Fraser Island on foot

ENJOY the silence, the scenery and ethereal atmosphere on the Fraser Island Great Walk across the largest sand island on earth, writes Susan Gough Henly.

I PAUSE for a moment amid the silence of the rainforest to admire a soaring straight-trunked Queensland kauri pine, a timber prized in the logging days for sailing ship masts. Looking down, I gasp, having momentarily forgotten these massive trees grow in fine sand.

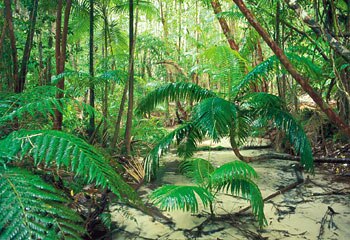

The creamy silica of the forest floor not only lightens a canopied world of ancient ferns and delicate orchids hidden among green mosses but makes for a cloud-like softness underfoot.

Strangler figs are draped in vines and bright orange fungi sprout from rotting tree trunks, their fine threads slowly decomposing the wood, all of which adds nutrients to an entire ecosystem that exists without soil.

Walking is the best way to savour Fraser Island, the largest sand island on earth, lush with pristine freshwater lakes, vibrant coloured-sand cliffs towering over rugged ocean beaches and dense forests growing in dunes up to 200m high.

Fraser Island is the remnant of a sand mass that once stretched 30km east into the Pacific Ocean. As sea levels rose and fell, episodic dune building formed a sequence of at least eight overlapping dune systems of different ages, some more than 700,000 years old, the most ancient recorded sequence. A succession of plants and trees sourced nutrients that collected in the sand until they grew to the size of giants.

One of the absurdities of exploring this World Heritage Wilderness Area by four-wheel-drive is that the essence is lost in the noise of the modern world. In contrast, everything we see at our humble walker's pace is a tiny clue to a remarkable landscape that was formed through millenniums with the shifting of millions of grains of sand.

The 90km Fraser Island Great Walk is a multi-million-dollar initiative of the Queensland Government and is set to redress the natural balance in one of the world's most remarkable settings. Better yet, since it is largely at sea level, the walk is moderate and easy.

With our tents, stove and food in backpacks, we board the Kingfisher Bay ferry at Urangan Harbour and relax on the hour-long trip to Kingfisher Bay Resort. To our delight, several humpback whales breach in front of us and a couple even come alongside the boat. We could spend up to eight days doing the complete walk from Dilli Village to Happy Valley but, since we only have four, we decide to bookend our walking and camping adventure with nights at the award-winning Kingfisher Bay Resort, which offers forays in the environment with champagne trimmings. It makes for a good mix.

Kingfisher Bay is large, with 152 rooms and 110 villas built up the hill overlooking the bush and Hervey Bay. It nestles gently into the heath, wallum forest and melaleuca wetlands. With several swimming pools, tennis courts and restaurants as well as a range of watersports activities on the bay, there is no shortage of relaxing options. Even more significantly, given its location, there is an impressive ranger program and we have trouble making a choice about what to see and do.

We decide on a guided canoe trip to explore the Great Sandy Strait (declared a wetland of international importance under the 1971 Ramsar Agreement) and the mangrove creek colonies, and are lucky to see a dugong in the sea grasses as well as a pod of bottlenose dolphins breaking the still waters of the strait.

Before dinner we go on a guided bush tucker walk where we spot many of the ingredients that will later feature in our meal at Seabelle restaurant in the dramatic main building, its curving timber walls designed to reflect the rolling sand dunes.

Next morning we are dropped off by taxi to start our walk at Lake Boomanjin. We set off along the well-marked track, finally free of the noise of car engines. The silence is palpable, pricked from time to time with the call of a tiny bird high in the treetops.

We stop to marvel at this remarkable perched lake, the largest of its kind in the world, in its shimmering, peaceful splendour. A perched lake is formed in sand dunes above the water table when sediment collects at the bottom of the dune and acts as catchment for rain water. Indeed, Fraser is home to half of the world's perched lakes. Some, such as Boomanjin, are stained a golden brown by the tannins of the surrounding melaleucas while others are so clear you can immerse your hand and see it as clearly as if no water were there at all.

We leap across honey-coloured streams flowing across the sand before following the track past scribbly gums, the curious scribbles on the bark made by the scribbly moth caterpillar. Part of the appeal of the walk is to catch glimpses of the island's past, such as carved-out canoe trees from the earliest Aboriginal inhabitants and markers from the logging days. Up the sandy slope, the vegetation changes to thicker rainforest of kauri pine, vines, staghorns, palm lilies and mosses. Fraser is home to masked owls, yellow-tail black cockatoos, swamp wallabies and eight kinds of well-camouflaged tree frogs. Only the cockatoos make their presence known, screeching in the sunshine above the canopy.

We reach the walkers' camp set back from the clear waters of Lake Benaroon as an early winter dusk falls. The perfect time to walk on Fraser is from June to October, during the balmy subtropical Queensland winter and spring, not only because there is no humidity or bugs but this is humpback season in Hervey Bay.

The campsite has a pit toilet and numerous tent spaces. Two tent sites share a low picnic table and large metal dingo-proof box in which to store all food. The dingo issue came to a head a few years ago when a young boy was mauled to death on Fraser. Today, a huge amount of effort in terms of education and prevention has been put into practice. All the hikers' camps have metal food storage boxes and some campsites, such as at Lake McKenzie, have been completely fenced to keep the dingoes at bay.

During our stay on Fraser the only time we see a dingo is when one strolls through the outdoor pool area at dusk at Kingfisher Bay Resort. At all times it is essential to have no contact with these wild dogs. They are naturally scrawny and should never be fed.

After a hikers' feast cooked on our camp stove (no open fires are allowed at any of the six hikers' camps), we stroll along the shores of Lake Benaroon, where the still waters glisten under a full moon. The next morning we pass foxtail sedges lining the adjoining Lake Birrabeen and continue along an old logging road overhung with banksias.

As we climb, we enter the tall forests of the central high dunes including the enormous satinay hardwood trees; their not-so-fortunate relatives line the London docks and Suez Canal.

A couple of hours later we descend into historic Central Station, a popular walking hub with a small museum, picnic facilities and a boardwalk over Wanggoolba Creek, where crystal clear water flows over pure white sand. On either side of the creek, satinay and brush box trees and airy piccabeen palms are festooned with crow's nest ferns and staghorns and the hefty angiopteris ferns, which have the largest fronds in the world.

They all lend an ethereal atmosphere to what was once the centre of the timber industry on Fraser. Selective logging resulted in some of the tallest trees now being found near Central Station. With the banning of logging and sandmining, these trees have been saved and have the nutrients to thrive.

After lunch we stop at freshwater Basin Lake for a swim. We see several small turtles in the clear water as white-bellied sea eagles soar overhead. It is marvellous to lie out on the powdery white sand with no sticky salt on our skin. Refreshed, we walk the final kilometres through open woodland and lush melaleuca wetland, filled with lime-green reeds that catch the sun's slanting rays.

Lake McKenzie, aptly nicknamed the Blue Lake for its brilliant aquamarine tint, is ours alone at dusk. In the middle of the day it could be on the Gold Coast, with hundreds of daytrippers sunning themselves as tour operators prepare their lunch. As walkers in a different time frame, we have experienced Fraser as it was meant to be enjoyed.