Problem Australia needs to solve before ‘it’s too late’

In new research, scientists have looked at 30 years of data and made a concerning find about something very important to Australia.

Scientists have made a startling discovery about something quintessentially Australian.

While they don’t tend to make headlines and you certainly can’t cuddle them for tourist photos, the plight of the platypus has been highlighted in new research out today.

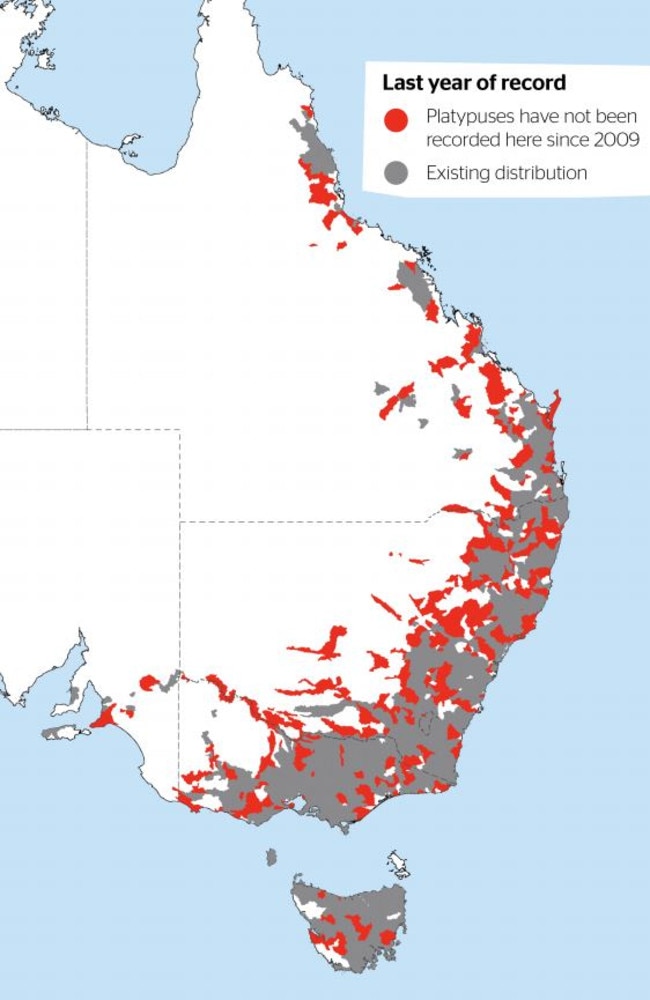

The study led by UNSW Sydney reveals the parts of Australia where platypuses are found has shrunk by at least 22 per cent - or about 200,000sq km – an area almost three times the size of Tasmania – in the past 30 years.

The find means the beloved Aussie animal is now likely to meet the criteria for listing as a threatened species under Australia’s national environmental law.

“There is a real concern that platypus populations will disappear from some of our rivers without returning, if rivers keep degrading with droughts and dams,” Professor Richard Kingsford, a lead author of the report and the Director of the Centre for Ecosystem Science at UNSW, said.

“We have a national and international responsibility to look after this unique animal and the signs are not good. Platypus are declining and we need to do something about threats to the species before it is too late.

“Protecting the platypus and the rivers it relies on must be a national priority for one of the world’s most iconic animal.”

RELATED: What we face losing under climate change

As a result of their findings, UNSW researchers, along with the Australian Conservation Foundation, WWF-Australia and Humane Society International Australia, today nominated the platypus to be listed as a threatened species under Commonwealth and NSW processes.

“While our national environmental laws should be much stronger, listing the platypus as a threatened species is a critical first step towards conserving this iconic Australian species and putting it on a path to recovery,” said Dr Paul Sinclair, campaigns director at the Australian Conservation Foundation, which commissioned the research.

The research found the decline in numbers was most severe in NSW with a 32 per cent reduction and Queensland with 27 per cent.

While Victoria recorded a state-wide decline of 7 per cent, that number is much higher in some Melbourne catchments.

There have been reductions of 18–65 per cent in some catchments since 1995.

The researchers said declines in platypus observations were worst in places where natural river systems and water flows had been most heavily modified, such as the Murray-Darling Basin.

New dams, the over-extraction of water from rivers, land clearing, attacks by foxes and dogs, pollution and suburban sprawl are the main factors driving the decline.

RELATED: How we can save our wildlife from extinction

Platypuses also drown in closed freshwater traps designed to catch yabbies and fish, which are still legally sold in NSW and Queensland.

The changing climate also presents a serious new threat to platypuses, with more severe droughts, reduced rainfall and intense fires drying out rivers and river vegetation.

“The platypus is one of the most unique and archaic mammal species in existence, and this research along with recent advice to list the species as vulnerable in Victoria makes it abundantly clear there’s no time to waste in increasing their protection,” said Evan Quartermain, head of programs at Humane Society International Australia.

Dr Stuart Blanch, senior manager of land clearing and restoration at WWF-Australia said platypuses were to rivers what koalas were to forests.

“These days a sighting of just a few platypuses is often associated with a healthy population, but historical records suggest today’s numbers are only a fraction of what they once were,” he said.

“This alarming decline is the wakeup call we need to better protect our rivers and creeks.”

RELATED: Five key species Aussies should protect to save the environment

Platypuses need healthy rivers and streams where they can swim and forage for food around riverbeds and riverbanks.

They have traditionally been found from Tropical North Queensland all the way down the east coast to Victoria and across most of Tasmania.

The research was led by Dr Tahneal Hawke, Dr Gilad Bino and Professor Richard Kingsford of UNSW Sydney.