‘The time is now’: Aussie connection to ‘looted’ sculptures

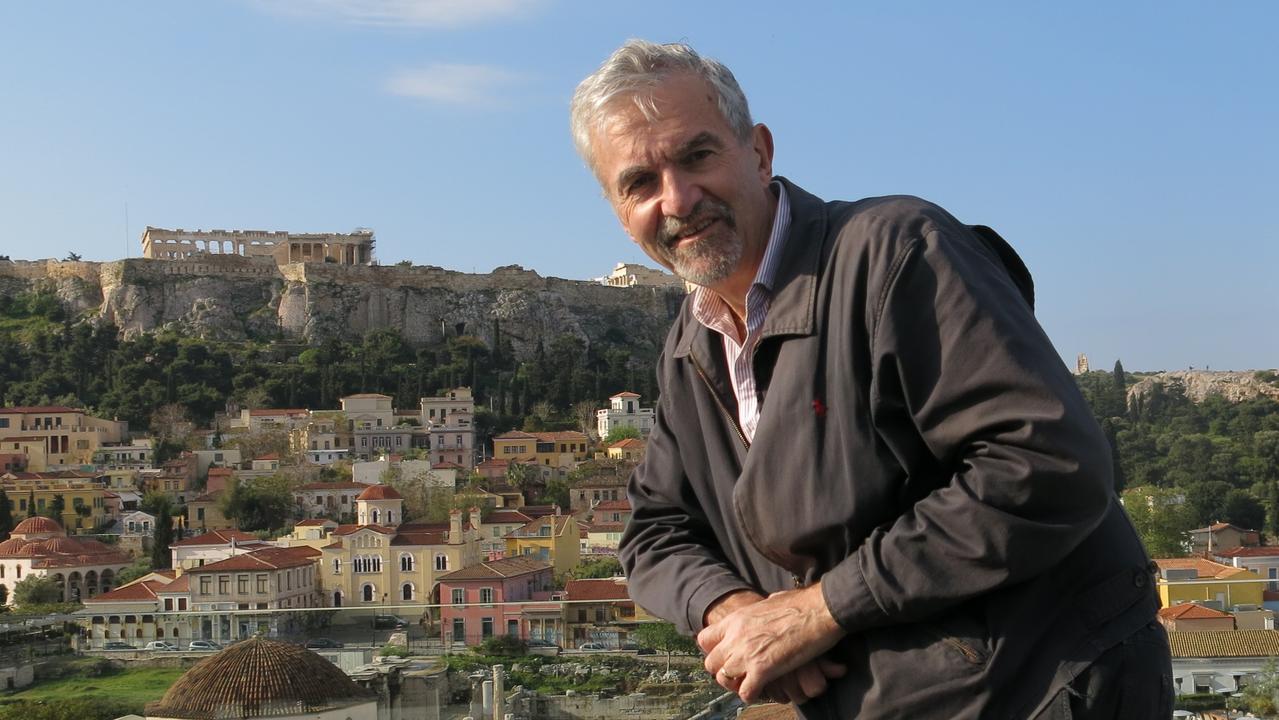

Many people have joined the fight to return the iconic Parthenon Marbles to their rightful home in Athens – but none are more passionate than my dad.

The Parthenon Marbles need to be returned to Greece.

I’m not sure why there’s even a debate about it. I’m not sure why people, like my dad George Vardas, have spent years and years creating awareness and fighting for something that shouldn’t even be a fight.

It’s a case that’s gained the attention of renowned human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson, who outright agrees they were stolen. Fellow human rights lawyer Amal Clooney and her husband actor George Clooney have also been involved in supporting the cause.

“The time is now”, my father says, the Co-Vice President of the Australian Parthenon Association, who works alongside former ABC chairman David Hill, who is the chairman of the committee.

The group is lobbying for the return and reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, to the Acropolis Museum in Athens. They’re active on social media, they publish articles and are featured in national and international media, offer advice to the Greek government whom which they have a close working relationship with, and importantly, educate the public about the issue and importance of restoring significant looted culture artefacts to their place of origin.

It’s a debate that’s been ongoing for years. Now, the campaign for their return is back in limelight, as the Australian Parthenon Association is calling for Australian restitution supporters to join the cause.

APS is launching its restitution campaign on the heels of UNESCO’s recent historical and unanimous decision in favour of the Sculptures’ return to Greece, with a seminar, “All you ever wanted to know about the Parthenon Sculptures” which will be held during the Greek Festival of Sydney, this Sunday at the University of New South Wales.

Renowned Australian businessman, author and Chairman of APS, David Hill, will be presenting the case against the British Museum which has claimed the Parthenon Sculptures as its own for the past 200 years.

“As global calls for restitution of artefacts of significant cultural heritage mount, we’re urging all Australians to seize the opportunity to learn about The Parthenon Sculptures’ history and to join the fight for their restitution. We now live in a world where we’re increasingly accepting historical truths and collectively moving toward righting past wrongs,” Mr Hill said.

So what’s the issue?

The Parthenon sits at the top of the Acropolis, a fortress in Athens which is two and a half thousand years old. It’s one of the most iconic building on earth and in its glory featured incredible sculptures of gods, goddesses, elaborate and intricate scenes – all made out of marble.

But when the Greeks were under Ottoman Occupation, Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire abused his diplomatic position and allegedly bribed local officials to allow his workers to remove approximately one half of the existing sculptural decoration on the Parthenon. He shipped them to London, and after an enquiry was conducted in the British parliament, the British government purchased his collection, and transferred the sculptures to the British Museum in 1816, in which they have been ever since.

The Greek argument

Supporters of the cause have argued that the fragmented parts of the sculptures in London should be reunited with the surviving sculptures in Athens in the new museum, within proximity of the Parthenon and in line of sight of the sacred rock, the Acropolis.

“We’re talking about a mutilated monument being reunited so that all of the known surviving sculptures can be appreciated in their proper context”, Vardas says.

Greece has made renewed calls for dialogues with the British government and the British Museum over the years, but to no avail.

The British argument

The British contend the sculptures were legally obtained by Elgin and in effect now tell a different story in London where they have been for more than 220 years. It is further argued that the British Museum is a universal museum, and the sculptures are an important part of their entire collection. They are prohibited by the British Museum Act by disposing of any part of their collection. The British Government has stated repeatedly that it has no intention of changing that law and that it is a matter for the trustees. “It’s a classic cultural catch-22”, says Vardas.

I’ve been to the British Museum. I’ve stood in the gallery in which the sculptures sit. There’s nothing inspiring about how they’ve been presented at all, and I could wax lyrical about how truly glorious they would be if they were returned to Athens, to the new Acropolis Museum built specifically for them, but sits empty, and waiting.

And to my dad’s credit, he doesn’t stop short of just the Marbles – he’s passionate about other projects such the Benin Bronzes and closer to home, the Gweagal Shield taken by Captain Cook. His work and passion is honestly inspiring, and I’m constantly left in awe. Needless to say I’m one very proud daughter. He’s right – the time is now. It’s time for the Parthenon Sculptures to go home.

Australians wishing to join the cause for restitution can register for the “All you ever wanted to know about the return of the Parthenon Sculptures” here.