Drought uncovers drowned town

AUSTRALIA'S worst drought in a century has uncovered a town deliberately flooded 50 years ago as part of a massive hydro-electricity scheme.

AUSTRALIA'S worst drought in a century has uncovered a town deliberately flooded 50 years ago as part of a massive hydro-electricity scheme, stirring painful memories for former residents.

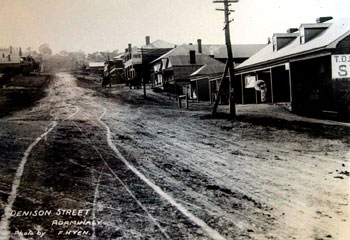

Adaminaby, a small farming town nestled in the Snowy Mountains on the border between New South Wales and Victoria states, was submerged under 30 metres of water in 1957 when the local valley was dammed to form the man-made Lake Eucumbene.

The settlement was never expected to be seen again but the severity of the drought has evaporated most of the lake, bringing it back to the surface.

"We couldn't believe it when the old streets started to reappear," said Leigh Stewart, a local history buff who grew up in the old town and once ran a shop there.

"It brought back a lot of memories, I can still see in my mind's eye how the town was," he adds, gesturing around the muddy wreckage of what was once his family home.

Stewart said the town's re-emergence was a striking demonstration of the severity of the drought.

"It shows how bad the situation is around here," he said.

"The dam's at about 20 per cent capacity now and it's getting worse. We're all hoping it turns around soon and we get some consistent rains that will fill the lake again."

The hills around the lake are topped with green vegetation that stops abruptly at a line mid-way down the valley, replaced with brown mud that marks the old shoreline, some 30 metres above the current water level.

Main street now above water

The sloping main street of the old town, its bitumen eroded from decades underwater, is now being used by locals as a boat ramp to access the depleted Lake Eucumbene.

Shards of pottery, rusted batteries, bottles and other remnants of everyday life in the old town dry in the sun, with the foundations of old houses covered by a thick layer of silt from what used to be the bed of the lake.

The blackened skeletons of trees drowned half a century ago poke out from the water about 50 metres from the current shoreline in a straight row, still marking the route of a road they once lined in the old town.

A flight of concrete steps leads up to the remains of the St Mary's Catholic Church, now reduced to a few tilting brick columns and rotten wooden floorboards.

It was at the top of these stairs that Greg and Mary Russell were sprinkled with confetti when they were married 60 years ago.

Greg, now 82, said he had mixed feelings wandering the streets in the old town where he played as a child.

"It's sad and it makes me a bit nostalgic," he told AFP. "We had some good times there and it's strange to see it this way now."

"They said it was for the good of the nation"

The creation of Lake Eucumbene was one of the largest projects in the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, a huge post-war engineering project designed to harness the power of the Snowy River.

The scheme involved building seven power stations and 16 dams, linked by 145 kilometres of tunnels through the mountains and 80 kilometres of viaducts.

More than 100,000 workers were involved in its construction, many of them refugees from war-ravaged European communities whose arrival permanently altered Australia's demographics, diluting the predominance of those from British roots.

Tiny Adaminaby, a hamlet of about 700 people, stood in the way of the ambitious nation-building project and policy-makers in Canberra decided it must be sacrificed in the name of progress.

"We were told we had to move," said Anne Kennedy, who was still a child when her home was flooded.

"A lot of us never wanted to go, my father tried to chase them down the street with a gun, but they said it was for the good of the nation and we had no choice in the matter."

A contemporary photograph taken at the ceremony to mark commencement of the dam's construction shows the townsfolk dressed in their Sunday best, their sombre, worried expressions contrasting with the official bunting and celebratory placards.

More than 50 buildings from the old town were moved nine kilometres away over a hill to the town that now bears the name Adaminaby.

Some timber houses were simply lifted onto the back of trucks and driven to the new settlement, others such as St John's Church of England were dismantled stone-by-stone and rebuilt.

A sense of betrayal

Kennedy said only about 250 of Adaminaby's residents resettled in the new town, the rest took compensation packages they regarded as woefully inadequate and moved elsewhere.

She said the town, which had once been a thriving local hub, struggled as its regional rivals prospered with the development of ski-fields and other tourism attractions in the area.

Many locals developed a deep mistrust of outsiders because they felt they had been betrayed when their community was relocated, she said.

"We had an influx of new people a few years ago who bought retirement homes here," she said. "People weren't very welcoming because they didn't trust outsiders after what happened with the relocation. Adaminaby was starting to get a reputation as an unfriendly place."

Kennedy's solution was to begin work on a huge quilt showing the town's history that involved all members of the community working together in the local town hall for two years.

She said the plan successfully brought the community together and the re-emergence of the old town now also gave displaced townsfolk a chance to come to terms with the past.

"It lets people say goodbye to the old town because they never really had a chance to do that originally," she said.

She was also hopeful the ruins of the old town could become a tourist attraction to bring visitors to modern Adaminaby.

"Who knows?" she said. "At least it would mean something good came from all of this."