Inside Cockatoo Island’s abandoned reformatory for girls, Biloela

WELCOME to hell on earth. For years, this island was a youth detention centre for girls. Awful things happened there.

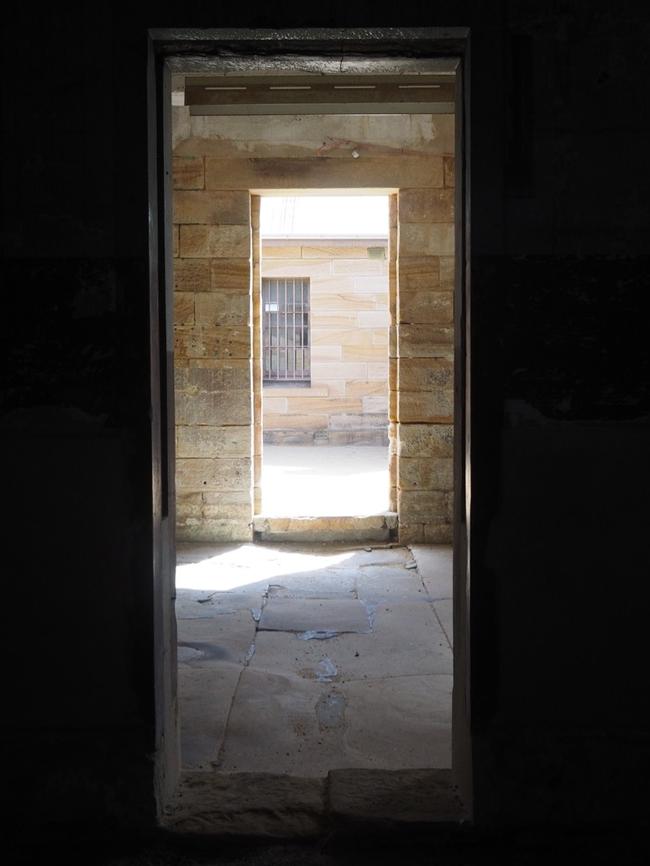

IT’S pitch black inside this dank cell. The wind howls through the walls. I can’t see a thing.

The rooms within this abandoned detention centre for girls are like something out of a horror movie. The isolated nature of the place hits me with every breath I take.

The only sound that echoes inside these thick sandstone walls are my footsteps, gaining pace as I look for a way out of the cold buildings that once made up Biloela — an institution that housed a congregation of abandoned and delinquent girls.

I’ve come to this windswept hill on Cockatoo Island in the middle of Sydney Harbour to visit the facility that was once home to nearly 100 girls. The institution was split into two parts: the Biloela Public Industrial School for Girls and The Biloela Reformatory — the reformatory was for girls who had broken the law, while the industrial school was intended to operate more like an orphanage.

Little girls, some as young as six, were locked up inside these buildings — many had committed no crime other than having no parents. As darkness falls I listen carefully and can almost hear them crying.

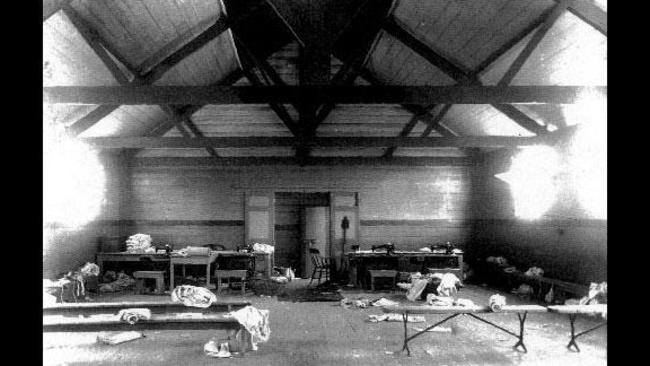

Stories abound. When the institution was inspected during a Royal Commission into Public Charities in 1873, Biloela was found to be a dysfunctional organisation, where inmates were forced to work in sweatshop conditions and suffered harsh, arbitrary punishments.

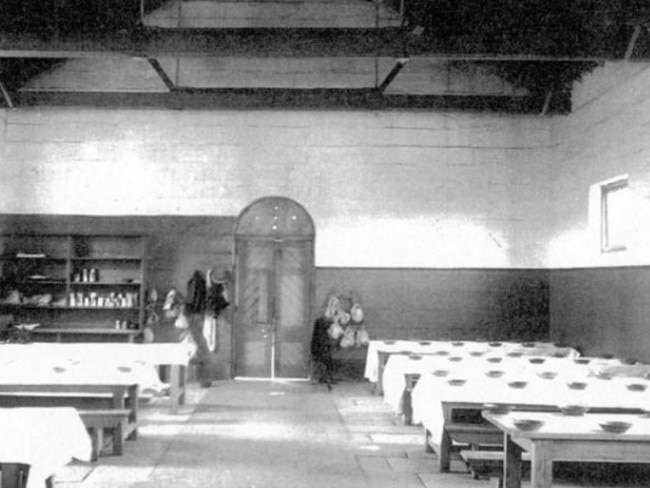

“The girls lapped water from a common trough and were not given cutlery to eat with,” the commission found.

“They were locked in the gloomy jail cells for twelve hours a night with nothing to occupy them.”

The report detailed an incident where the superintendent, George Lucas, took away the girls’ beds as punishment, making them sleep on the cold stone floor. Many of the girls were found to have bruises and lacerations. The testimony of 14-year-old Katie Solomon is illustrative of how frightened the girls were of Biloela’s superintendent and his wife Mary Ann, the institution’s matron.

“Mr Lucas came into the dormitory and saw some figures on the wall. He was very angry about them, and caught me by the hair of the head and told me to rub them out. I said I should not,” the report reads.

“He then dragged me down, and put his foot on my back and stood on me. He knocked my head against the wall, and said he would take my hair to rub the figures out with it. Annie Smith, Janet Boyd, and Mary Windsor were beat very badly ... I was kicked on the hop, and I have the mark on the place to show ... I got that mark on my face when he hit my head and rubbed it against the wall.”

Many newspaper articles from the time also report on the dreadful conditions endured by the girls.

“On opening the door of the dark room, eight girls, from 14 to 17 years of age, were found, four of them in a half-naked condition, and all without shoes and stockings,” the Brisbane Courier Mail reported in 1879.

“Their wild glare and half-crazed appearance as the light of the opened door fell upon them struck us with horror.”

Some years prior to Biloela being established, shipbuilding began in earnest on Cockatoo Island. There was also a training ship, the Vernon, that was anchored off the island. It was intended to teach up to 500 wayward and neglected boys nautical skills.

Obviously, placing a facility for girls near workshops where thousands of boys and men toiled each day would have been a recipe for disaster.

In 1874, English social reformers Florence and Rosamond Hill visited the island and noted the absurdity of the location of Biloela.

“The building allotted to the school had obtained a terrible notoriety as a convict jail. The home influences essential to the wholesome training of girls, the very lack of which had brought them to the school, are impossible of attainment within the gloomy walls of a prison,” they wrote in What we Saw in Australia.

“Not only did the evils described attach to the locality, but the Government dock, bringing necessarily large numbers of sailors to the spot, is upon the Island.

“Three hundred men, we heard, had been there a few days before our visit. The school premises are on high ground overlooking the dock, from which they are divided by a low wall or fence, and the presence of a policeman is necessary to prevent sailors and schoolgirls from crossing the boundary.”

The island is located only one ferry stop from Circular Quay, in the heart of Sydney, yet feels a world away. It’s a far cry from the typical urban sprawl of the city. Here, blue surrounds the 12 hectare circle of land, that is now articulated by man-made cliffs, stone walls and steps. Fortunately, the buildings of the island’s jail, that were allotted to Biloela, were never demolished. Instead, its memories and items inside, were left to rot.

I fumble my way around the convict precinct and find the mess hall, where the girls would have filled the room with their chatter, screams and tears. One can only wonder what went on inside these walls. It’s both a scary and compelling experience.

Now this setting has transformed from a place of pain and agony, to one of reflection and beauty.

IF YOU GO:

Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour is open to the public daily. It’s a 10 minute ferry ride from Circular Quay.

The island is the only harbour island where you can stay overnight — it has a unique offering of accommodation options to suit all budgets. Visitors can camp, “glamp” (in weatherproof safari-style tents on raised platforms), or stay in large heritage houses or apartments.

For more information go to www.cockatooisland.gov.au.

Continue the conversation on Twitter @newscomauHQ |@LeahMcLennan

* The writer was a guest of Cockatoo Island and the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.