Emerging AI-powered tech holds the promise of saving thousands of lives

IT’S one of the biggest killers in Australia which can easily stay hidden but new technology could soon save thousands of lives.

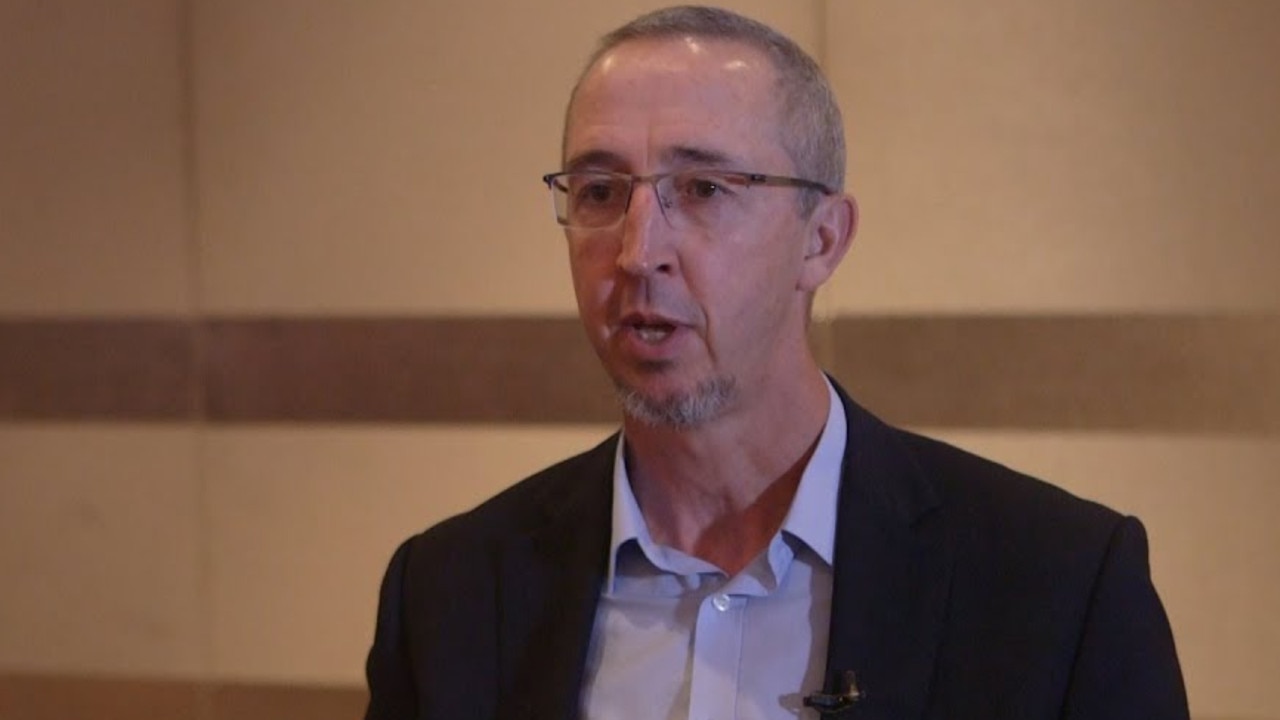

WHEN mathematician Dr Ralph Highnam was studying at Oxford University in the early 1990s, he was very interested in the emerging field of artificial intelligence.

But unsure where to focus his research, he had a conversation with a professor the same day the professor’s mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer and it took his interest down an unexpected path.

“Most of the AI back when I started was based around mobile robots and making vehicles move around autonomously in factories. That frankly wasn’t very interesting to me,” he told news.com.au.

As part of his PhD he began to pioneer a way to use computer software to detect and measure breast density in screening images. At the time, breast cancer screening was far from perfect and he thought artificial intelligence could revolutionise it.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in Australian women, aside from non-melanoma skin cancer and is the second largest cause of cancer death among Australian women. Dr Highnam believes more powerful tools to analyse screening images can help prevent many of these deaths.

He is now the CEO of Volpara Health Technologies, a New Zealand based company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange that sells breast cancer screening software which it claims can more effectively indicate cancer in breasts with greater density, lifting the accuracy of diagnoses.

“We tried to commercialise the work from Oxford but we realised the market wasn’t ready,” Dr Highnam said. “The clinical world takes a long time to change. At the time it wasn’t totally accepted that breast density was a risk factor in cancer.”

But nearly two decades later, when the science became more widely embraced, he and his team of fellow researchers returned to the work and set about building technology that could provide an automated measurement of breast density.

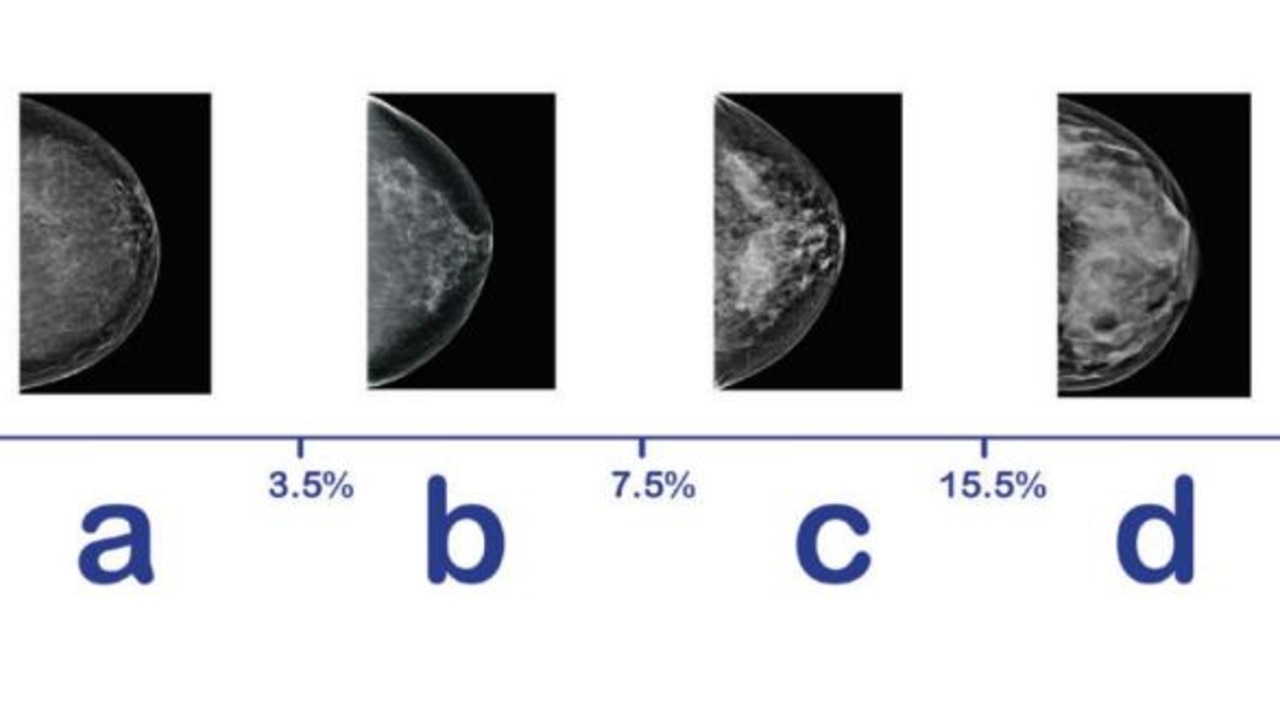

The problem, as the American College of Radiology put it as recently as January 2013, it that “the assessment of breast density is not reliably reproducible”.

When you look at a mammogram, the white on the breast X-ray is what doctors call dense tissue. But cancer, when it forms, is also white.

“Breast density hides cancers,” Dr Highnam said. “But not only that, women with dense breasts are four to six times more likely to develop cancer in the first place.”

Fatty tissue appears darker on X-ray imaging so women with fatty breasts who develop cancer will have it detected about 98 per cent of the time.

“If you’ve got extremely dense breasts, that goes down towards 50 or 60 per cent,” Dr Highnam said.

When not analysed by software or computational methods, it would be done visually by doctors which can prove troublingly subjective.

The software Volpara develops gives patient readings of their breast volume and the cubic centimetres of dense tissue, which can suggest the need for further testing like an MRI to detect anything dangerous.

“You can’t generate those kinds of numbers by eye,” Dr Highnam said.

However, when it comes to screening for breast cancer, there is still some debate about how useful it can be amid the potential to generate false positives, causing unnecessary stress.

A recent review of BreastScreen Australia estimated that the program reduces breast cancer mortality by between 21 and 28 per cent. While this is significant, mammography can also lead to overdiagnosis, the organisation says.

“There’s certainly a level of debate about over diagnosis … (But) there’s ways to optimise screening,” Dr Highnam said.

TAKING ON GOOGLE

Volpara certainly isn’t the only one toiling in this general field. In November 2017, the Cancer Research UK Imperial Centre and Google’s DeepMind Health announced that a consortium of top AI researchers and health care professionals would be put to the task of using Google’s AI tech to improve the reading and assessment of mammograms.

There is a “huge amount” on interest in this area of computer detection, Dr Highnam said.

“A lot of those companies take a pure AI approach to it, i.e. ‘just give us all the data and we’re gonna run computer algorithms and produce results’,” he said.

“Whereas right from my Ph.D onwards it has become very clear that the way to have successful application of AI is not just to treat breast images like car images. You need to understand how those breast images are formed, understand breast physiology, understand breast tissue, understand cancer, understand the whole domain of breast cancer before you start applying AI.”

In short, a deep medical understanding — on a molecular level — is required to underpin the algorithms being built.

Volpara is a growing company and is still seeking regulatory approval for some of its software products in various markets.

The company is looking to expand into the United States, Europe and the Asia Pacific and raised $20 million earlier this year to grow its force.

Facilities in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth are using the company’s breast density software, and some are using new cloud based tools the company has developed.

“We’re starting to create one of the world’s biggest data sets of breast images that we’re allowed to use for product development purposes,” Dr Highnam said.

This month is Breast Cancer Awareness Month and as doctors and researchers from around the world gather, it’s developments like this — the growing level of rich data sets and the application of AI — that has them excited about taking on one of the biggest killers of Australian women.