Antikythera mechanism expedition begins search for missing fragments of world’s oldest known computer

WITH torn sails and splintered timbers, a Roman ship foundered in the savage seas off Greece. Some 2000 years later, what it carried would rattle the world.

WITH torn sails and splintered timbers, a Roman ship foundered in the savage seas between Greece and Crete. Some 2000 years later, what it carried would rattle the world.

As the shattered remains sank into the dim sea, the treasures it carried passed out of reach of history.

As Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem Ulysses evocatively intones: “Beyond the utmost bound of human thought”.

Until now.

On board was an amazing but eclectic collection: Bronze and marble statues. Glassware. Jewellery. Coins.

An ancient computer.

But the cargo also appears to have been something of an assortment of parts. Few objects recovered so far have been complete.

Was it a treasure ship making a delivery to an expectant king or high priest? Was it a loot ship, carrying the spoils of a distant war? Or was it a salvage barge lugging away the discarded, unfashionable luxuries from a rich estate for recycling?

What vanished that fateful day about 60BC is about to be revealed.

Finely formed bronze statues of gods, kings and warriors. Amazingly animated marble statues — made weak by time and fate, but still full of vigour and life. Sublimely crafted and coloured glass bowls and cups.

All this paled into insignificance once scientists took at close look at a corroded clump of bronze cogs and wheels.

It was part of an astronomical calculator. A mechanical device to predict the motion of the stars and planets.

The 82 fragments recovered so far have become known as the Antikythera Mechanism. It has been the centre of fascination, debate and speculation for decades. And there are enticing hints that there may be a second.

Now archaeologists have resolved to find the rest of it.

It was more than a century ago when local sponge diver spotted an eerie hand sticking out from the silt while working the barren crags off Point Glyphadia on the Aegean island of Antikythera.

The intrepid divers could only go as deep as 75m for a few minutes. Nevertheless, they managed to recover a wealth of ancient art.

But it would be one shapeless, nondescript lump of bronze which would turn out to be one of the most extraordinary discoveries in history.

When eventually cleaned, the 20cm tall tangle of bronze revealed a complex interweave of gears and cogs.

CLICK HERE to see the enhanced version of this story

Today an assembly of archaeologists and divers sets out with hungry hearts to finish the job.

It won’t be an easy task. And they have only a month to do it in.

Antikythera isn’t exactly a hospitable place. It’s little more than a clump of rocks situated between Crete and Greece. The earthquake-wracked region is renowned for its jagged outcrops and deep ravines.

But new technology will be instrumental in this search for the old.

It’s a cutting-edge piece of engineering which encases an operator inside an automated exoskeleton pressure suit. It can keep its occupant safe — and mobile — down to a depth of 300m for up to five hours at a time.

On the way to #Antikythera: http://t.co/chXYlaL3xD pic.twitter.com/46yLl09baa

— Antikythera Divers (@antikytheradive) September 14, 2014Dr James Hunter, a research fellow with the South Australian Maritime Museum and head archaeologist for the HMCS Protector Project, says he is excited at the potential the exosuit brings.

“It’s really cool. We’ve progressed quite a bit from the early days of underwater archeology when we were using scuba gear with regular compressed air and no mixed gas. We’ve learned through trial-and-error new methods to safely work at depth,” he says.

Jacques Cousteau revisited the depths in 1953 and 1976 using just such basic equipment. Nevertheless, the famous ocean explorer managed to dredge part of the site — recovering many wonderful things.

It is still believed the main body of the wreck itself has not been extensively searched.

A recent survey uncovered evidence of artefacts scattered over a 50m by 10m patch of the seabed.

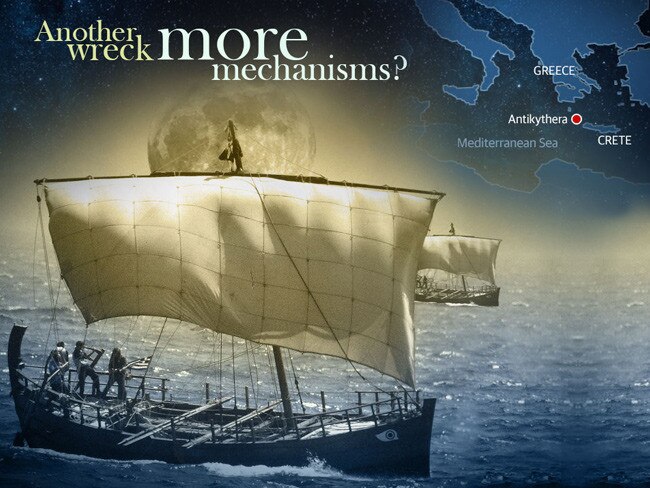

Then there’s a second, as-yet unexplored wreck.

Dr Brendan Foley, archaeologist with the Massachusetts-based Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and leader of the new expedition, says the new wreck was 250m away from the first site and appeared to be carrying similar ceramic objects.

“We discovered it about two years ago,” he said. “It was obviously following the same route and may have been travelling with the ship carrying the mechanism.”

The new expedition hopes to get down and dirty, digging underneath the original wreck as well as further exploring the debris trail that extends up to 150m from the ship.

The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project is a collaboration of international academics with the declared purpose of fully recovering the Antikythera Mechanism.

“I am so excited that I often find myself wide awake thinking of the shipwreck,” Dr Foley told a function at a recent exhibition of the 378 artefacts so far recovered.

Dr Hunter is equally keen.

“The mechanism is certainly centre stage, but the information potential in other areas is pretty extensive as well,” he says.

Along with more of the mechanism, Dr Hunter is hoping for the mundane: Traces of fabric and food — anything which gives us a better idea of the lives of those associated with the ships.

“Because that’s really the goal, what they’re trying to find out,” he says. “The artefacts are important, but it’s what they tell us about the people who made and used them that matters most.”

Stories of cities, of men and manners, climates, councils, governments.

From the eternal silence of the seabed, Dr Foley is confident of finding something more.

“We can speculate that there are more items to be found from its valuable cargo, which will most likely be very well preserved,” he says.

“We have feet, arms and the crest of a warrior’s helmet from statues recovered in 1900 — maybe we’ll get lucky and find the rest of them,” Foley told New Scientist.

“But for me, the mechanism is what sets this wreck apart. It’s the questions it opens up about the history of science and technology that fire my imagination.”

It’s one of archeology’s most astonishing finds: A mysterious bundle of cogs and wheels pulled from the depths of the Aegean Sea.

It’s the most sophisticated device ever to emerge from antiquity.

It’s taken decades of study to decode exactly what it does

Astrolabe? Orrery? These are words little used in the modern world which apply to forms of an astronomical clock.

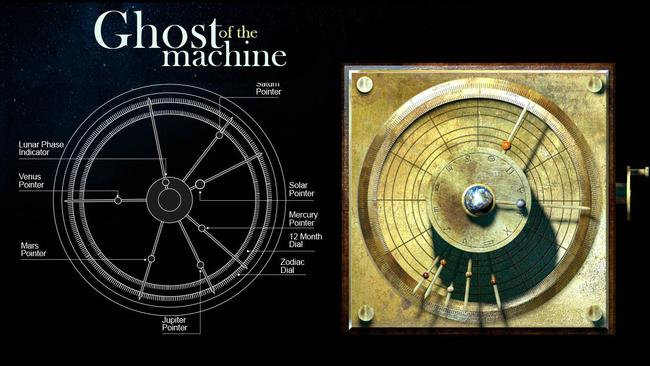

The Antikythera mechanism is an analog (meaning built of cogs and dials) computer from the ancient world.

It’s the only known example of its kind.

“The device is obviously amazing and makes mechanical what had been known for a millennium or more in terms of astronomical cycles,” Professor Roger Clay, an astrophysicist with the University of Adelaide says.

“Those cycles had been defined for eclipse prediction and to produce a workable calendar, the latter being a major practical necessity. The fact that these cycles were even known is amazing since each complete cycle was longer than the average life expectancy.”

We know it was a hand-cranked device specifically designed and built to predict the cycles of the sun and moon — and their eclipses. It seems likely to have helped determine which city was due to host the ancient Olympic Games, as well as track the movements of planets across the sky for the purpose of prophecy and religious ceremony.

It is an incredibly complex device and represents a level of skill not matched again until the 14th century.

“I imagine that you are right to imply that this mechanism was a rich person’s device,” Dr Clay says. “ It isn’t necessary for doing the calculation but it does allow anyone to do it. In effect, it is an early app!”

From the scraps we have, some 30 gears have been identified so far — the largest being about 14cm wide and holding 223 teeth.

But much of the ancient machine is missing.

“Surprisingly what the real issue was that bronze got recycled,” Dr Hunter says. “You melted it down. You had a statue of Zeus or whatever, and it’s like — we don’t need that any more, let’s take all that bronze, melt it down and make something else …”

The good news is that bronze generally holds up very well under water.

“They reckon they’ve got half of it,” Dr Hunter says. “That would seem to suggest that the other half has to be down there somewhere ... either that or the cargo may have been scrap!”

It’s a foreboding thought.

“It’s interesting that the ship was carrying a lot of bronze, particularly a lot of bronze in pieces,” Dr Hunter says, “so it begs the question: Was this ship carrying a big pile of scrap to recycle it?

“I’d prefer to believe hat the ship was carrying an intact cargo of luxury goods and personal belongings, but it’s important to keep an open mind and not rule out other, more mundane possibilities.”

Only once the final pieces are in hand can archaeologists — and astrophysicists — make it shine in use again, and finally discover exactly how advanced this ancient piece of clockwork really was.

Somewhat appropriately, the $3 million expedition to find them is being part-sponsored by a Swiss watchmaker.

The seven main and 75 smaller fragments that have been identified are now housed in the National Archaeological Museum, in Athens. This institution is part of the new search.

The most in-depth analysis of the remains was conducted in 2005. It took an international effort to peer past the corrosion and map the cogs in three dimensions without damaging the objects themselves.

It revealed astonishing detail.

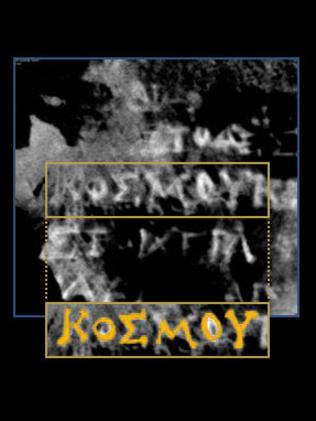

Even fine and worn inscriptions on the surface of some of the bronze work were exposed.

These have since been read.

One word stands out clearly: ΚΟΣΜΟΥ, meaning “cosmos”

One metal plate may even have been part of an ancient instruction manual. Fragments of writing appear to detail different gear settings for the device.

But now there is a new complicating factor.

Michael Wright, curator of the Science Museum, in London, was one of those who made a careful X-ray map of the fragments.

When he set out to create an exact replica, he discovered one set of gears and cogs did not match the rest.

“It’s not easy to find a place for one piece, Fragment D,” he told New Scientist. “It’s also slightly different in workmanship and has a slightly different colour.”

He now believes there may be more than one computer amid the mud of the sea floor off Antikythera.

“What can be hiding down there? Just think how such discoveries could change the way we view the ancient world and especially the Greek civilisation,” Dr Foley said.

The key to finding the remains of the ancient piece of engineering is a new one: An Exosuit.

Essentially a wearable submarine, it will allow an operator to dive as deep as 300m and work there for more than five hours.

“Now we can have an archaeologist in the suit for hours, and we’ll only have to come up to answer the call of nature,” Dr Foley says.

The original sponge divers were able to go as far down as 75m for just a few minutes. Some of those who dove on the Antikythera site became paralysed. One died.

Divers in this new expedition will spend much of their day operating between 50m and 75m. The suit is expected to go down as far as 120m.

It may look unwieldy, but the $1.7 million exoskeleton is ideally suited to recovering fragile deep-sea artefacts.

But it’s the personal touch it offers that counts the most, says Dr Hunter.

“The exosuit has the advantage of actually having an archaeologist there on site. When you’re dealing with sites remotely, it’s sometimes difficult to gauge what’s happening when you’re looking through a tiny monitor. If you’ve got someone who’s actually there, they’ve got a fair degree of visibility through the helmet and they’re looking directly at what they’re dealing with in real-time. That’s ideal.”

Pedals at the feet of the suit allow the diver to fly through the water using thrusters built into the suit’s backpack. These can even be controlled via remote control from the surface.

The heavy arms are articulated and finely balanced, allowing their arms to move freely.

Instead of hands, objects will be grasped by mechanical pincers.

An umbilical cable is attached to the ship carries data cabling for video and voice feeds as well as providing power for the thrusters and the carbon dioxide scrubber which allows the divers to stay down for so long. A backup battery powers the breathing and communications systems in an emergency.

The pressure is on.

Customising the suit to “fit” individual divers is not easy, and its operators need time to adjust to its controls, balance and weight.

While the expedition is scheduled to be conducted for a full month, the suit itself will only be on loan to the archaeologists for a little more than a week.

The plan is to carefully map the wreck sites before deploying the armour-encased archaeologist.

“It’s an experimental suit,” Dr Foley said. “We need to figure out what it can do for us and how to make it as effective as possible.

“Over a period of meticulous sessions, we’ll slowly close in on what we hope is another mechanism.”

Whatever the case, the results of the expedition will keep archaeologists busy for quite some time. And there are hundreds more as yet unexplored wrecks offering potential insights into ancient lives.

“There’s a lot out there,” Dr Hunter says. “And there’s a lot we haven’t even come close to getting to yet. “

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.