Beacon of Galaxy message attempts to make contact with aliens

Scientists propose sending out a message for aliens with directions to help them get to Earth.

Scientists are developing a new transmission to send out into the stars to let aliens know where we are.

While the proposed message, named ‘The Beacon in the Galaxy’ (BITG), will not be the first humans have sent into space, it will have more information on the human race then any that have gone out before. Including directions on how to find us.

Astronomer at Swinburne University and Director of the Space Technology and Industry Institute, Associate Professor Alan Duffy, told news.com.au’s podcast I’ve Got News For You that the new message was an advancement on previous efforts to contact extraterrestrial life.

“It’s going to be a more powerful telescope, or in fact, two telescopes that will send the signal,” he said.

“We think it’s a clever message that comes with more information and still should be reasonably easy to decipher. It’s also being sent towards a target that we have reason to hope at least, may have aliens.”

While scientists have yet to decide whether they will send the message into space, the message would be transmitted from both the 500 metre Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope in China and the SETI Institute’s Allen Telescope Array in northern California. The transmission will be targeted at a selected region in the Milky Way galaxy, which has been proposed as the most likely location for life to have developed.

“It’s towards the centre of our galaxy and it’s a dense collection of stars where we think that they’ve had a longer time to have potential life,” Professor Duffy told I’ve Got News For You.

“That denser number of stars means there’s more potential places for life to arrive, but also the fact that they’re older stars than our own means there’s been more time for intelligent life to arise as well.”

The message itself was designed by a NASA-led team with international contributions. The concept was to make the language as simple as possible so that the aliens could decode it.

“The one thing we think is universal is mathematics,” said Professor Duffy.

“Using mathematical framing you can begin to build up a bit of a dictionary, a sequence of ones and zeros, bits that computers read.”

The BITG message is proposed to be sent as a beamed radio wave coded in binary. Any mention of human language and culture will be excluded from the message in favour of more universal concepts such as physics and biology. Information on human DNA as well as the fact that we are bipedal, meaning we have two legs will be included.

More controversially Professor Duffy said information about the location of the Earth will be included.

“We do that by what we hope is a pretty obvious global signposting, or at least a cosmological signposting with a known globular cluster,” he said.

A globular cluster is a tightly bound cluster of tens of thousands of stars bound by gravity in the shape of a sphere. The message maps our position to nearby clusters with the hope that intelligent life will figure out the map.

Should the message ever leave the planet, it will not be the first. The first was sent back in 1974 from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. It described the basic chemical makeup of the DNA molecule, as well as sketches of a human being and our solar system. It was targeted at a cluster of stars over 25,000 light years away and as such will not be arriving any time soon. Since then plenty of other messages have been sent including the Beatles song ‘Across the Universe’, a Doritos advertisement and an invitation in the fictional language Klingon from Star Trek to a Klingon Opera in the Netherlands.

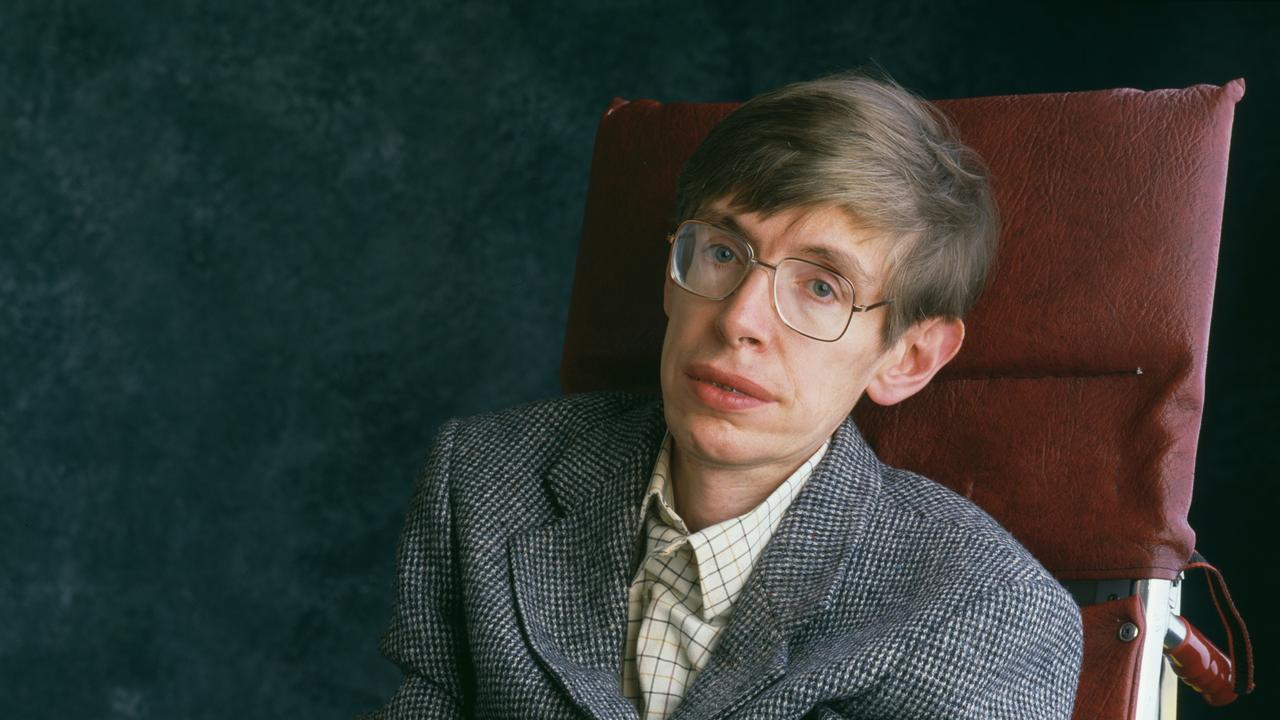

This is the first message, however, that will provide a map to help aliens get to Earth. So clearly broadcasting the position of our planet is not without controversy. Over a decade ago Professor Stephen Hawking was adamant in his belief that making contact with advanced alien life will probably not work out so well for humans.

“If aliens visit us, the outcome would be as much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn’t turn out well for the native Americans,” he said.

“Such advanced aliens would perhaps become nomads, looking to conquer and colonise whatever planets they can reach.”

The researchers heading the BITG project disagree. Lead researcher, Dr Jonathan Jiang at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California wrote in a preliminary paper yet to be peer reviewed that the advancements of science should contact be made would vastly outweigh the concerns.

“A species which has reached sufficient complexity to achieve communication through the cosmos would also very likely have attained high levels of co-operation among themselves and thus will know the importance of peace and collaboration,” he wrote.

Professor Duffy is also uncertain whether the message should be sent. He argues that while we can’t assume any aliens are going to be benevolent beings, by sending out the message, scientists today are making a decision for the rest of humanity.

“You’ve made a call for all time, you can’t take back that message,” he said.

If any nasty aliens with intentions of colonising the Earth do happen to receive the message, it would take tens of thousands of years for them to even reach us, not to mention the thousands of years it would take for the message to reach its destination.

Despite all the work that’s gone into the transmission, Professor Duffy doesn’t think there’s any real need to send it.

“Any intelligent civilisation that’s more advanced than us … are going to know we’re here already,” he said.

“We are already sending out signals into space with our radio and TV signals. Radio has been transmitting for over 100 years now.

He does acknowledge that the two telescopes in China and California will send a significantly stronger transmission than our average day to day frequencies.

“I think that [the concerns] should give us all pause for thought and maybe to reconsider sending the message, but I do love the fact that we think about what the message itself should be.”

Listen to the rest of the interview with Professor Alan Duffy on I’ve Got News For You here.