Treasure hunter Tommy Thompson on the run after court dispute challenges his claim to wreck’s gold

HE found tons of sunken gold worth millions of dollars. But Tommy Thompson’s lust for treasure consumed him - and now no one knows where he is.

ONE of the last times anyone ever saw Tommy Thompson, he was walking on the pool deck of a Florida mansion wearing nothing but eye glasses, leather shoes, black socks and underwear, his brown hair growing wild.

It was a far cry from the conquering hero who, almost two decades before, docked a ship in Norfolk, Virginia, loaded with what’s been described as the greatest lost treasure in American history — thousands of pounds of gold that sat on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean for 131 years after the ship carrying it sank during a hurricane.

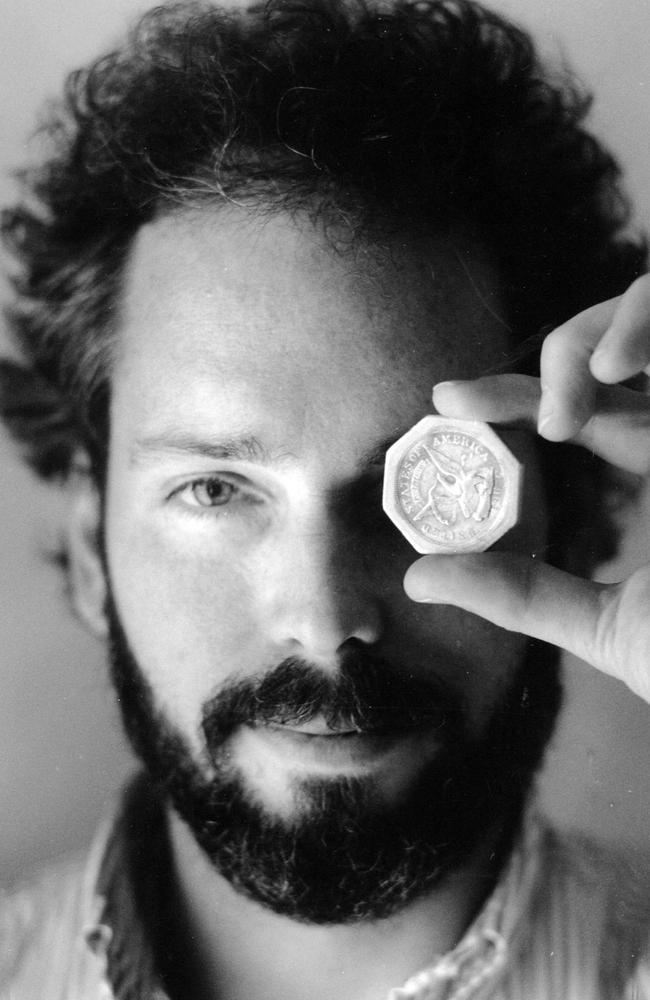

On that day in 1989, Thompson couldn’t contain a gap-toothed grin as a marching band played My Way and hundreds cheered his achievement. It was, indeed, monumental: the result of years of preparation, innovation, dogged single-mindedness and a belief that Thompson could not only find the gold, but also use the experience to track down other sunken treasure.

RELATED: SS Central America releases riches of gold, silver

“We hope to be rich,” he said then. But his victory was short-lived.

Also in Norfolk that day were insurers laying claim to Thompson’s gold. He would eventually win the legal nightmare that ensued, but those closest to him believe it was the beginning of the end. Soon another court fight began with investors who funded his dream but never saw a penny back, and Thompson grew increasingly private, transforming into a Howard Hughes-like recluse.

Still, what came next was a surprise to all. Tommy Thompson disappeared.

TREASURE TROVE

These days, off the South Carolina coast, a new expedition is underway to recover more treasure from the “Ship of Gold,” the sunken SS Central America. Inside the mess hall of the barge making the voyage hangs a “Wanted” poster of the man who first found the ship.

The US Marshals Service wanted the poster of Thompson displayed so the crew would recognise him in case he shows up, lured out of the shadows by the galling idea that someone else is collecting the gold he unearthed.

“They’ve awakened the sleeping beast,” Marshals agent Mark Stroh says of the wave of publicity that has introduced the tale of the treasure and its fugitive discoverer to a new generation.

Stroh and fellow agent Brad Fleming remain captivated by the man they’ve pursued these last two years, since Thompson skipped a court date to explain what’s become of the riches.

ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM: Search for ancient computer begins

They’ve done meticulous research on Thompson to better understand their target, splashed his face on electronic billboards and run down hundreds of tips from the public — from the guy who thought he might have shared an elevator with Thompson at a Florida casino to a report that the name “Tommy” was signed on a memorial website for a dead friend of the treasure hunter.

Nothing has panned out.

“I think he had calculated it, whatever you want to call it, an escape plan, a contingency plan to be gone,” says Fleming. “I think he’s had that for a long time.”

As the agents share Thompson’s story, their mix of bewilderment and something akin to admiration for the treasure hunter is clear. Stroh likens Thompson to some of the greatest men in history. Christopher Columbus. Thomas Edison.

“He set out to find the Central America in the middle of a whole vast expanse of nothing and found it, and did it with relative ease,” Stroh says, “like he was trying to find a set of car keys he misplaced in his house, but the house is hundreds of miles of ocean.”

A person like that, the agent says, is not going to be pulled over for running a stop sign.

BOUNTY FROM THE DEPTHS

As the hunt for Thompson and the court fights go on, so does the new expedition to the Central America.

Since April, Florida-based odyssey Marine Exploration has brought up millions of dollars in gold and silver bars and coins from the shipwreck. That work will continue indefinitely, an odyssey spokeswoman says.

The operation is being directed by Ira Kane, a court-appointed receiver over two of Thompson’s companies. Kane will get more than 50 per cent of the recovered treasure, to be disbursed in part to Thompson’s investors.

“Remember, only 5 per cent of this ship was excavated,” Kane told The Associated Press in March.

As to where Thompson, now 62, and his assistant might be, theories abound.

Szolosi, the crew members’ attorney, suspects he’s holed up in a safe house somewhere. Kinder, the author, says nothing in his time with Thompson gives him any insight.

“I don’t know what it would entail to hide like that. Get your teeth fixed? Buy a blond wig? Do you fake a passport and go to Bolivia or something? I have no idea.”

Agent Fleming believes Thompson is likely still stateside, but because of his sailing experience, “We definitely never rule out the fact that he may be abroad or at sea.”

If caught, Thompson would be asked to account for the missing coins and explain where proceeds from the treasure’s sale and other deals have gone. If he refuses, he could be jailed and face hefty fines.

Thompson’s family — he has three grown children, three siblings and a 93-year-old mother — just hope he is enjoying being free, says Milt Butterworth, his brother-in-law.

“The sadness for me is that I don’t have him and the family doesn’t have him, but the happiness for me is that he doesn’t have to worry about this anymore.”

As for Kirk, Thompson’s friend, the treasure hunter remains an American hero, “like the Wright brothers,” he says. “There’s no telling what he would have done by now.”

The tragedy, as he sees it, is that Thompson’s dream became his doom.

“Tommy used the word, what’s the word?” Kirk says. “Plague of the gold.”

THOMPSON’S TALE

As a child in his small hometown of Defiance, Ohio, Thompson displayed an intelligence that was as remarkable as his sometimes maddening refusal to do anything the normal way.

His mother, Phyllis, describes how her son took things apart and put them back together, just to understand how they worked. When he was eight, Thompson almost got his parents in trouble with the phone company for having two lines without paying for both. Turns out, the boy had split the wire, connected it to a jewellery box and built himself a telephone, according to author Gary Kinder’s Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea.

Kinder says his book isn’t really about a hunt for a shipwreck and its riches.

“It’s about a guy’s brain and how it works,” he says of Thompson. “There’s something special about people like Tommy. It’s someone … who will not be put off by people telling him, ‘This cannot be done.’ … It requires a lot of faith in oneself, a lot of confidence, and slowly bringing people to share their vision.”

That talent is part of the reason Ohio businessmen got on board when Thompson set his sights on finding the Central America around 1983.

In one of the worst shipping disasters in American history, the boat sank about 320 kilometres off the South Carolina coast in September 1857; 425 people drowned and thousands of kilos of California gold were lost, contributing to an economic panic.

When Thompson, then 31, began approaching potential investors, he was an oceanic engineer at Battelle Memorial Institute, an international technology development group. In Columbus, where it’s headquartered, Battelle’s name is as synonymous with innovation and genius as MIT or Google.

Thompson also had the backing of the dean of the mechanical engineering school at his alma mater, Ohio State University.

“He’s a very bright guy with lots of ideas, very creative and wild thinking, and just full of energy,” says the dean, Don Glower, now 87 and retired.

Glower and the school’s head of fundraising arranged for Thompson to meet a group of wealthy Columbus-area businessmen who could finance Thompson’s plans, with convincing.

“Tom was a pretty good salesman,” says Glower, who was at that first meeting. “He had me excited, but I didn’t have any money … I thought it was probably a pie-in-the-sky type of thing. But I said, ‘I think he’s a very bright guy, and if anybody could find it, it’s him.’”

And find it he did. It took an initial $US12.7 million from investors, a team of experts, competition from other treasure hunters, and the development of technology that allowed items to be retrieved unscathed from the deep ocean.

Thompson described the moment, on October 1, 1988, when he first gazed upon the gold.

“None of us ever thought that it would be so otherworldly in its splendour,” he wrote in America’s Lost Treasure, a companion to Kinder’s book. “Part of our American heritage, this was history in the form of a national treasure. And we had found it.”

His joy faded fast. Thirty-nine insurance companies sued Thompson, claiming they had insured the gold in 1857. The treasure, they argued, belonged to them.

CONSUMED BY GOLD

For years, the court battle raged. In 1996, Thompson’s company was awarded 92 per cent of the treasure, and the rest was divided among some of the insurers.

Investors thought they’d finally see returns, too, but Thompson held them off, saying the gold had to be marketed just so. Finally in 2000, Thompson’s company sold 532 gold bars and thousands of coins to the California Gold Marketing Group for about $50 million.

But by 2005, Thompson’s 161 investors still hadn’t been paid. Two sued — a now-deceased investment firm president who put in some $250,000 and the Dispatch Printing Company, which publishes The Columbus Dispatch newspaper and had invested about $1 million. The following year, nine members of Thompson’s crew also sued him, saying they also had been promised some proceeds.

A new legal mess had begun. Thompson’s personal life had suffered, as well. His father died months after he found the gold. And his obsession with the treasure contributed to his divorce in 1991, friends and family say.

In 2006, Thompson went into seclusion, moving into a mansion called Gracewood in Vero Beach, Florida. He grew increasingly reclusive, and his behaviour turned bizarre.

Thompson refused to use his real name on his utility bills, telling realtor Vance Brinkerhoff that his life had been threatened and asking him, “How would you like to live like that?” Brinkerhoff recounted the exchange in a court deposition in the crew members’ lawsuit.

Brinkerhoff said Thompson paid his $3000 monthly rent in mouldy $100 bills. Because he didn’t want Brinkerhoff coming to the house, Thompson insisted on meeting elsewhere.

Once, when Brinkerhoff did go to the property, he found Thompson apparently living in a van outside.

“He shared with me that he contracted some kind of skin disease on some kind of a safari trip … and he was very sensitive to different kinds of materials,” Brinkerhoff said in court documents.

In another deposition, maintenance worker James Kennedy recounted once going to the house to ask Thompson about rent and seeing him on the pool deck wearing only socks, shoes and dirty underwear.

“His hair was all crazy,” Kennedy said. “After that, me and (a friend) referred to him as the crazy professor because it just fit.”

All the while, the legal battles slogged on.

Gil Kirk, who heads a Columbus real estate firm and is a former director of one of Thompson’s companies, says he put US$1.8 million into the treasure hunt. He hasn’t gotten any of that back, but he remains a supporter of Thompson and insists he never bilked anyone. Kirk said proceeds from the 2000 sale all went to legal fees and bank loans.

“He was a genius, and they’ve stolen his life,” Kirk says of those who sued.

Steven Tigges, attorney for the Dispatch company and the other investor-plaintiff, did not respond to requests for comment, nor did a number of the investors.

The crew members’ lawyer, Mike Szolosi, asserts that he’s seen records indicating Thompson took 500 gold restrike coins worth US$2 million and took potentially millions from his own company on top of his approved compensation.

“Presumably all of that is still somewhere with Tommy,” Szolosi says.

Attorney Rick Roble defended Thompson’s company from the 1980s until he withdrew from the case last month. He maintains there is no proof that Thompson stole any money or gold.

“If he did take money,” Roble says, “where is the evidence of that?”

It’s not clear exactly when Thompson disappeared. On August 13, 2012, he failed to appear at a court hearing, and a federal judge found him in contempt and issued an arrest warrant.

At the hearing, Thompson attorney Shawn Organ told the judge that his client was “at sea” and didn’t know he was supposed to be in court. An arrest warrant also was soon issued for Thompson’s assistant, Alison Anteiker, who also failed to appear in court and whom the Marshals agents believe is with Thompson.

Not long after Thompson vanished, Kennedy returned to the Florida mansion and found it in a shambles — cabinets falling off walls, rats running around.

Pre-paid disposable cellphones and bank wraps for $10,000 bills were scattered about, along with a bank statement in the name of Harvey Thompson showing a US$1 million balance, Kennedy said in court records. Harvey, according to friends, was Thompson’s nickname in college.

Also found was a book called How to Live Your Life Invisible. One marked page was titled: “Live your life on a cash-only basis.” Then Kennedy spotted a copy of Kinder’s Ship of Gold and looked Thompson up on the internet, discovering that he was a fugitive.

He called the Marshals Service.