NASA to test-launch its next manned space vehicle, Orion

IT’S NASA’s dramatic return to the space race. But will this week’s test launch of a new spaceship designed to carry men to Mars go to plan?

IT’s NASA’s dramatic return to the space race. But will this week’s test launch of a new spaceship designed to carry men to Mars go to plan?

It’s got a lofty name: Orion — the huntsman god.

It’s more than a passing throwback to NASA’s most successful space program: Apollo — the sun god — which took man to the moon.

Gone is the sleek aerodynamic form of NASA’s reusable space shuttles.

It’s nothing like what we’ve seen in Insterstellar, Star Trek or 2001: A Space odyssey.

SEARCH FOR EARTH2.0: 1800 planets. Nine contenders. The hunt is on

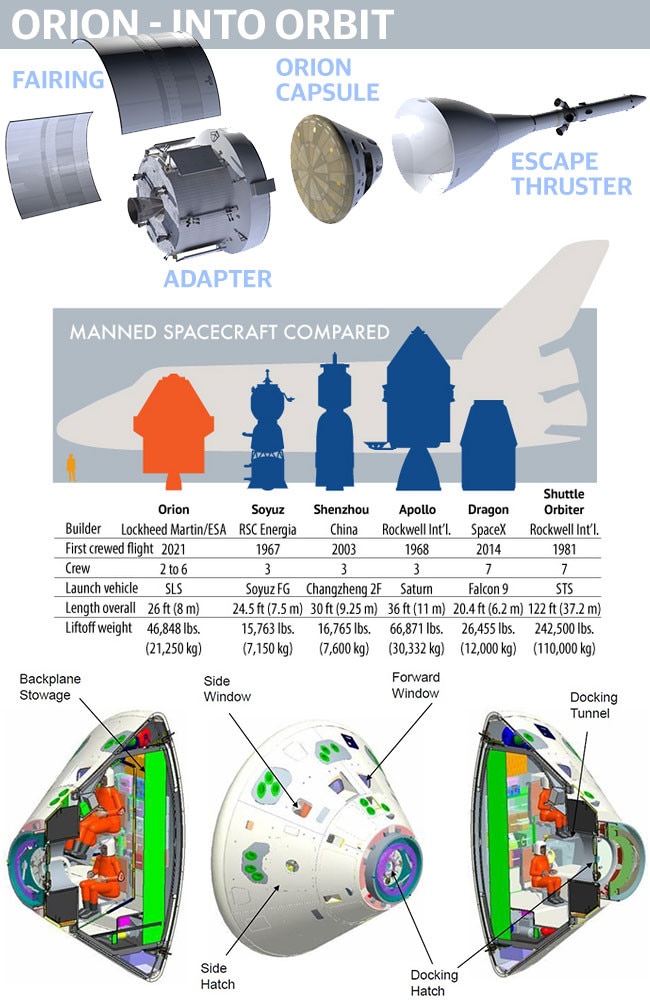

With its cone-shaped command vehicle, it’s a case of back to the future for the Orion (EFT-1) command module. It is expected to become the standard ride for astronauts for the next 30 years.

Crunch time for the 5m wide, 12,337kg vehicle’s future is 11pm Thursday (AEST).

If you think the explosion of the Antares cargo rocket on launch in October was spectacular; the devastation would be many times greater if this one were to go wrong. The fallout for NASA would be nothing short of catastrophic.

The Delta IV they are pinning their hopes on is the world’s most powerful rocket, producing 900,000kg of thrust. The use of the reliable old workhorse represents how the Orion project is already drifting off course. Orion was supposed to be carried by an even more powerful booster: the Ares. That program has been cancelled.

PLANET X? New clues have astronomers searching beyond Neptune

But the Orion capsule’s existence represents a return to manned spaceflight for NASA and an end to reliance upon an increasingly reluctant Russia for a taxi service to the International Space Station (ISS).

The EFT-1 test will only last 4.5 hours, but what we learn could change history forever. #Orion #JourneyToMars pic.twitter.com/aErgrFlVye

— Lockheed Martin (@LockheedMartin) November 25, 2014If all goes well, NASA will be able to boost four astronauts at a time into Earth’s orbit — and beyond. The old Apollo could only carry three. The shuttles could carry up to eight, though not lift them anywhere near as far into space

The four-and-a-half hour test flight will send the unscrewed Orion module around the Earth for two orbits at a height of 5800km — 15 times further out into space than the ISS. No human has travelled that far in more than 40 years.

ORION: THE MODULE

It’s survived a decade of cutbacks and budget uncertainties. But does NASA’s economy-class return to manned spaceflight have what it takes to explore our solar system?

It looks the part. Anyone around long enough to remember the Apollo moon program will recognise its basic design. So will those who’ve browsed through the history books.

Meet Doug. He is the Lead Manufacturing Engineer for the #Orion Crew Module Uprighting System Tanks. #EFT-1 pic.twitter.com/DUaV1wpUqz

— Aerojet Rocketdyne (@AerojetRdyne) November 24, 2014But the old-fashioned shape says something for NASA’s limited ambitions: After the failure of several extremely expensive shuttle replacement designs and an even bigger “son of Apollo”, the Constellation program, it needed something that would work. And fast.

Meet Jennifer. She is Program Manager for the #Orion Crew Module Reaction Control System. #EFT1 pic.twitter.com/WOauslRyyv

— Aerojet Rocketdyne (@AerojetRdyne) November 26, 2014While any manned mission to Mars will likely involve the Orion command module, it will come with some “optional extras”. The module itself is simply too small. It would need a caravan-like attachment to provide vital accommodation space and life-support facilities. Not to mention a trailer-full of landing craft and fuel.

Meet David. Program Chief Engineer for the development of #EFT1 #Orion Crew Vehicle Reaction Control System. pic.twitter.com/A8lZDees0M

— Aerojet Rocketdyne (@AerojetRdyne) November 25, 2014“This is the next step on our journey to Mars, and it’s a big one,” said William Gerstenmaier, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration and operations.

“Orion will travel farther than any spacecraft built for humans has been in more than 40 years. That’s a huge milestone for NASA, and for all of us who want to see humans go to deep space.”

Kick the tyres and light the fires: The $7 billion contract to design and build the manned module was awarded to Lockheed Martin in 2006. Their task was to prepare for three manned missions before 2020.

.@NASA_Orion's interior measures 314 cu ft inside = About 2 minivans. #JourneyToMars http://t.co/fxSHqDqP0h pic.twitter.com/VVFlFxXfew

— Lockheed Martin (@LockheedMartin) November 24, 2014Under “the hood”, Orion is very different to Apollo. It’s 30 per cent wider, resulting in twice the interior space. It comes with a toilet as standard instead of the original plastic bags …

It’s also full of flat-screens and big switches: Computer technology having advanced considerably in the past 40 years. Even your smartphone has far more computing power than the original Apollo.

Caution: Rough road. Sneak peak of the human #spaceflight owner's manual: http://t.co/AzcOJJ3iGs pic.twitter.com/vdDfvnbkvW

— Lockheed Martin (@LockheedMartin) November 26, 2014All this hi-tech comes at a price: To protect it (and the astronauts) from the sun’s radiation, considerable quantities of shielding have had to add to the module’s weight.

Enhanced safety: Orion’s also designed to be strong enough to survive a catastrophic launch failure: Internal systems are intended to give it a “kick” up and away from a burning booster so it can deploy its parachutes from a safe distance.

Meet David. He is the Chief Engineer for the #Orion Launch Abort System Jettison Motor. #EFT1 pic.twitter.com/r3QqvB7ZYw

— Aerojet Rocketdyne (@AerojetRdyne) November 26, 2014And, as a lesson learned from the Shuttle disasters, all its on-board controls have been designed to be easily operated by crew wearing their bulky and clumsy spacesuits.

And remember the major plot point of Apollo 13? The problem with finding a replacement filter to fit the carbon dioxide scrubbers? Well, this time things are a bit more sophisticated. The CO2 is stored and can be vented into space. Fire is also less of a risk as the air in the module has a lower concentration of oxygen.

Like Apollo, Orion is designed to “splashdown” in the ocean upon its return to Earth. This has more to do with weight savings than safety.

Preview of @NASA_Orion Launch from @NASAKennedy on Dec 4th Thx @NASA @LockheedMartin and @ulalaunch Big #STEAM 🚀🌎🔠http://t.co/pYU1mltjho

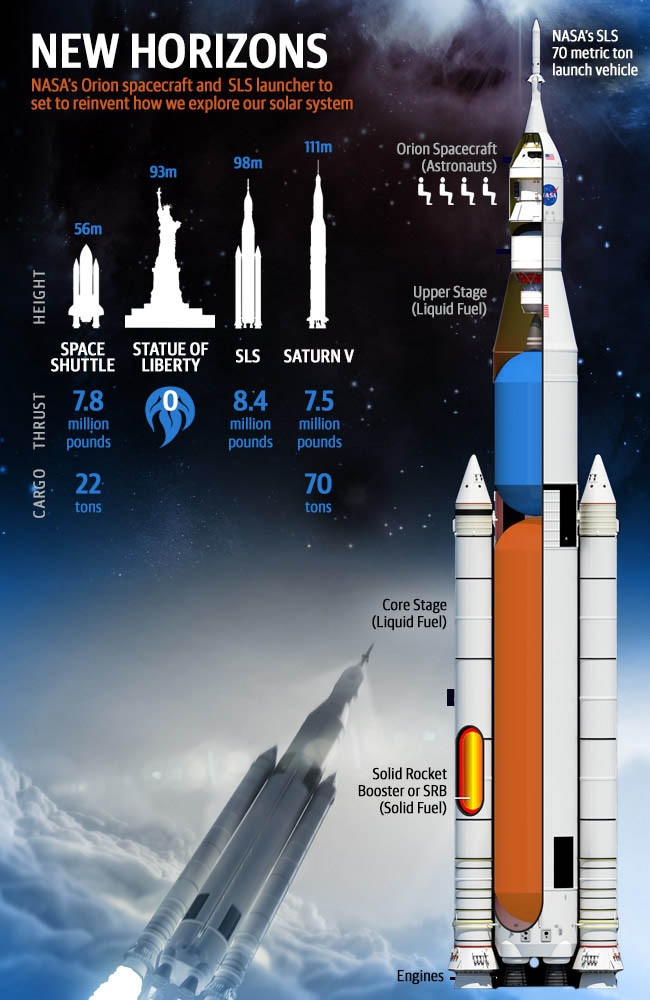

— Leland Melvin (@Astro_Flow) November 30, 2014Giving Orion a boost: NASA has to wait until 2018 before a rocket capable of allowing the Orion capsule reach its full potential, the Space Launch System (SLS), is ready to go. Initially it will be able to boost a 70 tonne payload into space. Later versions are expected to carry 130 tonnes. Such heavy lifting potential is vital if a manned mission was to ever head for Mars.

THE TEST FLIGHT

The module being launched this week is regarded as fully flight-worthy. It’s just not carrying any crew as a matter of precaution, for any unexpected oversights.

“Before we can send astronauts into space on Orion, we have to test all of its systems,” NASA engineer Kelly Smith said. “And there’s only one way to know if we got it right — fly it, in space.”

It is currently sitting some 61 metres above the ground at Cape Canaveral, atop the Delta IV’s thin metal casing packing hundreds of tonnes of fuel.

#Orion's EFT-1 is more than a test. It's the first giant leap in the next space age: http://t.co/y7RRUGbNLs pic.twitter.com/pDUBzJl84W

— Lockheed Martin (@LockheedMartin) November 28, 2014Stacked together will be the Orion Command Module, a service module, the module’s emergency abort system and an “adaptor” which connects these utility components to the heavy rocket itself.

They’ve were all hoisted into place more than a fortnight ago.

It’s due to launch at 7am US Eastern time on December 4 (11pm AEST) — weather permitting.

Instead of people, it’ll be carrying masses of sensors to record every element of the flight. Some of it will be beamed back to mission control. Most will be stored on-board to be retrieved after the capsule is recovered.

On Dec. 4, watch NASA TV for live #Orion mission coverage from launch to splashdown and everything in between. pic.twitter.com/ofWdZ7AO1H

— Johnson Space Center (@NASA_Johnson) November 25, 2014Phase 1: This is the “boost” phase which lifts the Orion capsule and its attendant modules some 160km above the Earth. At this point the capsule will be moving some 2700km/h.

Phase 2: The assembly of protective panels and adaptive modules which connect the Orion and its service module to the Delta IV launch rocked should detach, leaving the command module clear to fly further into space.

Phase 3: If Orion successfully separates from the Delta IV rocket, it will be boosted further into space out to a total distance of 5800km. This is regarded as the most critical phase of the test flight. Orion is expected to pass through the Earth’s Van Allen belts — bands of radiation which protect us below from the sun’s deadly emissions. This will test the on-board electronics’ ability (as well as that of any future fleshy crewmen or women) to cope with the rigours of interplanetary spaceflight.

Phase 4: Once Orion separates from its second boost module, it begins its journey back to Earth. On-board computer systems will place the command module at an ideal angles for entering the atmosphere.

Phase 5: Ripping through the Earth’s atmosphere will generate superheated plasma of some 2200C as it slows from its 32,000km/h space travel speed. Will its shields hold out? Naturally, NASA and Lockheed expect so. Once used, this shield should detach.

Phase 6: Orion still needs to slow from the 480km/h it is expected to be travelling at. With parachutes deployed in various stages as speed brakes, Orion will also be angling for a safe splashdown.

Phase 7: Bobbing among the waves, the US Navy amphibious assault ship USS Arlington should be able to hoist the Orion module aboard.

What’s next? Orion and its future rocket launcher, the SLS, has to survive further US government cutbacks as the economy which once sent men to the moon continues to contract. With the much-touted rise of commercial space ventures, such as Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic Galaxy project (which crashed) and the Orbital Sciences project (which blew up), more and more US politicians are expressing doubt as to the need of an expensive government-funded space program.

We're 1 week from launching @NASA_Orion on it's 1st flight. Watch the flight test unfold on NASA TV on Dec 4. #Orion pic.twitter.com/apEZHgwonm

— NASA (@NASA) November 27, 2014