‘Profoundly significant’: 3000yo drawing’s bombshell religious claim

It looks like a crude scribble on an old pot – but this 3000-year-old picture calls into question one of the most fundamental “truths” of Christianity.

On the surface, it looks like a crude scribble on an old broken pot. But this 3000-year-old picture challenges the origins of God.

Kuntillet Ajrud is a mysterious place. It’s a dusty, abandoned mound of rubble sitting atop a desert spur in Sinai, Egypt, near modern-day Israel.

Excavations in 1975 uncovered a fortified building of two main rooms. Both rooms had remnants of painted walls. Each room held one large, decorated water jar. And scattered here and there were potsherds.

Some 3000 years ago, it was a thriving outpost.

Precisely what it was for remains uncertain.

Was it a fort? A trading post? An inn? A religious school?

It took archaeologists four decades to publish a report on the excavation.

That’s because the site has proven so hard to define. And then there are the profoundly significant religious implications of the inscriptions and images found there.

THE WRITING ON THE JARS

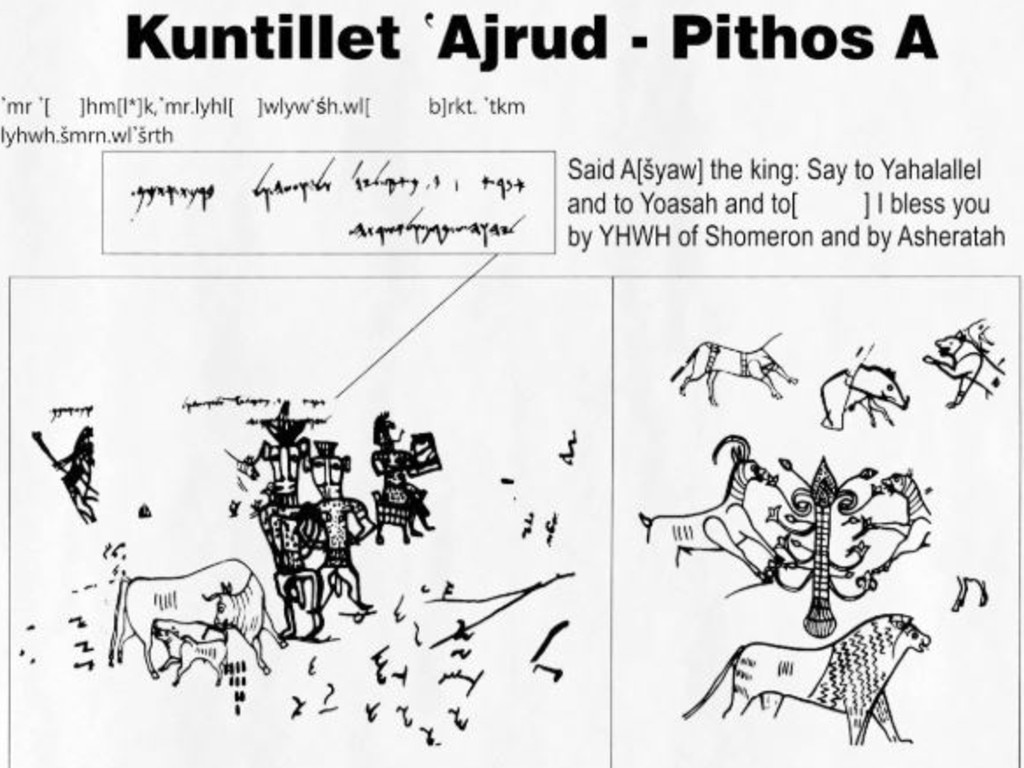

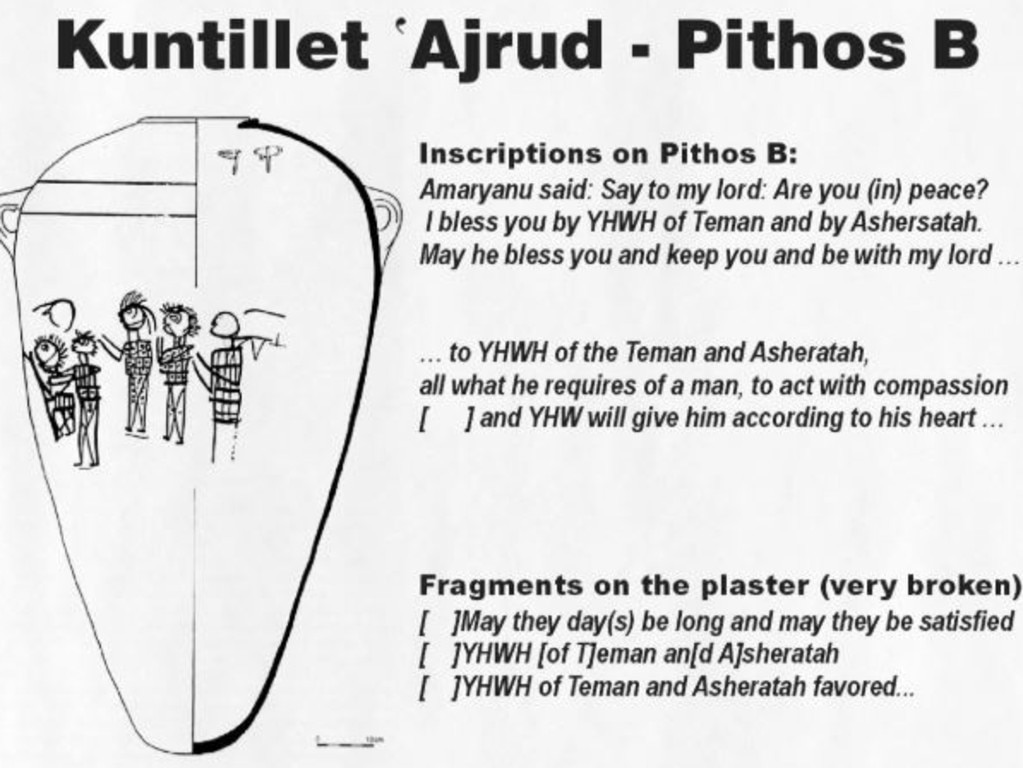

While Kuntillet Ajrud produced many paintings and inscriptions, those on the remains of two large jars stand out.

Of a type known as pithoi, they appear to have been in use for a considerable time.

They were undoubtedly considered valuable.

They were made of clay found near Jerusalem. They would have been carefully lugged a great distance to their final resting place. Once in position, they seem to have been in almost continuous use for some 25 years.

On them were painted crude scenes of cattle, lions, ibexes, trees, praying humans and deities.

Archaeologists note that different elements appear to have been painted at different times by various artists. But one thing is consistent: the style is incredibly rare, with little sign of the dominant Egyptian artistic forms of the time.

It is Phoenician. And the writing is in Ancient Hebrew and Phoenician.

RELATED: Is this the face of Mary Magdalene?

RELATED: Curse of the Templars lives on

RELATED: The great Christmas tree heresy

A detailed report on the excavation was published in 2012 by Tel Aviv University archaeologist Ze’ev Meshel.

The arguing hasn’t stopped since.

Several inscriptions continue to be the source of fascination and controversy.

One reads: “I have blessed you by Yahweh of Samaria and (his) Ashera.”

Another says: “Yahweh and Teman and his Ashera.”

Yahweh (YHWH) is one of the names given to the Judeo-Christian God.

Samaria, at that time, was the centre of the kingdom of Israel.

Teman was in Edom (now Jordan) – whose national God was named Qos.

The big debate remains – who (or what) was Asherah?

An answer is implied by the most dramatic positioning of that name.

It hints that original Jews didn’t believe in just one god.

It also seems to say their God – YHWH – was married.

REVELATION, OR DESECRATION?

On one jar, designated Pithos A, the inscription “Yahweh and his Asherah” sits above a stark image. It shows a couple wearing crowns and holding hands.

One is bigger than the other and flaunts a prominent penis. His companion has small breasts – though there may also be a faded penis or tail.

“It’s hard to make sense of the writing ‘YHWH and his Asherah’ without suspecting that this God, at least according to the people on this hill, was married,” writes Haaretz reporter Nir Hasson.

But not all Israeli academics agree.

Some argue the images are unrelated to the text and each other.

It appears the drawings were added to the jar at different times after the original inscription was made.

It may, they say, simply be graffiti intended to deface holy objects.

The God, they say, could be the Egyptian Bes – a ribald dwarf-god of war, partying and the home. This bearded deity is commonly shown with oversized genitalia.

Critics also argue “Ashera” is not a god or a wife.

Instead, it may refer to a tree – perhaps the one shown surrounded by ibexes on the same jar. Ashera is briefly mentioned in the Old Testament. Some translate it as being a sacred tree cut down before a war. Others argue it was the timber statue of a deity.

Like much of the Bible, the jury’s still out.

UNITING THE TRIBES

Archaeologists agree Kuntillet Ajrud was built during the First Temple era of Judaism.

An inscription on a bowl found among the ruins hints it may have been occupied by a priestly class. The Ancient Hebrew writing includes the words “holy”, “sacrifice” and “guilt-offering”.

What were Jewish priests doing in the desert, so far from home?

At that time, the Kingdom of Israel was in the north of the Holy Land – ruled from the city of Samaria. The Kingdom of Judah held the south. Its capital was Jerusalem.

Among the rubble of Kuntillet Ajrud was found what appears to be a picture of King Yoash of Israel. He had been victorious in a war with King Amatzia of Judah.

The outpost may have been founded by King Yoash. This would explain his picture. It would also explain how such a remote Israelite border outpost came to exist.

It may also have been part of an effort to unify a fractured religion.

Were the followers of YHWH preaching King Yoash’s northern doctrine to the rest of Judah’s scattered tribes?

A GOD OF MANY NAMES

A little more than 100 years after the time of Kuntillet Ajrud, King Josiah of Judah initiated a profound religious reformation.

Competing cults were banished. All sacrifice rituals were centralised and unified in Jerusalem. Any redundant holy site was demolished.

But echoes of this consolidation of the Jewish faith can still be found.

Some academics argue the Old Testament is, in fact, the result of an ancient attempt to amalgamate and harmonise a variety of different doctrines.

Literary structure, variations in names and different versions of the same event have been analysed and categorised. For example, contradictions in the book of Genesis about the day Eve was created as the result of the merger of two different traditions.

Supporters of this theory believe there were four original texts. One is called the Book of J (which names god Yahweh), another E (which names god Elohim), Book D (Deuteronomist histories) and Book P (Priestly roles, rituals and rules).

Do the Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions and images point to an original Yahweh cult, one unchanged by King Josiah’s interventions?

It remains in the realm of speculative possibility. But any answer remains tantalisingly out of reach.

Excavations at the site ended in the 1970s. And, in 1993, Israel handed over to Egypt all artefacts found there under the terms of a peace treaty.

No further study of the objects has taken place. But the potential significance of their message is keeping the potsherds in the public eye.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer. Continue the conversation @JamieSeidel