Controversial scientist resumes gene editing work to cure Alzheimer’s, muscular dystrophy

A scientist who was jailed for manipulating the DNA of babies has made a huge claim about some of the nastiest diseases facing the world.

A Chinese scientist who was jailed for manipulating the DNA of three babies is back on the job.

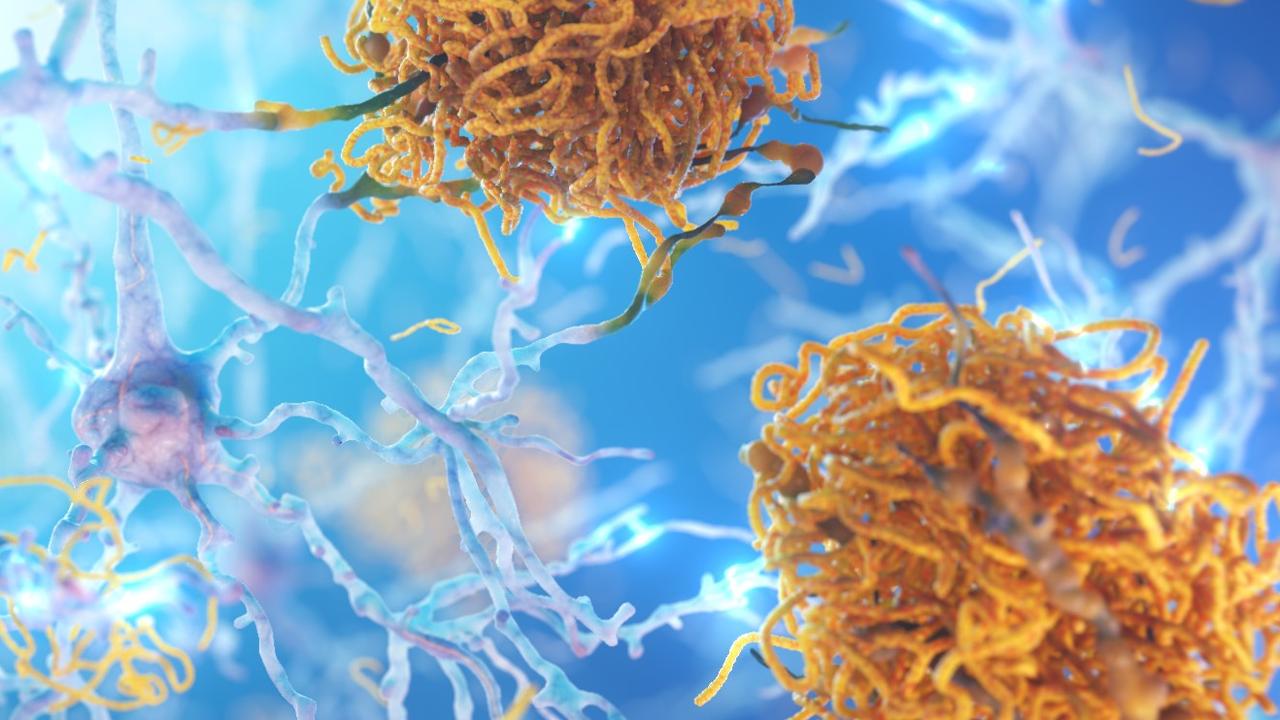

This time, he wants to cure the world of Alzheimer’s and muscular dystrophy – once the world accepts “that embryo gene editing is a good thing”.

The global scientific community was shocked in 2018 when it went public that biophysicist He Jiankui had “edited” the genes of three babies (two of which were twins) to give them resistance to HIV.

These were the first gene-edited human babies ever born.

The Chinese research team had targeted a gene tagged CCR5, which the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) revealed was a “multipurpose” gene that also influenced intelligence.

“The answer is likely yes, it did affect their brains,” University of California neurobiologist Professor Alcino Silva told the MIT Review at the time.

“The simplest interpretation is that those mutations will probably have an impact on cognitive function in the twins,” Prof Silva said.

After the expose, Mr He was jailed by the Chinese Government for three years and fined $750,000. That prison sentence for breaching medical regulations ended in 2022.

Now, the genetic scientist has spoken with MIT about his plans for the future.

“There will be no more gene-edited babies. There will be no more pregnancies,” he told an MIT online discussion.

But he said he has been approached by “Silicon Valley” investors to establish a new company to advance his controversial work.

Incomplete experiment

Mr He has kept in touch with the families involved in his original divisive experiment, revealing he is giving one, now a single mother, “some financial support”.

“Lulu, Nana, and the third gene-edited baby – they were healthy and are living a normal, peaceful, undisturbed life,” he said.

“They are as happy as any other people, any other children in kindergarten. I have maintained a constant connection with their parents.”

The biophysicist said the initial plan had been to expose umbilical cord blood from the newborn babies to the HIV virus to see if it resisted infection.

“This experiment never happened because, when the news broke out, there has been no way to do any experiment since then,” Mr He told the MIT panel.

But he revealed he had maintained regular contact with the third baby, whose parents had divorced.

The child’s single-parent mother had been struggling with cost-of-living pressures.

“So in the last two years, I’m providing some financial support,” Mr He said.

“But I’m not sure it’s the right thing to do or whether it’s ethical.”

New purpose

Mr He said he “decided to do Alzheimer’s disease because my mother has Alzheimer’s.”

“So I’m going to have Alzheimer’s too, and maybe my daughter and my granddaughter. So I want to do something to change it,” he said.

The researcher said he had restarted his genetic manipulation research with funding from unnamed Chinese and US companies.

His current work, conducted in a private laboratory in Sanya City, Hainan Province, includes gene editing to tackle various inherited conditions, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

For the moment, his work is limited to adding modified genes to a living person’s somatic (non-reproductive) cells, Mr He told MIT.

But he wants to work on human embryos once again.

“So my goal is we’re going to test the embryo gene editing in mice and monkeys and in human non-viable embryos,” he said.

“We’re going to stop at human non-viable embryos.”

The purpose is to prove whether or not the genetic precursors for Alzheimer’s can be prevented from being passed down to the next generation.

And Mr He insisted his research is based on natural genetic traits already identified in humans, particularly among Scandinavian populations.

“Why don’t we just make some modifications so our next generation may also have this protective allele (gene variant) so they have a low risk or maybe are free of Alzheimer’s,” me He said.

“That’s my goal.”

‘A good thing’

But Mr He refused to answer questions regarding support from the Chinese Government. Nor would he identify what companies were offering to fund his ongoing work.

“I believe society will eventually accept that embryo gene editing is a good thing because it improves human health,” Mr He told the MIT panel.

“So I’m waiting for society to accept that.”

He believes the basic research will be finished within two years. But the next phase – human trials – will be somebody else’s problem.

Whatever the future holds, Mr He said he was “not interested” in letting natural evolution take its course.

“Evolution takes thousands of years. I only care about the people surrounding me – my family and also the patients who would come to find me,” he said.

“What I want to do is help those people, help people in this living world. I’m not interested in evolution.”

He insisted he does not regret tinkering with the genetic makeup of the three children who were the subjects of his original experiments.

“The only regret I have is to my family, my wife and my two daughters. In the last few years, they are living in a very difficult situation,” he said.

“I won’t let that happen again.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel