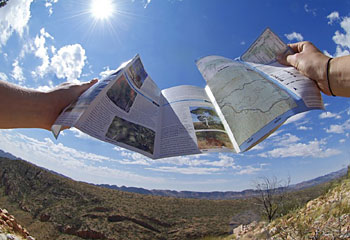

On the Larapinta Trail

BETWEEN April and September, hundreds of hikers enjoy trekking along parts of the often challenging Larapinta Trail through the West MacDonnell ranges.

THE footprint of King Neptune's ripple-sole shoe grabs my attention and makes an ancient point.

On top of a central Australian mountain range, I'm looking at a 350-million-year-old slab of rock that's grooved in even, parallel rows, much like the imprint a mythologically large ripple-sole shoe might make.

The slab, 60cm by 30cm, solidified eons ago from sand ripples on a shoreline, sits atop the West MacDonnell Ranges, 1000m above sea level. The ocean that once shaped it is 1300km away.

"It's known as ripple-mark rock," says Hamid, a geologist with whom I'm trekking the Larapinta Trail. We're on day two of a three-day desert tramp through the West MacDonnell National Park, about 100km west of Alice Springs. Hamid is an excellent companion because what are to me just rocks and boulders are soon revealed by him as exotics such as quartzite, diorite and granite. A colour consultant mightn't be a bad companion, either, since the landscape has so many shades of ochre, salmon, red and umber that they defy naming.

"Paprika rocks? Or, how about cream of capsicum soup cliffs?" proposes Jenny, a botanist and the younger of our two trekking guides. Her culinary similes are as good as any in trying to approximate the tones of this stark, vast, stony, silent landscape that, when seen from our high ridge, stretches from horizon to horizon beneath a deep blue sky.

We walk on at an easy pace, keeping up the water intake, heading west towards Counts Point ridge. Here, our lead guide Adrian calls a halt and we suck on oranges while taking in distant Mt Sonder, a mauve massif that resembles a reclining pregnant woman. Adrian points out nearby Gosse Bluff, formed when a huge comet whacked into the Earth; it was the biggest event here in the past 130 million years.

Spinifex, cycads, gibbers, skinks, kites and cockatoos: these and our footfalls are the constants as we traverse the Larapinta Trail. This chain of day walks along the ranges can be done in single sections or linked as a challenging 230km epic. Our excursion is at the moderate end of the scale, but striding past us is Thomas, a lanky young German who's doing the full trek.

He tells us: "I asked myself, 'What should I do? Get a job or take a nice 14-day hike?' Easy. I can always work later." He lopes off, the near-incarnation of that 1950s yodelling minstrel, the Happy Wanderer.

Our journey, organised by World Expeditions, consists of five walks, ranging from 4km to 16km. We camp in a mulga clearing near the ruins of Serpentine Chalet, a quixotic, late-'50s Ansett-Pioneer tourist venture. The chalet, not far from Serpentine Gorge, was once the midpoint on an all-day, bun-busting excursion from Alice to Ormiston Gorge, as endured by visitors in old war-surplus Blitz wagons. Given its remoteness on an unsealed road, it's not surprising the chalet went broke within a decade.

All that remains is a concrete slab, plus a whitefellas' midden of fibro and rusted drums, and the ghosts of tourists past. These days, on the sealed highway, it takes little more than 90 minutes to reach the once almost chimerical Ormiston Gorge.

There are eight of us in the group, plus our two guides. Our journey started with a two-hour "shake-down" walk from Alice Springs to the Geoff Moss Bridge on the bone-dry Charles River. Jenny tells me, "Geoff Moss was a minister for public works and, I think, the father of some rock guitarist, Ian Moss." You know you're getting really old when twentysomethings don't even know the name of the other (and possibly better) singer in Cold Chisel.

We pile into a Land Cruiser and head west to Standley Chasm in the Chewings Range, still part of the West Macs. Next comes a 4km loop walk. We climb staircases of shattered basalt overhung by silver-trunked ghost gums before beginning the return down the narrow, dry watercourse of Standley Chasm. This clambering descent is fun for some of us and a challenge for a couple of acrophobes. We have to wiggle through a keyhole gap, inch down a notched log, then bum-slide over boulders worn smooth by countless wet-season cataracts. Reaching the narrow cleft of the chasm, what we find flowing through it is not water but a coachload of vocal tourists.

We spend the night at our camp near Serpentine Chalet, sleeping in the open in canvas swags. Tents are an option, but no way will I miss the chance to snore at the dead centre of the continent beneath a snow-dome of stars. Nevertheless, I have to keep the swag flap pulled over my head, such is the floodlight intensity of the full moon above. The morning is near freezing but, as they say, you wouldn't be dead for quids.

Day two is the long one: section eight of the Larapinta Trail, which is about 16km. The Parks and Wildlife Service NT has marked the track well and installed water tanks at the trailheads, but there's no water up in the high desert hills. We're each carrying three litres in our daypacks, just enough to make it through an increasingly hot day.

We hoof it across rocks so old they predate vertebrates on Earth, reaching the top of the high ridge that allows us a panorama of the Heavitree and Chewings ranges as they run green, ochre and shadow-buttressed towards infinity.

"Pull up a soft rock. Let's have a break," Adrian says. We marvel at a long valley that dips between our ridge and the next one, a dramatic rise topped by a conga line of camel humps and dragon spines. Indeed, the ridges and troughs, running parallel, resemble nothing so much as giant swells on an inland ocean. Perhaps that ripple tread wasn't Neptune's but the old huarache sandal of Kahuna, god of the surf.

The earth's palette and patterns here are pure Fred Williams or Albert Namatjira. Not surprising since, as we peer through binoculars, far to the north we can make out the roofs and solar panels of the place where the latter once lived and painted, the Hermannsburg Mission, established by Lutheran priests in 1877.

The sky is a perfect blue, but the descent, from the summit's breezes into intense heat, is arduous. We're walking in the valley of the shadow of absolutely nothing. The trail's 1km marker posts seem to stretch ever farther apart. Then, finally, near dusk we reach our camp. Rest and rehydration. A fine mulga wood fire. Salad and scrumptious fish for dinner.

Lara pinta, the Arrernte Aboriginal term for central Australia's Finke River, means brackish water. The name was applied to this string of popular walks, although the Larapinta Trail is not a traditional Aboriginal route.

In 2002, Parks and Wildlife linked, upgraded and signposted the 12 sections of the trail. Between April and September each year, hundreds of hikers enjoy the various treks with professional tour operators or as well-equipped and fit solo walkers, such as Thomas.

After a warmer night, we have coffee and crumpets for breakfast, then check out the nearby dam that fed Serpentine Chalet in its heyday (if indeed it had one). At the head of a rugged valley, we find cliffs that form a chasm through which water flows in the wet season. Incongruously, right across the narrow valley is a thick concrete dam, about 12m wide by 3m high. Workers have laboured unimaginably, lugging hundreds of tonnes of cement and sand up the boulder-clotted riverbed – no vehicle could penetrate here even today – to mix and pour this massive wall. The only hint of its heroic constructors is indented lettering on the dam face: "R. Livio" and "Tessarya".

We do two shorter treks on our last day, from Serpentine Chalet to Inarlunga Pass, then a loop stroll at Ormiston Gorge. More sapphire skies framing ghost gums and the quartzite orange cliffs. More cross-country, up-hill, down-dale striding, but by now we are all much fitter and the walking is easier.

In ambulans solvitur: "In walking it is solved." Between that ultraviolet sky and the spinifex earth with its Neptune-rippled rocks, the person you meet on the trail is mostly yourself. The rhythm of paces works a mesmeric spell. We drift into our thoughts, perhaps resolving some of the petty questions of our distant, daily lives.

The walking daydream ends spectacularly when we round a bend at Inarlunga Pass and see the spectrum of the famous Ochre Pits. Vertical striations in sulphur yellow, chalk white, burned umber, deep orange and almost mulberry red are banded down the face of a 50m cliff. Aboriginal traders dug these colours, highly valued for ceremonial decorations, and exchanged them along ancient trade routes.

Our last trek, the Ormiston Gorge loop, is equally spectacular, ending beside a string of deep pools where windless waters reflect every detail of the bright ochre cliffs above. From a tiny ledge, a grey rock wallaby observes our arrival and departure back to our place, like its own, in the scheme of things.

Footnote: One of our number, Barry, a fit-as-a-fiddle trekker, legs it easily through our 30km wilderness hike, only to come a cropper over an Alice Springs gutter. He is last seen in a wheelchair sporting a sprained ankle and contemplating not Neptune or Kahuna but the gods of irony.

John Borthwick was a guest of World Expeditions.