‘You are like a celebrity to me’: When women cyberstalk women

IT STARTS with a friendly email out of nowhere, but quickly turns nasty. This is what happens when an obsession goes too far.

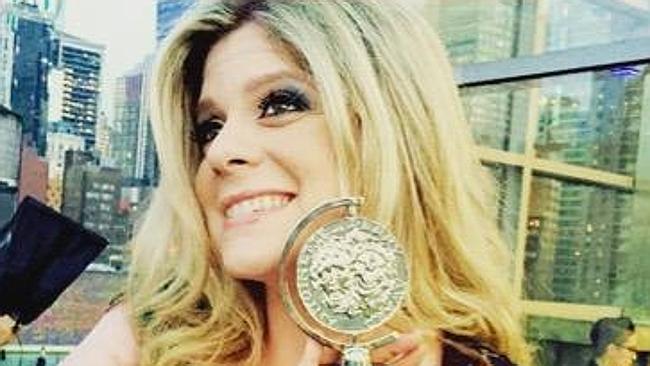

WHEN Melissa Anelli emailed a woman who was causing troubled on her Harry Potter fansite, she couldn’t imagine the hell she was about to set loose.

“I will hunt you down like the dirty, fat cow you are and slit you from ear-to-ear,” came the furious reply. It was the start of a five-year campaign of harassment by New Zealand woman Jessica Parker, who sent Melissa a barrage of death threats, fawning apologies and admissions of love and sexual attraction.

“As long as you refuse to deal with me, I’ll remain being that little demon on your shoulder,” Parker wrote in one message. “I can’t be denied forever, you will give yourself to me in bed one day. Else I will return to your home and flay you alive. Your soulmate.”

Melissa, webmistress at The Leaky Cauldron, was active in her online community, appearing in YouTube videos and podcasts, and posting to several popular social media accounts. Jessica used all of them to get to her.

“If I was a rock, she was like water being poured over me,” Melissa told news.com.au. “She found every way in.

“She’d send postcards to my mother’s house, my father’s work and my sister’s apartment on the same day. She sent my nephew a doll with the message, ‘Enjoy your family while you can.’”

Parker sent Melissa photos of her apartment and even took a trip to her hometown of New York, blogging about taking a bus near her house. “The beginning was the scariest,” said Melissa. “I would wake up in the middle of the night not sure if I’d locked the door, thinking I’d heard noises. I called the police twice, You think, there’s a psychopath out there.

“All the reassurances — just get off the internet, turn off the computer — don’t make sense when you’re dealing with someone irrational.”

After the police told her they couldn’t issue a restraining order unless her stalker was outside her door, Melissa contacted the FBI. They took it seriously. When fan events approached, Parker would ramp up the threats, telling Melissa “I’ll find you”. The FBI began organising for ex-Marine bodyguards to escort her when she travelled outside the US.

Eventually, Melissa got in touch with a detective in New Zealand, who told her Parker had previously been arrested. She now forwards all threats to the force, and keeps all information about her private life offline.

Melissa wants the world to recognise that this happens, but she still manages to feel some sympathy for Parker. “When I ask myself, ‘why me?’, I have to tell myself she’s a sick individual, logic doesn’t apply. It isn’t sexual attraction, even if there are sexual overtones. It’s obsession, mental illness.

“I think she identified with what I did on the internet. When people get obsessed with YouTube stars, even standard celebrity worship, it’s based on the idea you know someone.”

All Melissa wants now is to be safe.

Scientist Emily Lakdawalla had a similar experience when she received an effusive email from a stranger insisting they should become friends. “I have tremendous respect and admiration for you,” wrote Sophie*. “We should get together for dinner sometime ... I’d like us to be great friends.”

The writer said she wanted to emulate Emily’s success, and was studying for an astronomy Master’s online. Emily recognised Sophie’s name as one that had been banned from forums she used for constantly interrupting discussions to return to a theory she obsessed over.

“I generally don’t meet people for dinner who I don’t know,” Emily told news.com.au. “Especially not someone who’s displayed troll-like behaviour.”

She ignored the email, but the next day, she received the same message again, slightly modified. “Believe it or not, you are like a celebrity to me,” it read. “Meeting you is one of my life’s dreams.”

Sophie offered to donate to The Planetary Society, where Emily writes, if her idol met her for dinner, copying in the organisation on her email. “If felt very strange and creepy,” said Emily.

But things were about to get weirder. In the face of Emily’s continued silence, Sophie sent her an invite to her backyard birthday party on the east coast. Then she appeared at a conference Emily was attending, following her into the women’s bathroom.

“She tried to introduce herself through the door of the bathroom stall,” said Emily. “I felt exceedingly uncomfortable.”

With Emily continuing to ignore her, Sophie began leaving posts on forums around the internet, calling her biased and a “shill”.

Having received the first email in 2009, Emily is convinced “she’s not going to go away.” The police are unlikely to intervene unless Sophie’s behaviour becomes more threatening, but Emily is very aware “someone with an obsession could escalate their behaviour”.

While we often hear about men harassing women online, and even women cyberstalking men, it’s rarer to hear about all-female cases. But more stories of intimidating behaviour directed at women, by women, are emerging.

Writer and former escort Charlotte Shane this week wrote on Broadly about how she “received regular emails from women eager to start a friendship or receive mentorship from me, and they almost always made me uncomfortable.”

Her female fans would act as if they were already intimate friends with Charlotte, before turning on her when she refused to engage and threatening to expose her identity to her clients.

Charlotte compared her experience to that of blogger Cynthia*, who began receiving troubling comments from an over-zealous fan. “I’m literally crying right now with jealousy,” the messages read. “Why is your life so perfect?”

After responding jokily, Cynthia tried to gently tell her to stop, and the fan turned nasty, leaving comments calling her ““wannabe earth mother bitch from hell” and “stuck up pig whore” and spreading rumours she was cheating on her husband — even emailing him from an anonymous account to tell him so.

What’s unusual about these female stalkers is that their attachment appears unrelated to romantic or sexual desire, and more about a compulsion to emulate the object of their affection.

“A lot of times, this develops around feelings of rejection,” Jean Twenge, author of Generation Me, told news.com.au. “One woman wants to be closer than the other and that turns into obsessive feelings.

“Reading about another person’s life creates a feeling of intimacy. People will post comments on a blog or a message board, it can begin innocently, but if one person feels slighted, it can go wrong very quickly.”

In a world of beautiful, filtered Instagram photos, it’s not too much of a stretch to see how some women become fixated on others with seemingly perfect lives. Yet female stalkers can be frighteningly sexual and violent as well.

In 2006, Lori Drew was exposed as the woman behind a fake MySpace account that persuaded 13-year-old Megan Meier to take her own life.

In another disturbing case, journalist Joanne Lee was stalked by a woman who believed she was the writer’s husband and father of her child. Amy Chua sent Ms Lee hundreds of rambling, nonsensical letters and emails and left long, slurred emails declaring her love or making obscene accusations about supposed infidelity.

Ms Lee filed three police reports over two years, but the harassment continued until she became too afraid to leave the house, and was forced to quit her job at the Straits Times.

In a landmark case, Twitter ‘troll’ Isabella Sorley, from Newcastle, made it clear that women are capable of as much vitriol as men online.

The 23-year-old was given eight weeks in jail for bombarding bank note campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez with comments including “die you worthless piece of crap”. Ms Criado-Perez said the abuse had been “terrifying and scarring”.

Ms Twenge said that while men are typically angered by rejection and women obsessed or hurt, anonymous people are more likely to be aggressive, explaining the cruelty that appears online.

“You would think people would express sadness and anger outright, but it comes out in dysfunctional behaviour such as aggression and obsessive behaviour such as emotional eating.

“People are trying to make themselves feel better by upping their positive emotions, then they have the negative feelings.”

Online, other people become dehumanised and we can feel at once closeness and a distance.

It’s when this turns sour that some people take it too far.

When does social media stalking cross the line? Share your experiences by emailing emma.reynolds@news.com.au.