Hidden ‘cave popcorn’ leads to world’s oldest cave art discovery

A discovery hidden on a remote part of an island has stunned researchers who say it’s one of the oldest finds in the world.

It’s been described as one of the “coolest types of discoveries” because it was “hiding in plain site”.

Professor Adam Brumm, an archaeologist on a team behind the groundbreaking discovery revealed today, says what they believe is the world’s oldest known cave painting was “sitting right in front of our noses”.

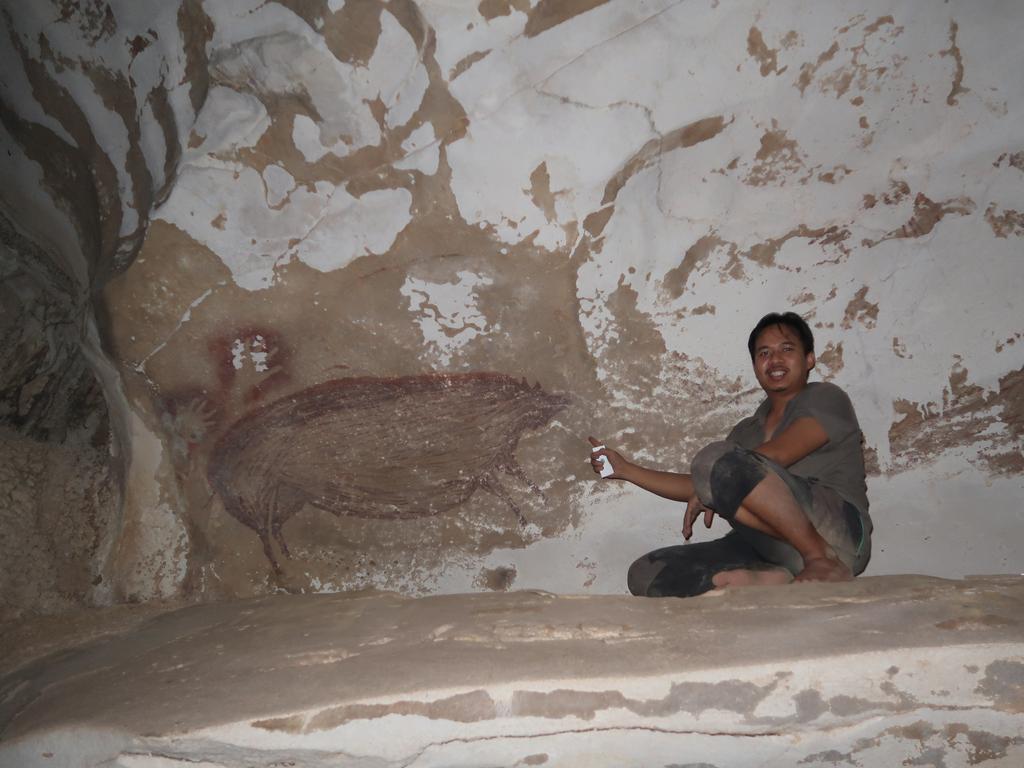

The Griffith University archaeologists uncovered a cave painting of a wild pig dating back to 45,500 years ago during field research in South Sulawesi in 2017.

It’s taken the team years of methodical work to publish their paper, out today in Science Advances.

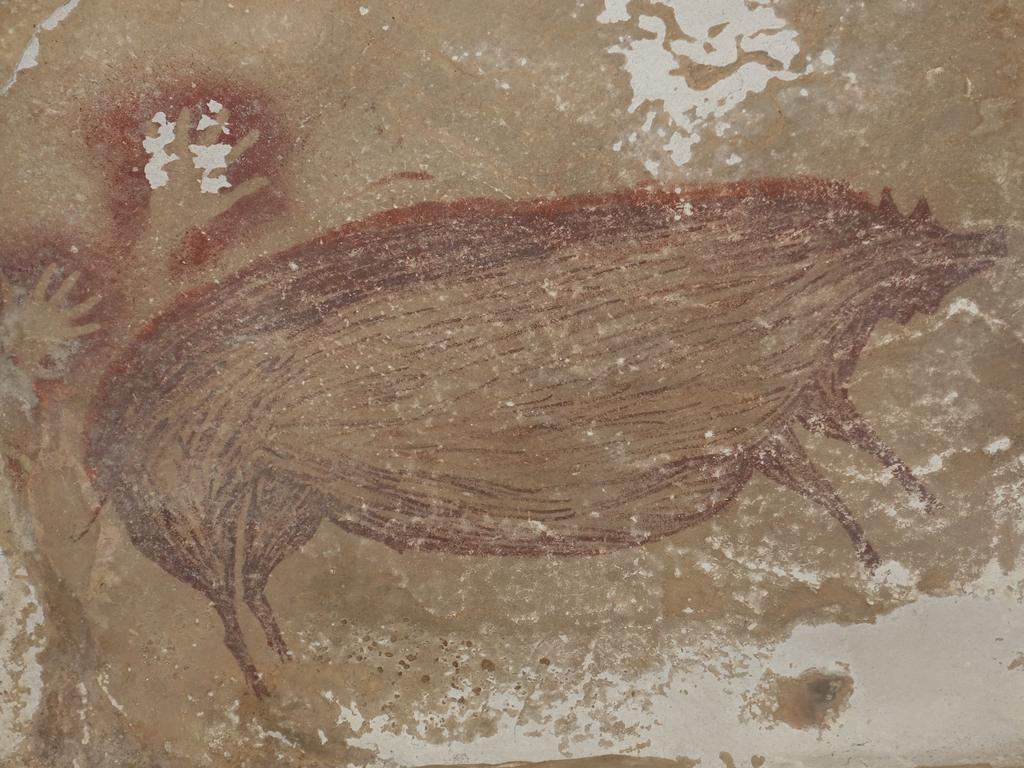

The cave painting consists of a figurative depiction of a Sulawesi warty pig, a wild boar that is endemic to this Indonesian island.

READ MORE: Follow our archaeology news

Professor Brumm said the secret location was uncovered in a “pristine, hidden valley” that, according to the locals, no westerners had been to before.

“It’s in a remote part of highlands with no road and there’s a challenging trek along a jungle path to get to it,” he said.

“Once you’re in this cave passage, it opens up to this incredible, beautiful valley which is inhabited by this tiny group of farmers in this incredibly isolated location.”

But Professor Brumm said they uncovered the location after working in an adjacent valley and hearing about the limestone cave of Leang Tedongnge from locals.

READ MORE: ‘Astonishing discovery’ at Stonehenge

He said the painting showed a pig with a short crest of upright hairs and a pair of hornlike facial warts in front of the eyes, a characteristic feature of adult male Sulawesi warty pigs.

“Painted using red ochre pigment, the pig appears to be observing a fight or social interaction between two other warty pigs,” he said.

The team previously published work in December 2019, dating a rock art ‘scene’ at least 43,900 years old, which was a depiction of hybrid human-animal beings hunting Sulawesi warty pigs and dwarf bovids.

That discovery was ranked by the influential journal Science as one of the top-10 scientific breakthroughs of 2020.

READ MORE: Victims of ancient eruption unearthed

The researchers use Uranium-series analysis of calcium carbonate deposits - or “cave popcorn” - that form naturally on the cave wall surface.

The latest analysis is at least 1500 years older than their previous discovery.

“In this case what we have is another narrative scene which is really cool, which seems to depict some kind of interaction between three wild pigs,” Professor Brumm said.

He said while the fourth image had deteriorated too much to depict, it was likely a pig.

Basran Burhan, an Indonesian archaeologist from southern Sulawesi and current Griffith PhD student, who led the survey that found the cave art, said humans had hunted Sulawesi warty pigs for tens of thousands of years.

“These pigs were the most commonly portrayed animal in the ice age rock art of the island, suggesting they have long been valued both as food and a focus of creative thinking and artistic expression,” he said.

READ MORE: Our 100,000 year war with ancestor

The latest work represents some of the earliest - if not the earliest - archaeological evidence for modern humans in the vast zone of oceanic islands located between Asia and Australia-New Guinea – known as ‘Wallacea’.

“Our species must have crossed through Wallacea by watercraft in order to reach Australia by at least 65,000 years ago,” said dating specialist and team co-leader Professor Maxime Aubert.

“However, the Wallacean islands are poorly explored and presently the earliest excavated archaeological evidence from this region is much younger in age.”

The team expects that future research in eastern Indonesia will lead to the discovery of much older rock art and other archaeological evidence, dating back at least 65,000 years or possibly earlier.

Professor Brumm said the discovery underlined the remarkable antiquity of Indonesia’s rock art and its great significance for understanding the deep-time history of art and its role in humanity’s early story.