The truth about Stonehenge: New survey reveals more secrets

IT’S ominous. Forbidding. Mystical. But everything we think we know about the ancient landmark Stonehenge may be wrong.

OMINOUS. Forbidding. Mystical. But, now, everything we think we know about the ancient landmark Stonehenge may be wrong.

New clues reveal it may have been a busy, bustling hive of activity.

Previously it was thought to be a temple of the dead, accessed once or twice a year by a solemn procession winding its way along the River Avon and Salisbury Plain from a woodhenge — a nearby “temple of life”.

Stonehenge was supposed to be a serene place. A magical place.

But it may not have always been so. And it certainly isn’t now (with the adjoining highway, carpark and visitor centre).

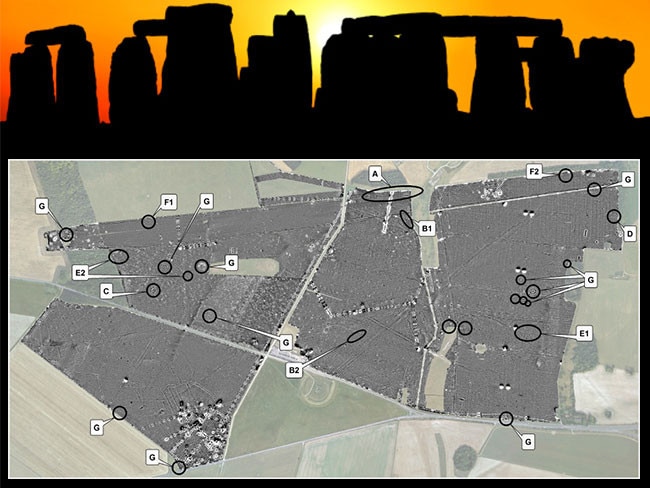

A recent extensive survey of the fields around the 4000-year-old iconic standing stones has uncovered 15 possible new Neolithic structures.

‘Possible’ because they haven’t been excavated yet.

The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project has built up a six-square kilometre geophysics survey of the historic site, using ground-penetrating radar and magnetometers to find out what lies beneath the grassy fields. The four-year project began in 2009.

What they found was a hive of other henges, pits, ditches and barrow-tombs, an article for the Smithsonian Institution reveals.

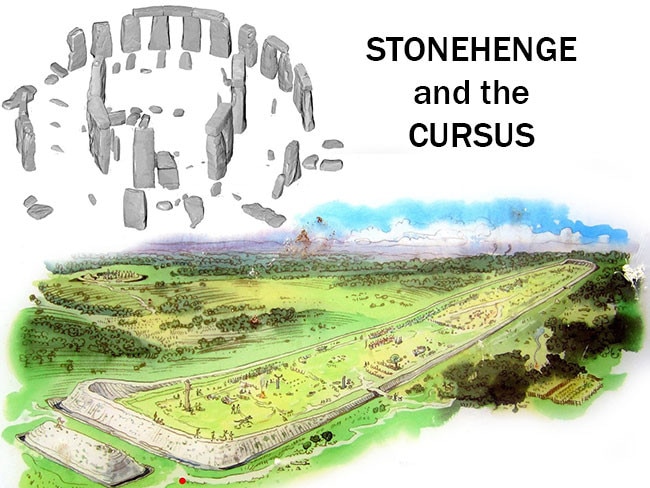

Among the most significant finds are two huge pits which have significant alignments with Stonehenge’s central Heel Stone for times such as the sunrise and sunset on the summer solstice. They also give relevance to the nearby Neolithic “Cursus”, a huge but poorly understood earthen mound which sits alongside the standing stones.

Ancient Stonehenge, it seems, was very much alive.

“There was sort of this idea that Stonehenge sat in the middle and around it was effectively an area where people were probably excluded, “a ring of the dead around a special area — to which few people might ever have been admitted” researcher Vince Gaffney told the Smithsonian.

But the evidence of such a high level of activity may change all that.

So we’re back to where we started.

We have no idea what Stonehenge is all about.

Archaeologists know people were buried there. They know the stones have important astronomical alignments — particularly for the summer solstice. They also know people were willing to travel hundreds of miles to visit the imposing standing stones.

Why? That’s another matter.

The more archaeologists discover, it seems the less we know about the purpose of Stonehenge.

But that’s not stopping anyone from trying.

Gaffney has his own ideas about what the new Stonehenge structures may mean.

It was a complex “processional”, he says — where priests and people followed a miles-long path, conducting theatric ceremonies and rites at each individual “station”.

But he’s not sure.

“Until you dig holes, you just don’t know what you’ve got,” Gaffney told the Smithsonian.

“This is among the most important landscapes, and probably the most studied landscape, in the world,” Gaffney says. “And the area has been absolutely transformed by this survey. Won’t be the same again.”