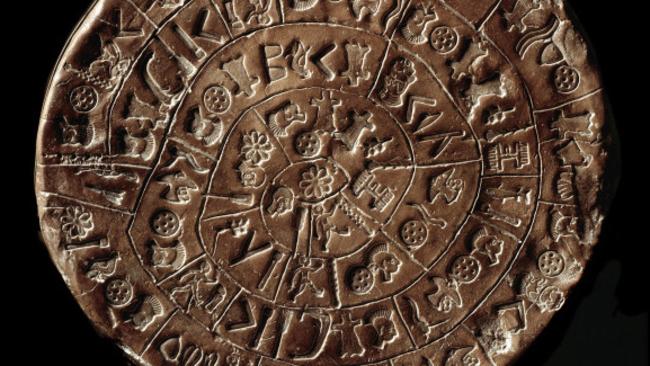

Sounds of an ancient world recovered from enigmatic Minoan Phaistos Disk

IT’S one of history’s greatest mysteries: A 4000-year-old clay disc covered in spirals of enigmatic writing. Now scientists think they have extracted key words.

FOR more than a century, scientists have been puzzling over this mysterious 4000-year-old inscribed disk discovered on Crete. Now it’s been decoded. Well, three words have.

While we know what the remaining words may have sounded like, we don’t know what they mean.

The 16cm wide Phaistos Disk’s unusual spiral cuneiform (picture) writing is both beautiful and enigmatic.

Linguistic researcher Dr Gareth Owens quipped during a presentation to a recent TED talk that it is the “first Minoan CD-ROM”. Now, it’s given up the sounds of a long-dead language.

The problem is: Nobody understands what they say.

Except, perhaps, for three.

Dr Owens and Professor John Coleman of Oxford University have spent six years attempting to unravel the fired clay disks’ mysteries.

Inscribed on both sides, the disk is divided into 241 segments with phrases made up of combinations of 45 different images.

Through extensively cross-referencing later hieroglyphics such as the Minoan Linear A and Mycenean Linear B, the scientists have now been able to build a phonetic translation of the script.

Only three words are recognisable.

IQE: Mother goddess

IQEKURJA: Pregnant mother goddess

IQEPAJE: Shining mother goddess

While these are just three of the phrases contained on the disk, it goes a long way to suggesting the clay tablet was a holy object containing a prayer for an ancient Minoan fertility goddess.

The disk was discovered in 1908 at the palace of Phaistos, Crete, and is believed to date from roughly 1700BC.

Dr Owens says there is little hope of cracking the code further.

“It goes without saying that the language of the Disk is unknown,” Dr Owens writes on the Technological Educational Institute of Crete (TEI) website, “and thus the text remains beyond our reach. Nevertheless, this has not deterred many potential decipherers from offering their own interpretations. Indeed, more has been written about this Cretan inscription than about any other ...”

The very fact it is a prayer also makes it a difficult code to crack.

The decipherment of Linear B in 1952 was largely because much of the discovered examples of the script were part of a standardised tax archive, listing people and products offered as sacrifices at temples.