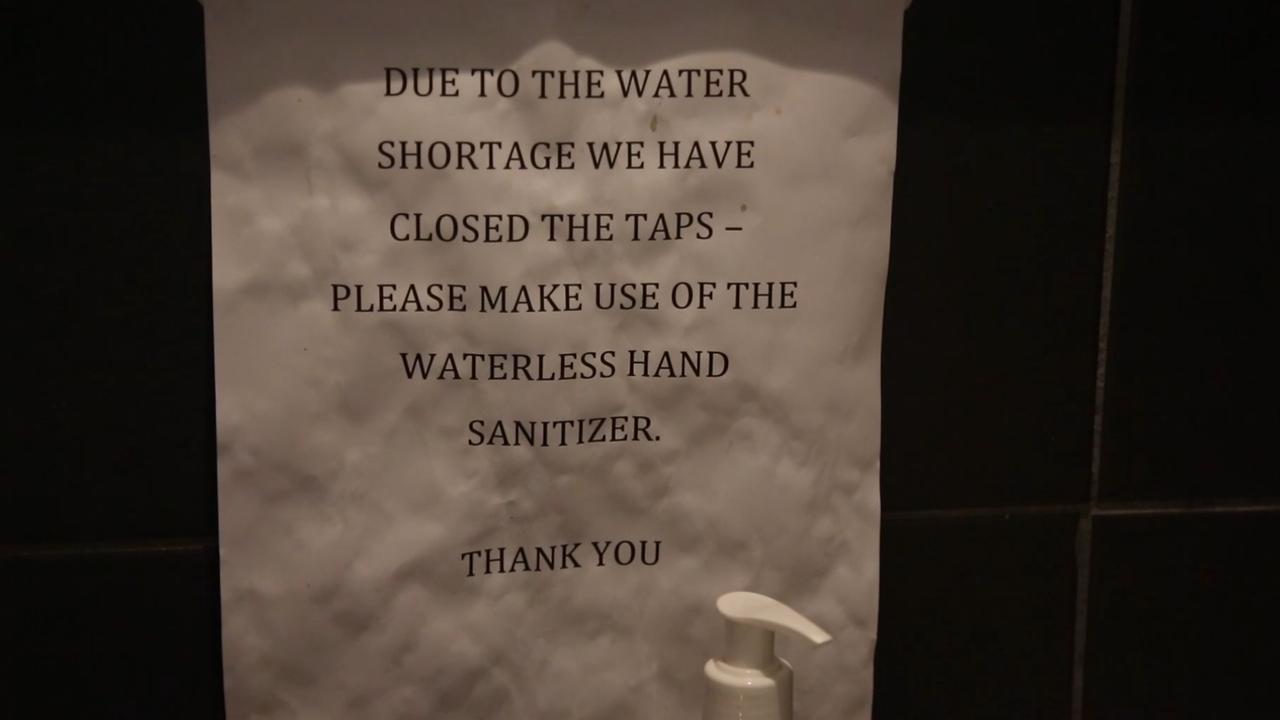

Three years into an unprecedented drought, there are harsh penalties in Cape Town for anyone using municipal tap water to wash their cars, or quench their gardens’ thirst.

So the hairdresser peered over his backyard fence and seemingly caught his neighbour in flagrante — hose in hand, a stream of water carelessly gushing over plants that had no right to look so green.

“Good morning!” he announced, meaningfully.

His neighbour looked up, startled by the intrusion. “It’s bore water!” he immediately exclaimed.

“I said, ‘Good morning’,” the hairdresser replied, deadpan.

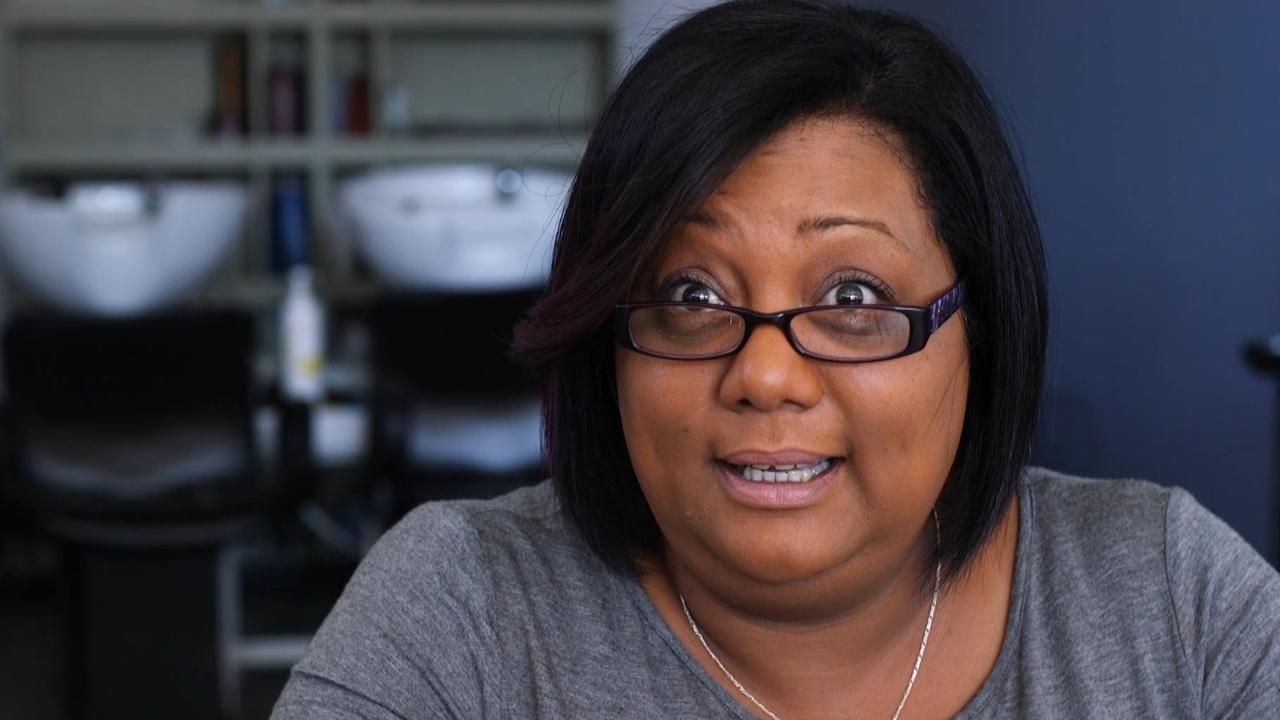

A colleague told me she’d heard this story from her hairdresser, and even though I was hearing it third-hand, the inevitable distortions no doubt creeping in, I got a strong sense of the pleasure he’d taken from a new-found (and in this case, unfounded) power to shame.

In Cape Town’s water crisis, blame quickly became a political currency as local and national governments scrambled to shift responsibility for leaving the city on the brink of catastrophe. But in the much more significant battle to persuade citizens to save water, suspicion and shame have become new social currencies.

Observatory, affectionately known as “Obs”, is a bohemian neighbourhood whose proximity to the University of Cape Town makes it popular with students and lecturers. Its wholefood shops, shabby-chic cafes and narrow streets lined with Victorian semis remind me of Newtown, in Sydney, before gentrification took hold.

It’s also home to the National Astronomical Observatory, so what better place to peer into the changing mores of its middle class residents?

During a relaxed Sunday brunch with her family, university professor Ruth Hall explains how living in a city on the verge of running out of water has transformed dinner party conversation.

“People go into long lists about what we’re doing that we never did before. It’s almost a boasting thing, like ‘How few times do you shower? How many times does your family flush the loo?’” she laughs.

“And in fact … some friends who weren’t very good at washing that frequently anyway, now hold it as a badge of honour.”

Ruth admits she “very, very seldom bothered” to wash her car. “But now I don’t even have to feel bad about it,” she says.

“You never washed your car,” clarifies her husband, David.

“OK, I never washed my car. And now I still never wash my car. But now I feel good about it — and I can frown down on all those people with clean cars!”

Social etiquette has been turned on its head in middle class and well-to- do suburbs here. A dirty car is suddenly a source of pride. A green lawn leads to suspicion. And when visiting a friend, flushing the toilet is more likely to cause offence than simply “letting it mellow”.

Cape Town imposed severe water restrictions early this year. For months, city authorities had been imploring the public to abide by the limits already in place — but only 39 per cent of residents had complied, and more drastic measures were called for.

From February 1, Capetonians were restricted to a mere 50 litres of water a day (to give you some perspective, the average Australian uses over 300 litres) and households who used too much could be fined, and have a water restriction device attached to their pipes.

Residents were also warned that if they didn’t immediately change their behaviour, the city was hurtling towards “Day Zero”, when water levels in the city’s reservoirs would fall below a critical level, and the household water supply would be shut off.

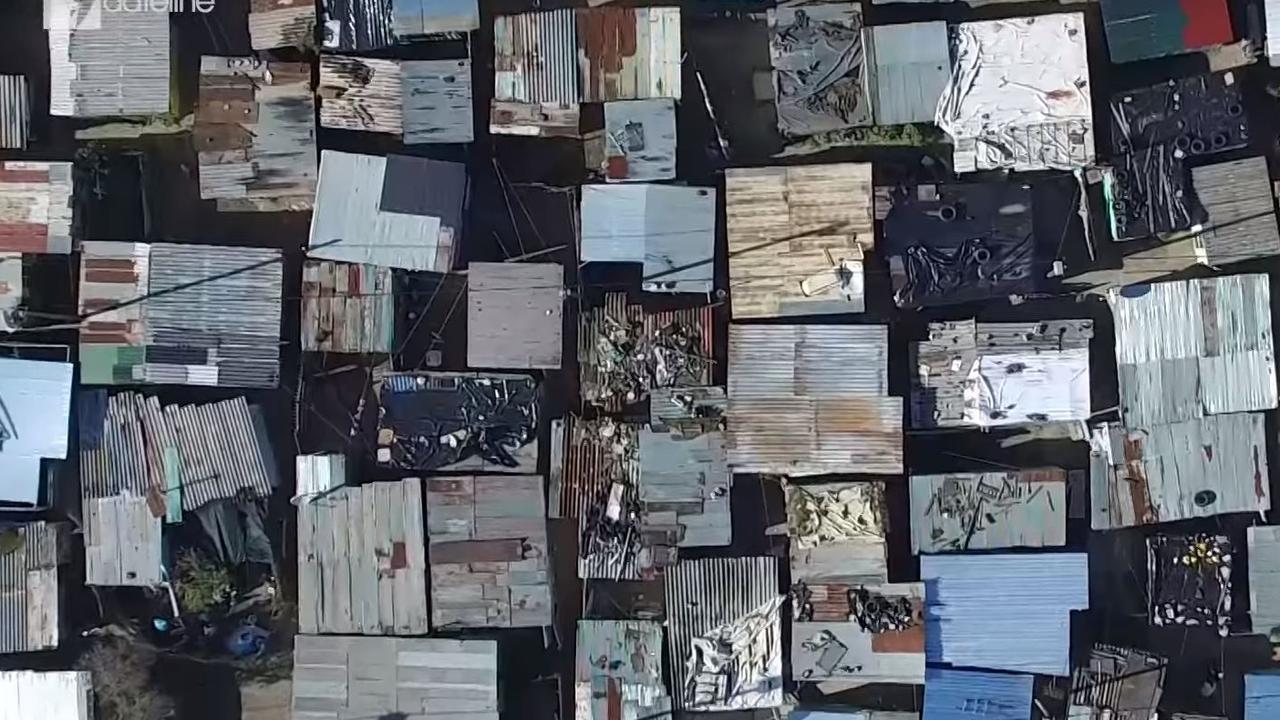

Everyone would be forced to queue at water stations for a meagre daily ration of 25 litres, raising the spectre of panic and even violence in a city with the highest rate of robbery and murder in South Africa.

But a few months later it looks like Cape Town has dodged the Mad Max scenarios — at least for now — by slashing residents’ average water use in half, an achievement the Los Angeles Times said, “dwarfs efforts in other drought-prone regions, including California.” (It went on to add that during Brisbane’s devastating millennium drought, daily water use went from 300 litres to 166 litres — “Impressive, but not as good as Cape Town.”)

Of course it’s easy to penalise people if they use too much water, and to scare them with an apocalyptic vision of what could happen when their taps run dry. But there’s more to the city’s conservation efforts than enforcement and fear.

A study by the University of Cape Town looked into how different groups responded to “nudges” or messages about saving water.

Low-income families (who’ve cut their water usage by 40 per cent) responded well to reminders about lowering their water bill. High-income families (who now use 80 per cent less water) responded best to social recognition.

The flip side of social recognition is shaming, and this was inevitable when the city made it possible for residents to compare their own water usage with friends, family, colleagues and neighbours.

“We had a staff meeting recently,” Ruth Hall told me, “and my boss put up her water usage on the board, and then everyone had to write up their own family’s water usage. It was quite a sort of shameful moment, like ‘Oh my goodness, I’m using more water than you are’.”

The enforcement of water restrictions is also driven by citizens dobbing on one another — informing the authorities if someone’s doing the wrong thing.

“I think if I did put my sprinkler on and some water went running down the drive, I think I would be reported pretty damn quickly” Ruth’s husband, David, tells me.

“And I think if I walked past somebody and they were doing that, I think I’d definitely bang on the gate and say, “Oy, what’s going on here?’”

“Community policing”, David calls it. There’s something about public shaming and informing on your neighbours that makes me uncomfortable — but perhaps that’s not a luxury Cape Town can afford. My qualms wouldn’t have saved the city.

“A little while ago I found some gardening service at my university spraying water,” Ruth tells me. “And I took photos and video and I reported them and my university quickly cancelled the contract.”

“If anyone’s cheating, we have to call them out. It’s actually a very positive thing, because I think everyone knows that we’re invested in this. We have to make it work.”

“City Without Water”, by Amos Roberts, airs on Dateline on SBS tonight at 9.30pm.