Unsettling surgery statistic you might not know about

IT TURNS out it’s a lot easier to wake up while you are being operated on than you probably thought, with a staggering number of people able to recall parts of their surgeries.

WAKING up in the middle of an operation sounds like something out of a horror movie, but new research has revealed that it could happen a lot easier than you probably thought.

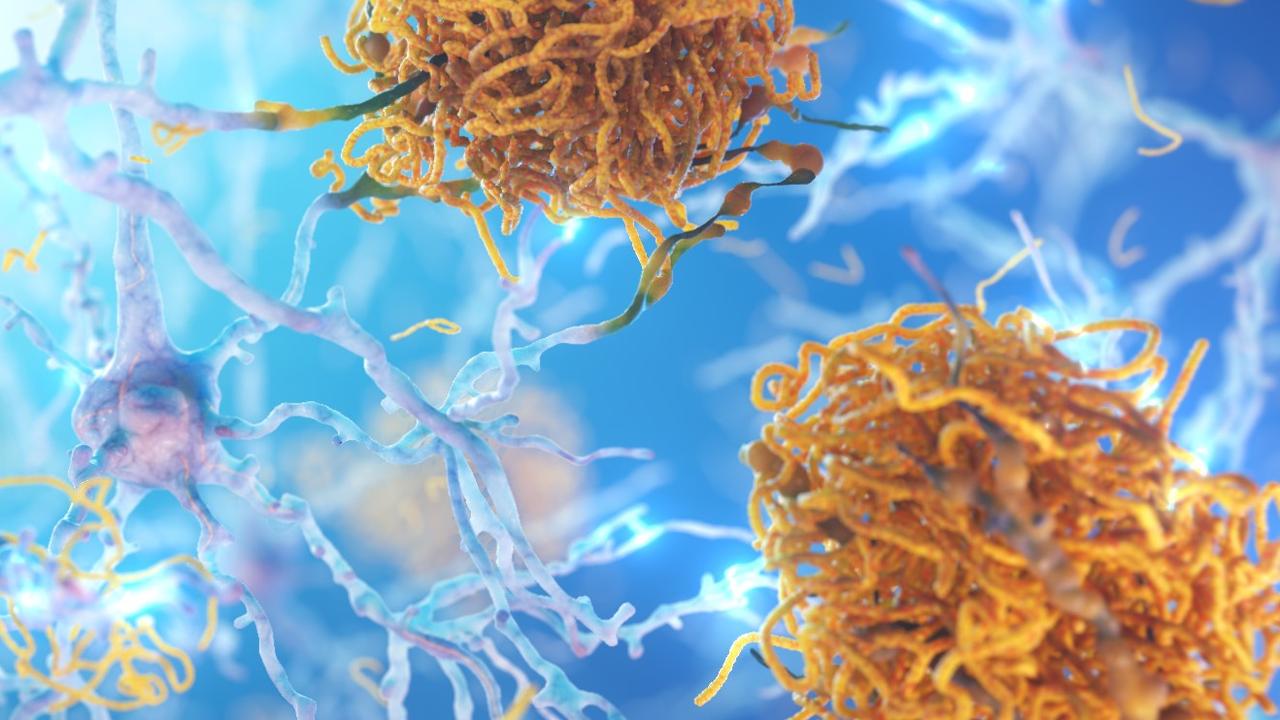

New research published in the journal Anesthesiology suggests that humans are not fully unconscious when under general anaesthetic. Instead, it is similar to a sleeping state.

A team of researchers at the University of Turku, Finland analysed changes to the brains of 47 healthy volunteers when under general aesthetic.

The patients were either given the sedative dexmedetomidine or the general anaesthetic propofol.

READ: Mum ‘butchered’ in surgery ordeal

It was discovered that something like a loud noise or being briefly shaken could be enough to bring people back to consciousness, with 42 per cent of participants able to be woken.

All of this took place after the patient reached either loss of responsiveness or loss of consciousness and while the drugs were still being administered.

“Nearly all participants reported dreamlike experiences that sometimes mixed with the reality,” study author and Professor of Psychology, Antti Revonsuo, said in a statement.

“The state of consciousness induced by anaesthetics can be similar to natural sleep. While sleeping, people dream and the brain observes the occurrences and stimuli in their environment subconsciously.”

Some of the participants were even able to recall parts of the operation, though their memories were hazy.

The participants were also played recordings of sentences that ended unexpectedly, to test how their brains would react to the unusual phrases.

“The night sky was filled with shimmering tomatoes,” was one of the lines used.

When a person is awake the unexpected word would usually cause a spike in brain waves as the mind tries to figure out the meaning of the word.

However, when the patients were under anaesthesia the brain was unable to differentiate between the normal and unusual words and there was a “significant” response to the whole sentence. This means that the brain became more alert trying to figure out what all of the words meant.

After the patients woke up though they could not remember the sentences that were played to them.

There were even more noticeable reactions when the participants were played unpleasant noises, with their brains reacting faster to those particular sounds after they woke up than others they hadn’t heard.

“In other words, the brain can process sounds and words even though the subject did not recall it afterwards,” Adjunct Professor of Pharmacology and Anaesthesiologist Harry Scheinin said.

Against common belief, anaesthesia does not require full loss of consciousness, as it is sufficient to just disconnect the patient from the environment.”