New frontier in cancer care: Turning blood into living drugs

IMMUNE therapy is the hottest trend in cancer care, creating “living drugs” that grow inside the body into an army that destroys tumours and “melt away” cancer.

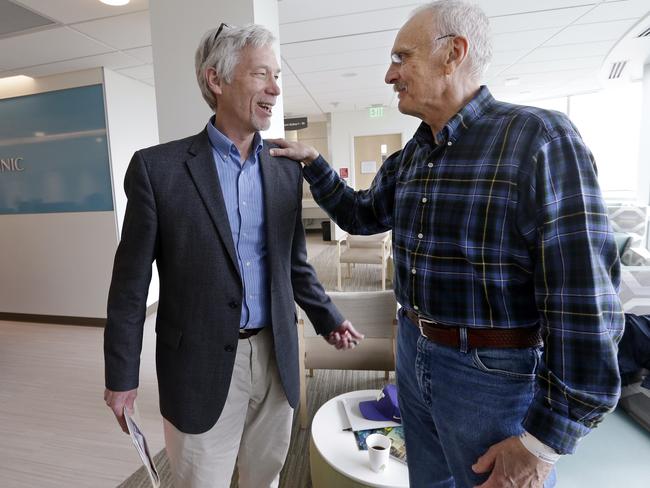

KEN Shefveland’s body was swollen with cancer, treatment after treatment failing until doctors gambled on a radical approach: They removed some of his immune cells, engineered them into cancer assassins and unleashed them into his bloodstream.

Immune therapy is the hottest trend in cancer care and this is its next frontier — creating “living drugs” that grow inside the body into an army that seek and destroy tumours.

Looking in the mirror, Shefveland saw “the cancer was just melting away.”

A month later doctors at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center couldn’t find any signs of lymphoma in the man’s body.

“Today I find out I’m in full remission — how wonderful is that?” said Shefveland with a wide grin, giving his physician a quick embrace. This experimental therapy marks an entirely new way to treat cancer — if scientists can make it work, safely. Early-stage studies are stirring hope as one-time infusions of supercharged immune cells help a remarkable number of patients with intractable leukaemia or lymphoma.

“It shows the unbelievable power of your immune system,” said Dr David Maloney, Fred Hutch’s medical director for cellular immunotherapy who treated Shefveland with a type called CAR-T cells.

“We’re talking, really, patients who have no other options, and we’re seeing tumours and leukaemia disappear over weeks,” added immunotherapy scientific director Dr Stanley Riddell. But, “there’s still lots to learn.”

T cells are key immune system soldiers. But cancer can be hard for them to spot, and can put the brakes on an immune attack. Today’s popular immunotherapy drugs called “checkpoint inhibitors” release one brake so nearby T cells can strike. The new cellular immunotherapy approach aims to be more potent: Give patients stronger T cells to begin with.

Currently available only in studies at major cancer centres, the first CAR-T cell therapies for a few blood cancers could hit the market later this year in the US.

The country’s Food and Drug Administration is evaluating one version developed by the University of Pennsylvania and licensed to Novartis, and another created by the National Cancer Institute and licensed to Kite Pharma.

CAR-T therapy “feels very much like it’s ready for prime time” for advanced blood cancers, said Dr Nick Haining of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, who isn’t involved in the development.

Now scientists are tackling a tougher next step, what Haining calls “the acid test": Making T cells target far more common cancers — solid tumours like lung, breast or brain cancer.

Cancer kills about 600,000 Americans a year, including nearly 45,000 from leukaemia and lymphoma. In Australia, cancer is estimated to the cause of more than 47,000 deaths in 2017, according to Cancer Australia statistics.

“There’s a desperate need,” said NCI immunotherapy pioneer Dr Steven Rosenberg, pointing to queries from hundreds of patients for studies that accept only a few. But for all the excitement, there are formidable challenges.

Scientists still are unravelling why these living cancer drugs work for some people and not others.

Doctors must learn to manage potentially life-threatening side effects from an overstimulated immune system. Also concerning is a small number of deaths from brain swelling, an unexplained complication that forced another company, Juno Therapeutics, to halt development of one CAR-T in its pipeline; Kite recently reported a death, too.

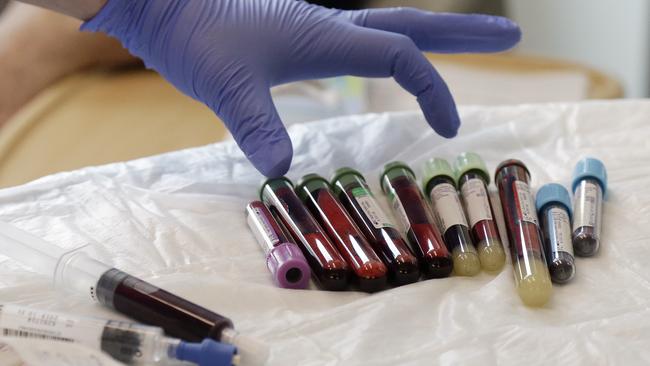

And, made from scratch for every patient using their own blood, this is one of the most customised therapies ever and could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“It’s a Model A Ford and we need a Lamborghini,” said CAR-T researcher Dr Renier Brentjens of New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, which, like Hutch, has a partnership with Juno.

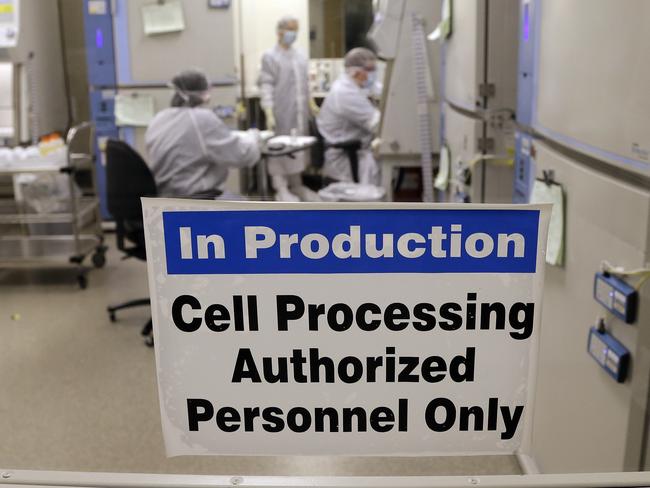

In Seattle, Fred Hutch offered a behind-the-scenes peek at research underway to tackle those challenges. At a recently opened immunotherapy clinic, scientists are taking newly designed T cells from the lab to the patient and back again to tease out what works best.

“We can essentially make a cell do things it wasn’t programmed to do naturally,” explained immunology chief Dr Philip Greenberg.

“Your imagination can run wild with how you can engineer cells to function better.”