‘Anomaly’ in radar image taken near Egypt's Great Pyramid points to discovery of long-lost tomb

Archaeologists could be on the verge of a major discovery after a radar detected a “anomaly” near the Great Pyramid. Here’s what they think the mystery structure is.

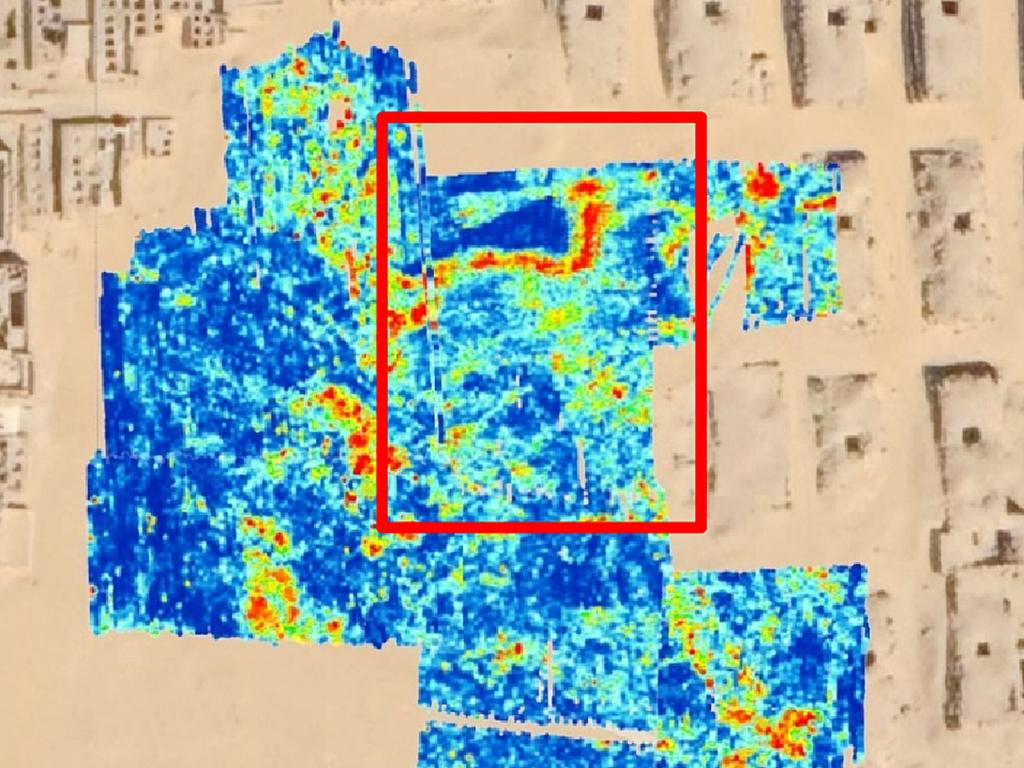

A ground-penetrating radar “anomaly” among Egypt’s pyramids at Giza has fired up hopes of the discovery of a long-lost tomb.

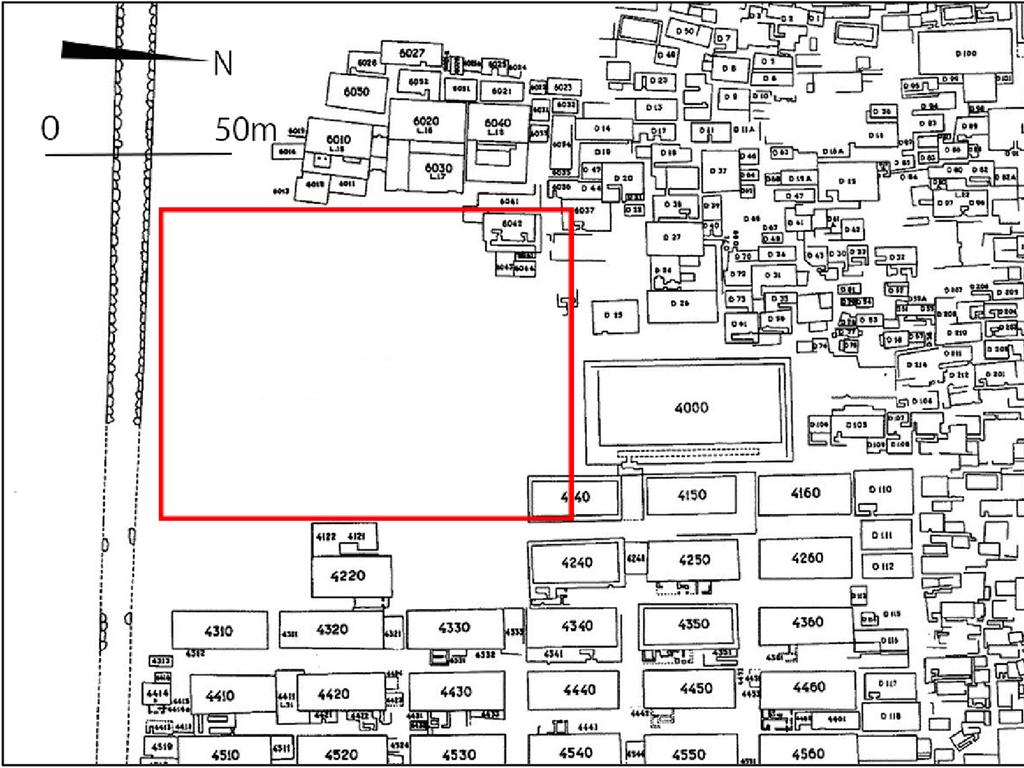

The mysterious underground structure was detected by a joint Japanese-Egyptian team of archaeologists in the shadow of the world-famous Great Pyramid and Great Sphinx.

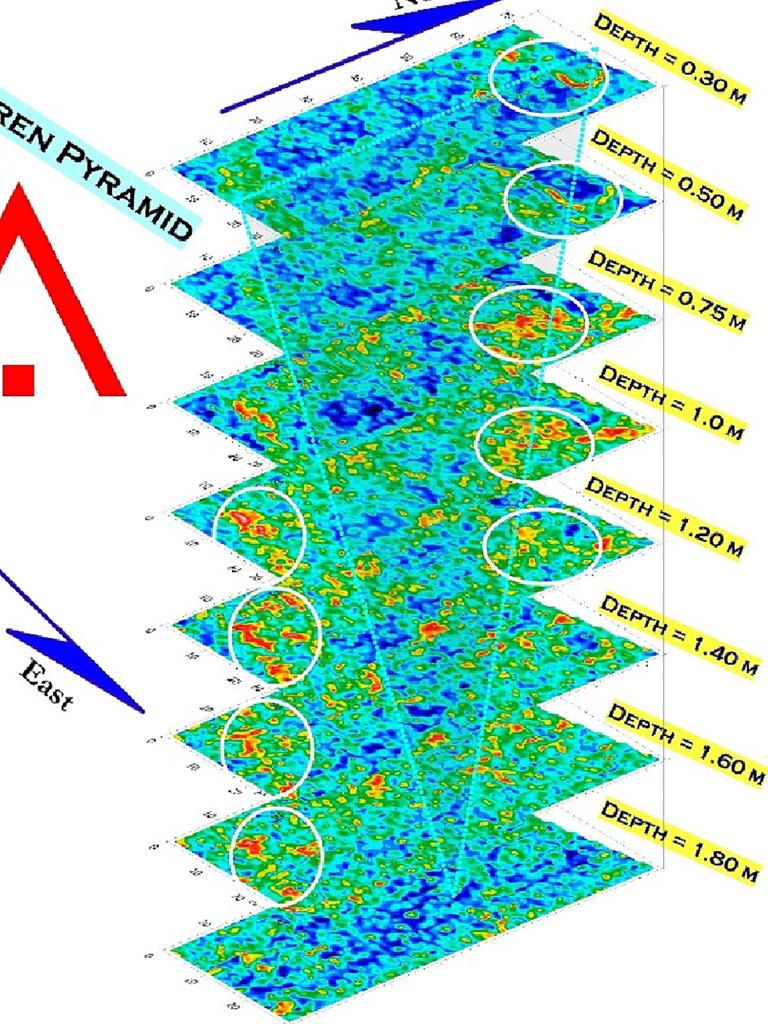

Their report, published in the Archaeological Prospection journal, describes an “L”-shaped 10m by 15m structure buried 50cm to 10m beneath the desert sands.

“We believe we found an anomaly: a combination of a shallow structure connected to a deeper structure,” the researchers, led by Professor Motoyuki Sato of Tohoku University, write.

“We conclude from these results that the structure causing the anomalies could be vertical walls of limestone or shafts leading to a tomb structure.”

Buried bureaucrats

The anomaly was detected and mapped as part of a survey of a flat, apparently unoccupied space that had not previously been extensively examined. But it is associated with the burials of extended Egyptian royal family members and high-ranking officials.

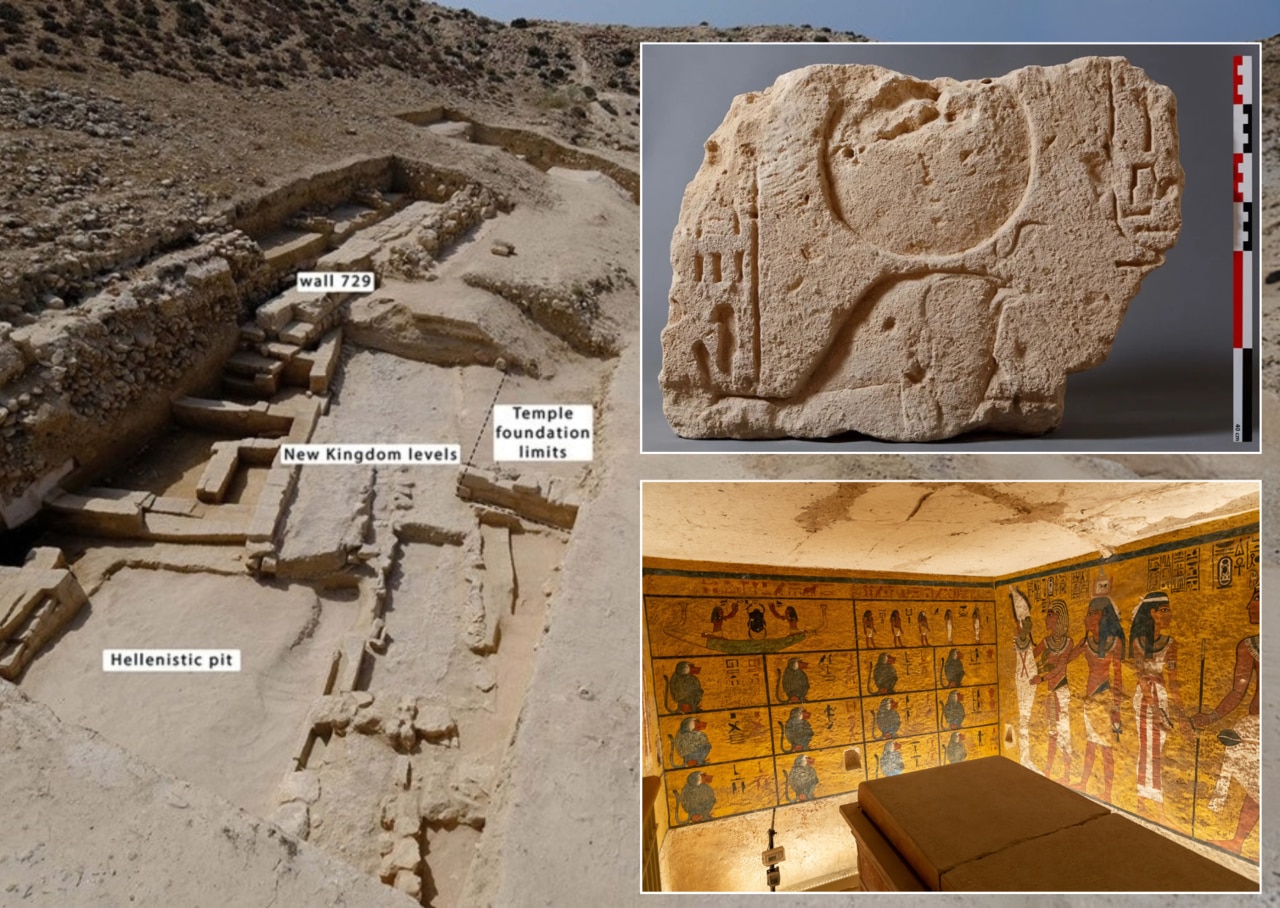

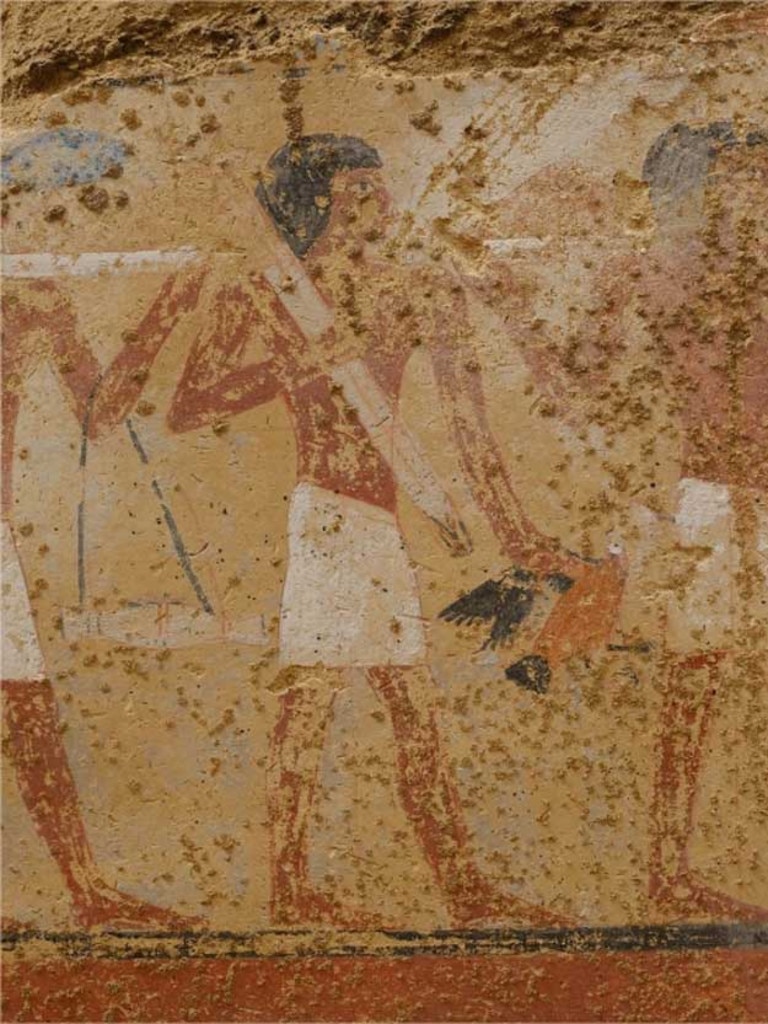

In early dynastic periods, these notaries qualified for a “mastaba” (a box-like flat-roofed precursor to the pyramids) to protect and guide them through their journey to the afterlife.

“A mastaba is a type of tomb, which has a flat roof and rectangular structure on the ground surface, constructed out of limestone or mudbricks,” the study authors write.

“It has a vertical shaft connected to a subsurface chamber.”

In this case, the above-ground portion of the tomb - usually a funerary chamber made of cut limestone blocks or mud brick - appears to have been demolished long ago.

“We observe quite a lot of limestone particles on the surface of this survey area,” the study notes.

If it were to be a mastaba, an exploratory excavation should expose large limestone blocks of the shallow entry shaft.

“We believe that the continuity of the shallow structure and the deep large structure is important,” it adds. “From the survey results, we cannot determine the material causing the anomaly, but it may be a large subsurface archaeological structure”.

Another 4300-year-old Old Kingdom mastaba is the subject of an ongoing German Archaeological Institute excavation in Dahshur, just south of the Great Pyramids.

The mudbrick monument, built for administrator “Seneb-Neb-Ef” and his priestess-wife Idet, dates back to about 2300 BC and the end of the Fifth Dynasty.

Egyptian antiquities chief Hisham al-Leithy says inscriptions and scenes depicting grain harvests and ships on the Nile have been recovered at the site.

Sifting the sands of time

The invention of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) techniques has contributed significantly to new discoveries in recent decades at sites including Britain’s Stonehenge.

In this instance, a survey using both techniques in 2021 and 2022 was used to construct a 3D representation of the underground “anomaly”.

“Most such sites are buried under overburden sand, and it is not easy to locate their exact positions from the surface. Under such conditions, their positions can be identified by the shallow geophysical exploration methods,” the study stated.

Neither ground-penetrating radar nor electromagnetic sensors are capable of revealing the precise cause of subsurface reflections.

But they do define the shape of reflective or high-resistance areas.

Its use and interpretation can be controversial, however.

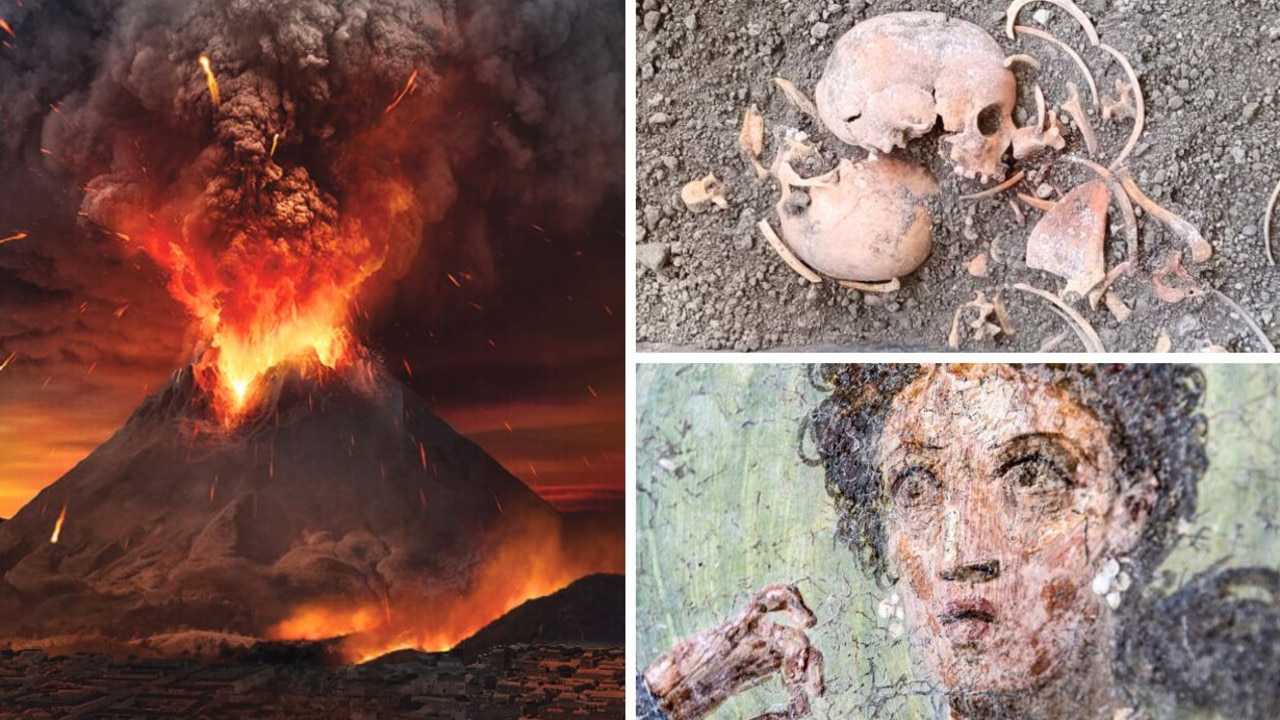

A series of surveys of Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s (King Tut’s) tomb have produced conflicting results regarding the presence of a “hidden chamber” - speculated to be the burial site of his beautiful mother, Queen Nefertiti.

A 2015 scan by a Japanese ground-penetrating radar expert, Hirokatsu Watanabe, produced what he called two rooms containing “metallic” and “organic” objects. Follow-up scans in 2016 and 2017 produced nothing. But a fourth, in 2019, recorded “anomalies”.

No further research has since been published.