Dark Mofo plan to cover British flag in Indigenous blood cancelled as Leigh Carmichael apologises

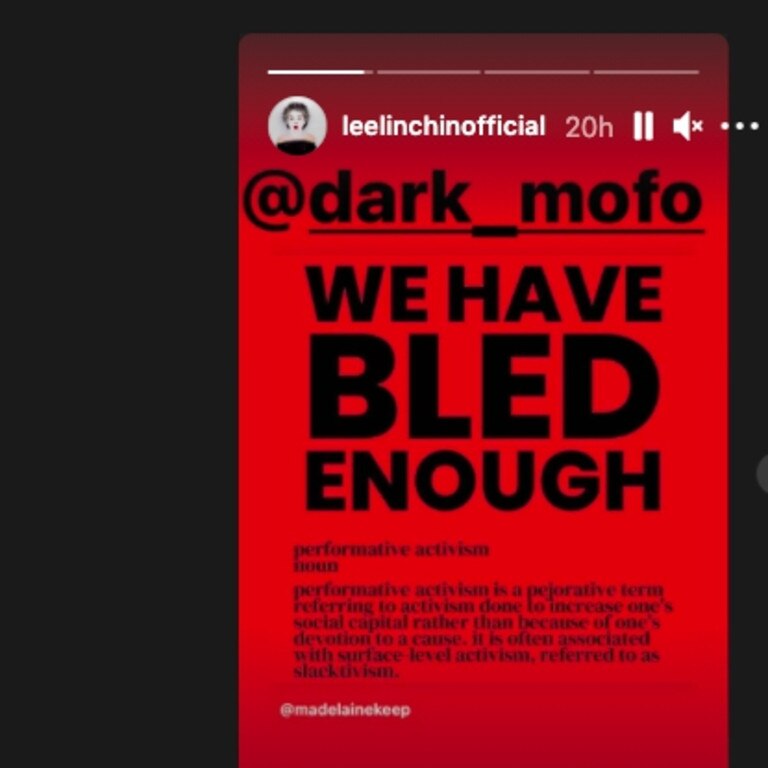

You’re not looking at a Red Cross appeal; this poster calling for blood had a different purpose – one that’s now been cancelled.

The creative director of an edgy winter art festival held at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art has now apologised on behalf of the festival after previously defending plans for an “insensitive” stunt that’s been criticised as a “terrible idea”.

After defending the artwork on Monday, Leigh Carmichael posted again on the Dark Mofo Facebook page on Tuesday afternoon that the festival had reconsidered and now believed “the hurt that will be caused by proceeding isn’t worth it”.

“We made a mistake, and take full responsibility. The project will be cancelled.”

“We apologise to all First Nations people for any hurt that has been caused. We are sorry.”

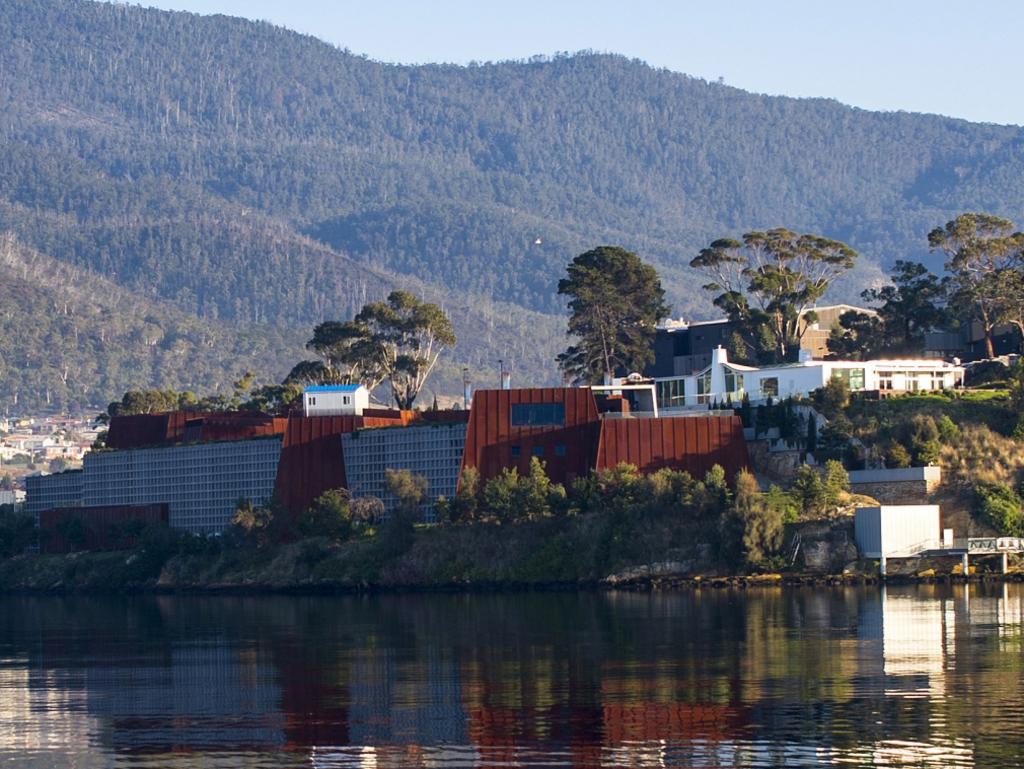

At this year’s Dark Mofo festival in June, Spanish artist Santiago Sierra had planned to immerse a Union Jack flag in around 39 litres of blood from 83 people indigenous to nations colonised by the British Empire, which includes Australia.

Under a post announcing the project, complete with an on-brand-for-MONA poster that said “We Want Your Blood”, the public blasted the idea.

RELATED: Star’s tears after Kmart doll mistake

RELATED: Secret behind JB Hi-Fi’s ‘most stolen’ item

“Perfect example of ‘woke’ people trying to make a point and absolutely missing the mark,” wrote one commenter who called it a “terrible idea”.

“The respect and sensitivity has obviously been lost on the part of Santiago and Dark Mofo. There are other ways to be Edgy in Art. Disrespecting a culture that you don’t belong to isn’t one of them,” wrote another critic.

Another said “that flag has been soaked in First Nations blood on this land enough”.

RELATED: Annoying ‘feature’ coming to app

RELATED: Musk sued over ‘erratic’ tweets

Some dismissed it as a marketing stunt to appeal to people who would have gone to Dark Mofo anyway, with one calling “this bumbling effort … an attempt to promote the whole shebang to get the punters who have them on a pedestal through the door” while others said the blood would be better off in the Red Cross blood bank.

Others went to an older post from a few months ago on the Dark Mofo Instagram page expressing solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, where some expressed shock at “the f***ing audacity” and another labelled Dark Mofo a “gammon ally”.

In his original post that preceded the apology by about 20 hours, festival director Leigh Carmichael said Dark Mofo had been “overwhelmed with responses”.

RELATED: Seven letters that get you banned

RELATED: ‘Disgusting’: Melbourne bar apologises

While he wasn’t yet saying sorry, Mr Carmichael said the festival “understand, respect and appreciate the many diverse views in relation to this confronting project”.

In an interview with The Australian, Mr Carmichael said the project had stoked heated internal conversations.

“We’ve been debating and arguing about it for a year now and there are some really strong views within my team that we shouldn’t be proceeding,” Mr Carmichael said.

According to the Australian those debates and arguments were over whether or not to use the British flag.

RELATED: Fashion house sues Insta account for $867m

Many questioned whether the project had any input from local Indigenous people, whom Mr Sierra planned to “work with … to understand their point of view” but not “collaborate” with, according to Mr Carmichael.

Mr Carmichael said the festival had “conversations” with Tasmanian Aboriginal people prior to announcing the project, and those “conversations” reflected the “range of perspectives” that others had shared in the wake of the announcement.

He defended the project saying “self-expression is a fundamental human right and we support artists to make and present work regardless of their nationality or cultural background,” adding “it’s not surprising that the atrocities committed as a result of colonising nations continue to haunt us”.

Some used that fundamental human right of self-expression to mock the since cancelled plan through memes and cartoons on social media, comparing the festival curator to a vampire and characterising the stunt as a patronising attempt to educate Indigenous people on their own history.

A website calling for Indigenous people to donate their blood listed Mr Carmichael and a French man named Olivier Varenne as the curators of the cancelled project.

The Spanish artist Santiago Sierra said “the use of the British flag is not about any specific people, but rather seeks to reflect on the material on which states and empires are built”.

“The use of First Peoples’ blood from different populations, and its indiscriminate mixing, has impact within the act itself – all blood is equally red and has the same consistency, regardless of the race or culture of the person supplying it,” Mr Sierra added.

He also noted “the First Nations people of Australia suffered enormously and brutally from British colonialism. Nowhere more so than in Tasmania,” where MONA is based.

TASMANIAN APOLOGY FOR ABORIGINAL ATROCITIES

Tasmania has a bloody colonial history, even by Australian standards.

It’s the site of some of the worst of the many massacres of Australia’s Indigenous people, where colonial authorities celebrated banishing the island’s Indigenous population through what Tasmanian historian James Boyce described as either “force or trickery”.

Their languages are now considered lost as well.

Remains of those Aboriginals including bones and skulls, some of which were exhumed from their burial sites on islands they were exiled to, were sent back to Britain, where they were put on display and studied in the then emerging field of phrenology, now considered a pseudoscience.

By the time the “last Tasmanian Aboriginal man” William Lanne died in 1869, public perception of the practice had shifted to the point the government promised a respectful burial, but according to Mr Boyce that didn’t happen and his skull “was stolen from the hospital on the initiative of the prominent doctor William Crowther, who later became Tasmania’s premier”.

At the time The Mercury newspaper lamented that “the common people have a better appreciation of decency and propriety than such of the so called upper classes of education”.

When Tasmanian Aboriginal woman Truganini died seven years later she was secretly buried behind the walls of a former jail, potentially in a bid to protect her from graverobbers, until her remains were exhumed two years later and moved to the Tasmanian Museum, where her skull was on show for more than four decades.

London’s Royal College of Surgeons discovered their collections held fragments of her skin and hair in 2002.

Last month the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) announced it would be trying to right some of the past wrongs.

The chair of the board of trustees at TMAG Brett Torossi last month said the board was “truly and completely sorry” for the “pain, suffering and ongoing trauma” inflicted on the Aboriginal people and said the board “offer and hope that this apology will be received in the spirit that it is given”.

“We give it unreservedly without asking for anything. We know and mourn that it is so belated,” Ms Torossi said, acknowledging the apology might not be accepted or could even be outright rejected by Tasmanian Aboriginal people given it “requires trust where there has been none”.

Ms Torossi also said the board “acknowledge their sovereignties in land and sea” was “never ceded”.

TMAG is now working to return the Preminghana Petroglyphs to the parts of far north west Tasmania where they were removed last century, as the state’s Aboriginal Affairs Minister Roger Jaensch announced last November.

The irony of that apology and announcement being followed by the news that one of the state’s biggest cultural attractions was looking to harvest the blood of Indigenous people for a cultural curio wasn’t lost on some commenters on Dark Mofo’s post.