Early results from NASA’s identical twin study show the stress of life in space

IT’S a forgone conclusion that humankind will leave Earth in a bid to colonise space, but will our bodies be able to cope?

IT’S seems like a forgone conclusion that humankind will leave Earth and colonise space, but there is still so much we don’t know about the impact extraterrestrial living will have on the human body.

But thanks to a pair of identical twin brother astronauts at NASA, we are starting to get a much better idea. And the early signs don’t look particularly promising.

NASA astronaut Scott Kelly spent close to a full year in space, aboard the international space station, before returning in March 2016.

His extended stay in orbit has given scientists a much needed insight into the effects long term zero-gravity has on the human body.

Any legitimate science experiment requires a control sample, and fortunately for the American space agency, Mr Kelly just happens to have an identical twin brother, Mark Kelly, to perform that role.

Measurements taken before, during and after Scott Kelly’s mission and compared to his Earth-dwelling brother reveal changes in gene expression, DNA methylation and other biological markers, according to the preliminary results of the study reported in the journal Nature.

The comprehensive testing includes a range of physical testing from measuring the microbiomes in their guts to the lengths of their chromosomes.

The data is very fresh but “almost everyone is reporting that we see differences,” said Christopher Mason, a geneticist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. He and other researchers reported the early results at a Texas meeting of scientists working in NASA’s Human Research Program.

Last year, NASA’s Human Research Program chief scientist John Charles referred to the testing as “the most complex biomedical investigation ever done on the space station”.

The challenge now is to untangle how many of the observed changes are specific to the physical demands of spaceflight, and how many might be simply due to natural variations, scientists said.

The sample size is too small to be extrapolated to the broader population but when it’s all said and done it will provide researchers with crucial data into the impact of life in space.

The testing will help show how a zero gravity environment and the resulting fluid redistribution can potentially harm eyesight.

With the absence of gravity, bodily fluids are free to move around the body far more freely and it’s believed an increase in fluids around the brain causes greater pressure to be placed on the optic nerve, deforming astronauts eyeballs. Such a process is thought to cause instances of short sightedness in returning astronauts.

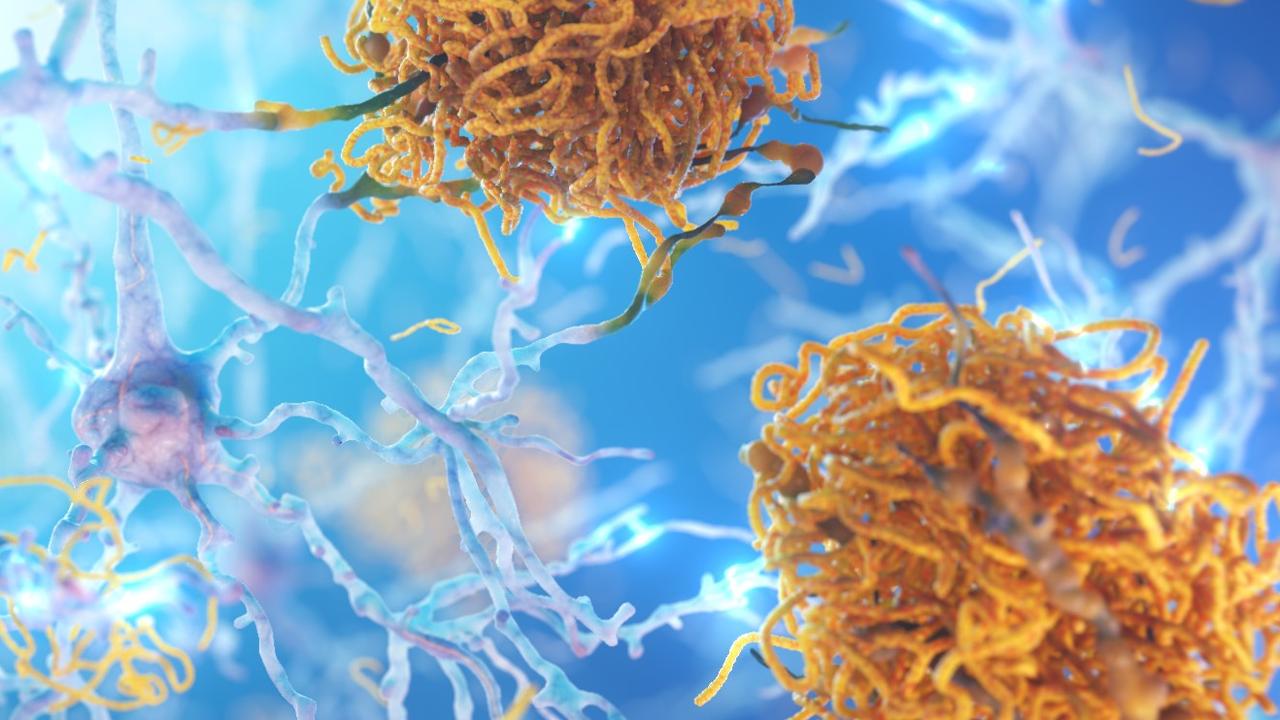

The other major thing scientists are hoping to gain greater understanding of is the impact that an additional level of radiation has on the structure of human DNA.

The cosmic universe has UV radiation hundreds of times greater than the Earth’s surface, as well as being filled with potentially dangerous cosmic rays.

Exactly how these forces affect our DNA is not entirely understood.

It’s possible that the stress of spaceflight speeds up the naturally occurring process in which telomeres shorten. Temoeres are the protective caps at the end of each strand of our DNA that protect chromosomes, and if space travel does indeed impact the shortening process in such a way, it would amount to a speeding up of an astronaut’s biological clock.